From being told they’re not a “good fit” to being pressured into dropping courses, Black students at Penn, inspired by the country’s racial reckoning, took to social media this past summer to allege patterns of racial discrimination and exclusion against the Chemistry Department.

The stories reflect the experiences of hundreds of Black students from across the Ivy League and were posted on Black Ivy Stories, a viral Instagram account dedicated to recounting such experiences that launched this summer.

Of the over 350 posts made since June 15, 60 are said to be written by Penn affiliates, comprising current students, former students, faculty, staff, and local community members. Eleven of these Penn-related posts detail experiences of racial discrimination within the STEM field by professors and other students.

Multiple posts levy accusations against Penn’s Chemistry Department, specifically alleging a pattern of behavior that alienated Black students and discouraged them from taking chemistry courses. The Chemistry Department has since apologized to certain students for their "negative experiences" related to the department, but the University as a whole has taken no such steps.

"Campuses are not immune from the bias and discrimination that occurs in broader society," University spokesperson Stephen MacCarthy wrote to The Daily Pennsylvanian. "Penn has and will continue to respond to concerns raised with campus resource offices and to create the type of campus environment that allows people from diverse backgrounds and perspectives to learn from and with one another."

Black Ivy Stories’ origin

Since its first post, the page has gained over 22,000 followers and posted over 350 submissions recounting experiences of racial discrimination and anti-Black bias within each school in the Ivy League. Submissions — which are only identified by school and affiliation to the Ivy League institution — are accepted from Black Ivy League students, alumni, parents, staff, and faculty, as well as other Black community members who have been impacted by racial bias.

Black Ivy Stories’ founder — who requested anonymity to protect the identity of the Instagram account — said they drew inspiration from Black Mainline Speaks, an Instagram page on which Black community members share their experiences with racism at schools on Philadelphia’s Main Line, a region of wealthy suburbs.

RELATED:

‘Designed to subordinate’: Experts talk racism in United States penal system at Penn event

Weingarten counselor and Penn grad reflects on race, religion in upcoming book of poetry

The founder believes that some students choose to submit to Black Ivy Stories instead of filing an official report with their university to make sure their voices are heard, alluding to the fact that even after filing an official complaint, there is a possibility that action will not be taken.

“I saw how much momentum [Black Mainline Speaks] is gaining, and how they’re holding these schools responsible for the actions of their students,” the founder said. “Students [and universities' administration] need to be held accountable at Ivy Leagues, as well.”

Black Ivy Stories on Penn’s Chemistry Department

On June 29, 2020, a post recounted a 2018 graduate's experience with an unnamed chemistry professor during office hours. The student, who was in their first year at the time, alleges that the professor implied that participation in sports is the only way the student would have gotten into Penn. The professor also suggested that the student drop out of an introductory chemistry and take chemistry courses at other universities in Philadelphia, as the course was not “a good fit.”

This was the beginning of a series of interactions with the professor that negatively impacted the student and their time at Penn, according to the post.

“The hardest part was being a [first year] who was still learning how to navigate Penn; I didn’t know who to report him to or how to deal with it after,” the post read. “I dealt with it myself.”

Another post, published on July 7, detailed the experience of a 2016 graduate, whom, after receiving a low score on a chemistry exam following the death of an acquaintance, the professor told to drop the course. After steadily improving on the following midterms, the student received a D as their final grade in the class. Months later — and after developing “crippling test anxiety and depression” as a result of the experience — the student asked to see their final exam grade. The professor then revealed he had given the student the incorrect final grade and that they had actually received an A- in the class.

In response to the post published on July 7 and other posts on the page referencing the department, the Penn Chemistry Department Instagram commented on the post, apologizing to the former student.

“On behalf of Penn Chemistry, we would like to extend our apologies for the multiple negative experiences you endured at Penn and in our department,” the comment read.

The comment also invited individuals to report incidents to the department's anonymous reporting form.

In an emailed statement sent to the DP on Aug. 5, Chemistry Department Undergraduate Chair Jeffrey Winkler wrote that the department was aware of the allegations and is taking steps to make the department more inclusive.

“The Chemistry [Department] is deeply committed to the success of all our students,” Winkler wrote. “While it is disturbing to hear that some students have had negative experiences in the past, the department is dedicated to learning from these past experiences and to providing a positive experience for all students moving forward.”

Winkler pointed to implicit bias and sexual harassment training that was mandated for all Chemistry faculty and staff in 2018, as well as an open-door policy in the department for Black students to air their grievances, as actions the Chemistry Department is taking to address the needs of students. Winkler also referenced newly established student and faculty committees on diversity, equity, and inclusion.

The anonymous students in the Black Ivy Stories posts were not the only students with negative experiences in Penn’s Chemistry Department and other STEM courses.

While Engineering sophomore Josh Bradford has enjoyed his courses in the Chemical Engineering program, he also pointed to experiences of racial discrimination with the Chemistry Department.

“A lot of [Black students] have been turned away from the Chemistry Department,” Bradford said. “I have friends who are pre-med, and they also have very horrible reviews of the department, so they’ve steered clear of chemistry majors.”

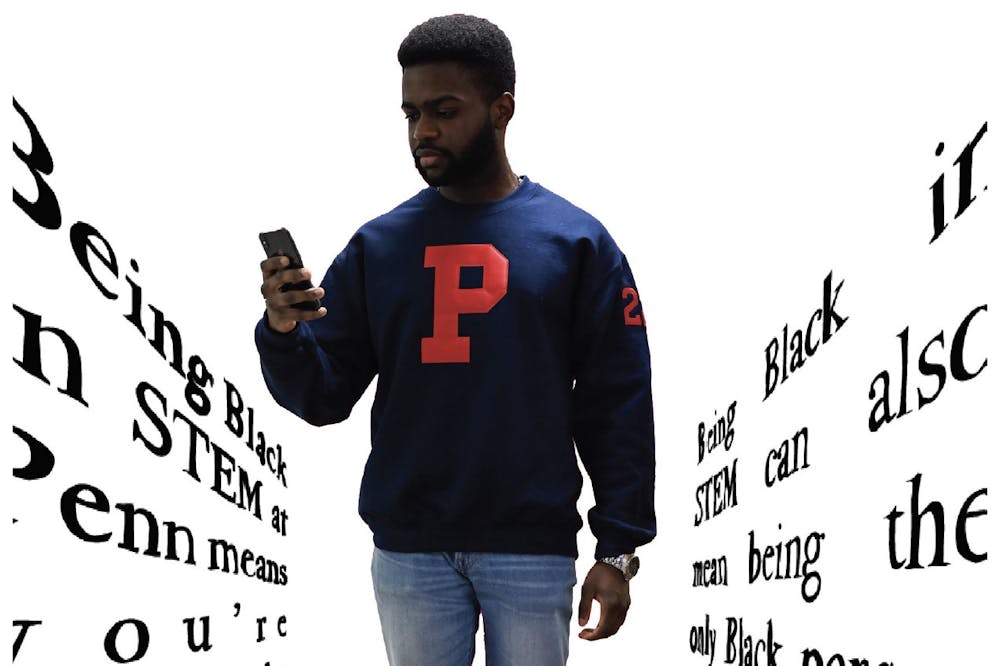

Bradford said he has felt the need to establish himself as a Black student worthy of taking STEM courses like the advanced chemistry courses required for his major, as the courses are largely composed of white and Asian students.

“Some of your peers will look at you like, ‘Why are you here?’” Bradford said. “And you have to realize, I am fully deserving of being here. I earned my acceptance here just as much as you did.”

Bradford said he has found that this feeling of not belonging or being unable to handle the course material continuously prompts Black students to leave STEM majors and courses.

“I have had friends who have transferred from STEM disciplines to non-STEM disciplines because of that,” Bradford said. “And I’ve [known] people who were discouraged to follow their pre-health careers just because they felt like they weren’t capable of handling the material anymore.”

He also said that if there were more Black professors teaching STEM courses, he believes Black students might feel more comfortable taking these courses.

“I feel like Black professors tend to do a better job of understanding racial biases and be, like, look, there are people here who come from completely different backgrounds and don’t have the same resources as some of their classmates,” Bradford said.

Changes being made within Penn’s Chemistry Department and STEM programs

Upon hearing of the allegations against the Chemistry Department on Black Ivy Stories, Roy and Diana Vagelos Professor in Chemistry and Chemical Biology and Chemistry Department Chair David Christianson told the DP in an interview on Feb. 24 that he was ashamed about what was being said about the department.

In June 2020, shortly after the posts appeared on Black Ivy Stories, the Chemistry Department formed a Committee on Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion.

The DEI Committee was formed to promote "an anti-racist/anti-discriminatory culture within the Chemistry Department," according to its mission statement. There are currently 14 committee members, including faculty, staff, graduate students, and postdoctoral students.

While the DEI Committee has implemented a mission statement, the "responsibilities" and "initiatives" sections on its website remain empty. Chemistry professor and Chair of the DEI Committee Elizabeth Rhoades told the DP on Feb. 26 that committee members are currently surveying department attitudes about diversity and inclusion in order to identify the most pertinent issues for the committee to address.

“We want to make sure the information we put up is actually what we’re doing and reflects our efforts to make meaningful change,” Rhoades said.

She said DEI Committee has needed time to develop proposals, especially while working virtually, but one of the most recent initiatives is a presentation on equity and inclusion in STEM by representatives from Amherst College that took place on Feb. 24.

Amherst began the initiative Being Human in STEM — which aims to create an inclusive and equitable environment in STEM — in 2015 after Amherst students conducted a sit-in to discuss the experiences of marginalized students on campus.

Rhoades said the DEI Committee has similar actions planned for the near future, including another Amherst-led workshop in collaboration with Penn’s Center for Teaching and Learning on how to create an equitable classroom environment. Next year, the department is hoping to implement a program that allows first-year students interested in chemistry to join research labs, Rhoades said.

Christianson said he has been trying to change the culture of the Chemistry Department ever since he was appointed department chair in 2018. He said the culture of the department "was not evil,” but there was a general lack of awareness about diversity and inclusion when he first took over.

Christianson said that, in particular, he has been trying to discourage faculty from making hurtful comments to students.

“I have cautioned faculty more than once about the danger of snarky comments, because someone might take it the wrong way,” Christianson said. “I think half the problem is getting people to think before they talk.”

He said that upon becoming department chair, he modified the structure of department meetings — which are annual and open to all students, faculty, and staff in the department — to address diversity and inclusion, as opposed to just focusing on lab safety, as they had in the past.

“I explained to the department that safety is more than just wearing safety glasses; lab safety is dignity and respect for all persons,” Christianson said.

He said department meetings have also featured presentations from University officials on topics ranging from unconscious bias to sexual harassment and Title IX. Christianson said he believes the presentations have been impactful on faculty, citing a 2018 training by LGBT Center Director Erin Cross on gender inclusivity when some faculty members expressed interest in learning about more inclusive terminology after the department meeting.

Gabriel Angrand graduated from the College in 2017 with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry. Since 2019, Angrand, a learning instructor with the Weingarten Learning Resources Center, has been working with the Chemistry Department to create a supportive learning environment for underrepresented students.

Angrand met with the department in February 2020, months before the inception of Black Ivy Stories, to discuss how the department could support all undergraduate students, regardless of their background. The conversation gradually shifted to the needs of underrepresented students after he and another Penn graduate advocated for them, he said.

When Angrand met with department faculty again in July 2020, he said faculty members were aware of the allegations from the Black Ivy Stories page.

While Angrand said the allegations were never directly discussed, they helped underscore issues that the department had already been working to address, including how to help underrepresented students succeed in science and how the department can increase inclusivity within its courses.

As an undergraduate student, Angrand had a more positive experience in the Chemistry Department compared to other Black students. After failing an exam during his first year, Angrand’s professor directed him to Weingarten, where he found a student who helped him understand the material. He said that it was his positive experience in the department that motivated to meet regularly with the department and help undergraduate students.

“I find it honestly heart-wrenching that so many students have bad experiences with chemistry,” Angrand said. “Not just with the content, but with the instructional team sometimes.”

Angrand believes that professors can create a more inclusive environment by interacting with students on an interpersonal level. Techniques range from asking students questions prior to the beginning of the course about their feelings on the subject, to pronouncing students’ names correctly, he added.

He said he has noticed that, even if professors are interested in helping their students, many are far more focused on producing research than creating an inclusive classroom environment.

“I think one of the institutional issues is that professorship is not as much connected to your craft as an educator as it is to your ability to produce research,” Angrand said. “I think that’s one of the big issues that contributes to a number of professors maybe not actively discouraging students, but also not providing students the resources they can tap into.”

In an emailed statement to the DP on Feb. 28, Chemistry professor Zahra Fakhraai wrote that, in her experience, many of her colleagues are invested in educating students, but faculty members can have limited resources or other factors in their life that affect how much time they can commit to teaching.

“Many of our faculty with young children have had to balance child care and child education with both research and education,” Fakhraai wrote. “Faculty, too, can be neurodivergent or have disabilities that can affect how they manage time and how much time they can commit.”

Fakhraai wrote that she has attempted to create an inclusive classroom environment for her own students based on training from the Center for Teaching and Learning, including emphasizing the importance of learning over grades, meeting with students, and creating surveys to get to know them better. Fakhraai has also tried to empower students through group work, and wrote that she is conscious of how often underrepresented students can face microaggressions from their peers.

“As a teacher, it is then critical for me to provide opportunities for these students to form study groups that are conducive to their learning, make sure they are included in existing structures, make sure they find resources that can help them, and make sure the rest of the class has an understanding that their behavior can result in exclusion,” Fakhraai wrote.

The Chemistry Department is not the only STEM field attempting to address struggles faced by Black students. Last July, Penn’s chapter of the National Society of Black Engineers facilitated a conversation on racial bias experienced by students and alumni. A survey of Black Engineering alumni from 2013 to 2019 found a pattern of discriminatory treatment on the basis of race, wherein 55% of alumni felt excluded from the Engineering Department, while 70% of students felt that professors gave up on them too easily.

Fakhraai wrote that she believes that the Chemistry Department is making progress, citing the commitment by department leadership to creating an equitable learning environment and making sure faculty are aware of biases when interacting with students.

Still, Fakhraai believes there is room for improvement. She wrote that many graduate students and new faculty members have no training on inclusive teaching practices, and there is a lack of support on the institutional level for training students and faculty.

“We have lots of work to do to break the structural barriers and gatekeeping that keep underrepresented students away from chemistry,” Fakhraai wrote.

Rhoades said she is hopeful that the initiative by the School of Arts and Sciences to create a position for an associate dean for diversity and inclusion will provide more resources to departments for supporting equity initiatives, including potentially creating a departmental position that exclusively focuses on diversity and inclusion.

“I think having a faculty-led committee is hopefully just a stepping stone,” Rhodes said. “I’m hoping we can create some inroads with this committee that will convince the University to help us get more resources and support our efforts.”

Christianson said he believes the Chemistry Department is improving, but it is still far from where it needs to be.

“At least compared to where we were when I became chair in 2018, we’re in a better place now,” Christianson said. “I just wish the transition would be more rapid.”

Despite alienating experiences of anti-Black racism and discrimination by faculty and students, Bradford believes that Black students should not be discouraged from STEM. If Black students continue to leave the field, efforts to make STEM more inclusive would be harmed, Bradford said.

“In order for us to see change, we have to stick through it,” Bradford said. “I think the lessons we learn are rewarding because I feel like this is also reflective of society as a whole.”