A few weeks ago, on a Megabus back to Philly, a group of women noticed the Penn logo on my sweatshirt. Immediately after seeing where I attended school, one woman made a comment about how I must be rich. At first, I was surprised and a little hurt by her insensitive assumption about my background. But at the same time I knew that it was not unwarranted. She was justified in assuming my privileges as a Penn student.

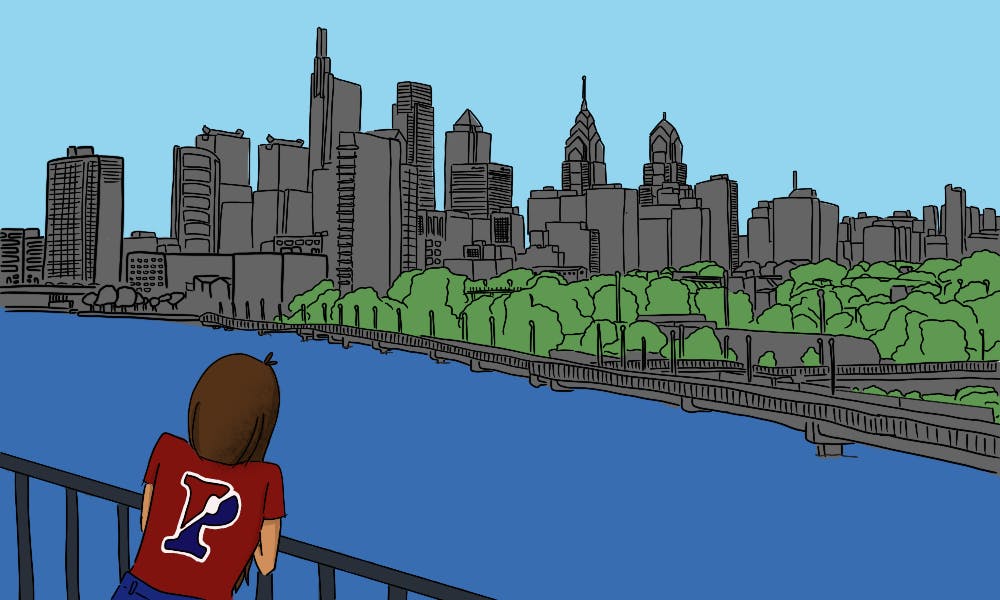

There is no denying that many Penn students come from wealthy families. According to the New York Times, 71% of Penn students come from the top 20% and 19% of students come from the top 1%, while only around 3% of Penn students come from the bottom 20 percent. Meanwhile, Philadelphia is the poorest of America’s ten most populous cities, and around a quarter of its population lives in poverty.

I will be the first to admit the immense joy and pride I felt upon opening my acceptance to the University of Pennsylvania. As a first-generation immigrant, it seemed as though my acceptance symbolized attainment of the elusive "American Dream." However, since taking on the role as a student here, my beaming pride for Penn has dimmed. The more I’ve learned about Penn’s influence and lack of reparations to the West Philadelphia community, the more I've begun to question whether my pride in this institution is justifiable.

If you are like me, and are not a Philadelphia native, your identity as a Penn student will be your primary role in the context of the city. Therefore, we must think deeper about the significance of how our role precipitates into the culture of the campus’ surrounding neighborhoods.

West Philadelphia public schools, located in Penn’s own backyard, see incredibly low test scores as a result of low funding and access to adequate resources. According to a US News Report, 0% of West Philadelphia High School students were able to pass at least one AP exam. As a result, many residents assume that a school like Penn is beyond their reach, even while they grow up next to its campus.

It’s a sad reality that while Penn finds its home in West Philadelphia, West Philadelphia residents do not see a home in Penn. Penn represents elitism and wealth. Many residents, like the woman who saw me on the Megabus, immediately associate Penn students with money. This perception gets extremely uncomfortable in the context of Philadelphia’s high poverty rates.

As we saw clearly in the latest admissions scandal, the American education system is designed to work against the poor, whether explicitly or implicitly. For many Philadelphia residents who struggle to get by, Penn is a full view reminder of a system that isn’t designed for them.

SEE MORE FROM UROOBA ABID:

While Penn claims its students engage with the local community, these actions are simply not enough. At the end of the day, what West Philadelphia deserves is adequate funding for its public education system. No ABCS course or Penn community engagement program will sufficiently replace the structural resources this funding can provide. And yet Penn, the largest private landowner in Philadelphia, is legally not required by law to pay property taxes — taxes which would go towards the public schools.

In addition, as recent protests call out, Penn is one of the only Ivy League institutions that does not make payments in lieu of taxes, or PILOTs, which could significantly help support the severely underfunded West Philadelphia public schools. The administration has argued in the past that their dismissal of PILOTs is due to their other contributions to the West Philadelphia community — such as the Penn Alexander school.

However, even this action had negative impacts on the local community. While the Penn Alexander school began as an effort to increase educational opportunity for the local community, the school has transformed the real estate in the area, making it difficult for low-income populations to continue living near the school. Since this displacement, the percentage of African American students attending the school has significantly dropped, along with the number of socioeconomically disadvantaged students.

These facts tell the story of Penn’s gentrification and the harm it causes to low-income families. When we criticize things like the recent admissions scandal, and acknowledge that people with money need to be held accountable, we should replicate that logic to institutions like Penn too.

When I wear Penn’s logo, I am representing an institution that has turned its back on its neighbors. As Penn students, we have a responsibility to think critically about the role of Penn in Philadelphia along with its role in the greater system of socioeconomic and racial exclusion. If we are going to go around Philadelphia wearing Penn’s logo with pride, we should at least recognize the troubled history the logo symbolizes.

UROOBA ABID is a College sophomore from Long Island, N.Y. studying International Relations. Her email address is uabid@sas.upenn.edu.