Earlier this month, I was pulled into a conversation among the Wharton School students about the usual things: recruiting, technicals, financial modeling, Superdays. I was intrigued; I always enjoy getting a glimpse into what feels like another world, a world where the dollar is king. We got to talking about a well known guest column from a few months ago about land acknowledgements. One of the students who had heard about the article — but presumably hadn’t read it — began asking me questions as if I was ChatGPT. “What was the article? What is a land acknowledgement? Does Penn do those? What’s the issue?” While I appreciated the curiosity, I was shocked by the student’s unfamiliarity with the concept of land acknowledgements and the term “stolen land.”

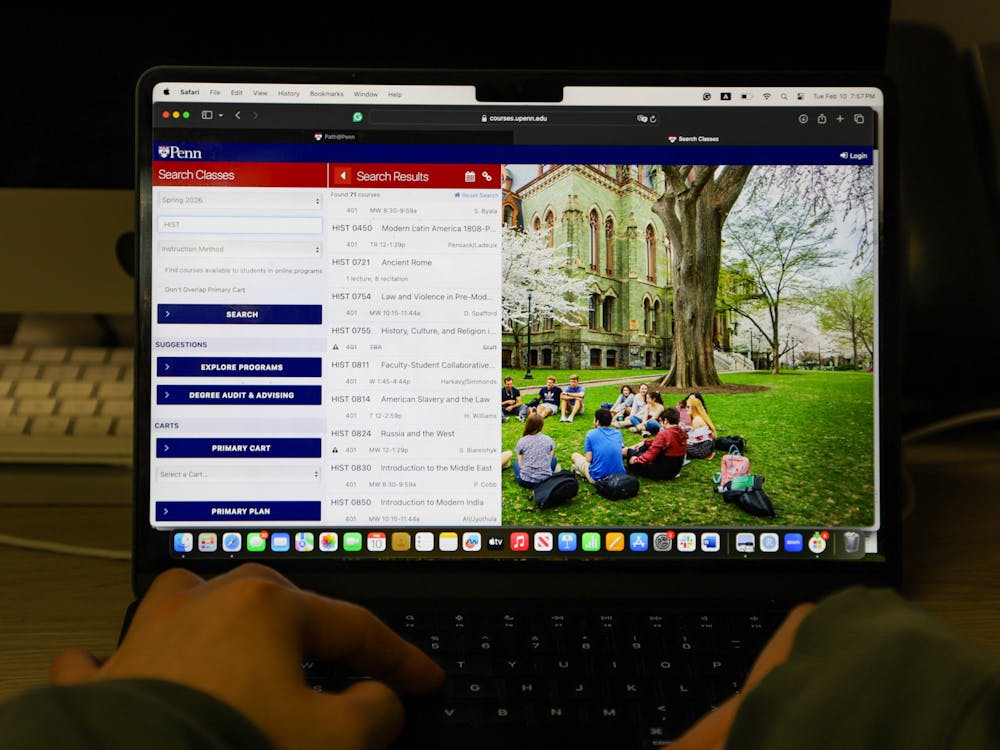

It then dawned on me to ask these interview-obsessed Wharton warriors, “have you taken a history class here?” The reply I got was disheartening but not completely unexpected. “No,” all of them responded with a giggle. “This is the first semester where I really have to write anything.” As a history major, I was horrified. While not everyone has had access to a learning environment where history was taught properly and fully, Penn students now do. In fact, many students’ lack of a strong history education in high school lends itself to the point I hope to make: you need to take a history class at Penn.

On the wall by the Starbucks in the Penn Bookstore is a quote by Benjamin Franklin, “Either write things worth reading, or do things worth writing.” As the discipline of history will show you, knowledge and the ability to think critically are the most powerful things we have as humans. For example, the institutionalized discrimination and subjugation of Black people in this country relied on the deliberate withholding of knowledge, primarily reading and writing, to uphold the economic system and ultimately, class supremacy. Lacking these things makes you highly susceptible to being controlled.

Now, it would be unfair to say Wharton students don’t take history classes. They do, and there are a number of humanities requirements needed for them to graduate. I know this because when professors routinely ask students’ reasons for taking courses on the first day, many explain that it fulfills a requirement. Still, that doesn’t mean they are getting the most out of those courses.

In one history class I took, I noticed a lot of Wharton students enrolling throughout the add period. Curious, I decided to actually look at the Penn Course Review rating for the course: it had a 1.4 out of 4 difficulty rating. Everything added up: this class was supposedly easy, the teacher was nice, and it checked a box in the Liberal Arts and Sciences general education requirement. Yet still, I heard my classmates complaining that they were struggling to write and admitting that they had asked ChatGPT to do simple assignments for the class. This is a theme I’ve begun to uncover, perhaps best illustrated by a conversation I had with a STEM major who told me they believed writing was nothing more than a “means to an end.”

This pattern at Penn follows a global trend that has come with the rise of artificial intelligence: the fall of intellectualism and critical thinking. As students, we must reevaluate our relationship with learning. Every class you take, whether it’s history, business, or biology, is meant to provide you with a different lens with which to view the world. Learning for the sake of learning and taking on your education with the understanding that knowledge is power — cheesey, I know — is why you came to this institution. So, while it is important for chemistry majors to memorize the periodic table and for Wharton folks to practice their technicals, the importance of reading, writing, and critical thinking should not be overlooked.

History and other humanities classes are where I actively sharpen my critical thinking skills, expand my knowledge, and apply what I've learned to the world around me. These classes have taught me to be skeptical, always questioning, and constantly looking for ways to dive deeper. It is about developing the skills necessary to think critically about the world and your place in it.

Regardless of your discipline, there is real value in being a strong writer and critical thinker. Meeting the bureaucratic requirements of the institution in order to earn the degree is necessary, but not sufficient for getting a well-rounded education. Yes, it is possible to graduate from a world-class institution without having gained a world-class education. It is up to you to make sure you are getting the most out of what Penn offers.

In many ways, this article might be preaching to the choir. I don’t expect those I’m speaking to will read it — I mean, they did tell me they don’t read the The Daily Pennsylvanian. Despite this, I hope whoever reads this encourages their peers or students to expand their knowledge base and actively question, interpret, and form sound conclusions about the world without the help of AI. If not by taking a proper class, by reading the news — past what's going on with the economy or the stock market, but what is happening to people.

The less you know, the easier you are to control, the easier you are to replace. The less we know about the past, the less we are able to recognize when we are the pawn in someone else’s scheme, and the easier it is for atrocities to repeat themselves.

MARIE DILLARD is a College sophomore studying history and urban studies from Englewood, N.J. Her email is mdilla@sas.upenn.edu.