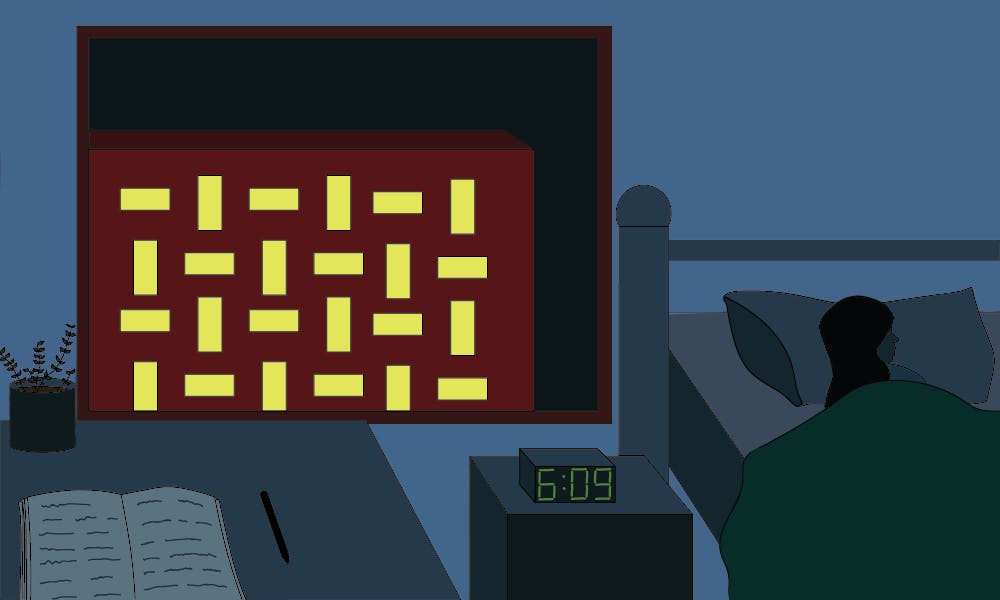

On nights when I can’t fall asleep, I’ll lay on my side and look out my window. I have a panoramic view of University City, but right in front of me is the west face of Hill College House and its obliquely shaped windows. It surprises me how even at 4 or 5 a.m., a considerable number of windows are brightly lit.

Everywhere you go, people are talking about sleep. “I slept for only four hours last night.” “That’s not even bad. I only got two hours.” “You guys are complaining about nothing. I got no sleep last night.”

It’s like a competition: whoever sleeps the least wins. Functioning with little to no sleep is like a badge of honor for them, a display of invincibility.

As someone who deals with sleep anxiety and moderate insomnia, I’m not impressed. I’m not saying that I’m a stranger to occasional all-nighters, but I do put in great effort in trying to maximize my sleep. Many nights, I end up tossing and turning until the morning. So, the fact that my peers, most of whom are physically capable of gaining a good night’s sleep, are getting minimal sleep and are boasting about it not only concerns, but aggravates me.

These students truly embody the “sleep is for the weak” mantra. As a whole, the general consensus on sleep seems to be that it’s simply available to us, and we can let it dwindle. In fact, Penn has previously ranked second among colleges with the latest bedtimes. Penn has recognized the need for change through a number of acts. Closing Huntsman early and starting the Refresh program, a seven-week online program that allows students to monitor their sleep patterns are good efforts. But, additional action is required to effect a major shift in students’ perceptions of sleep.

This past summer, for the Class of 2022, Harvard University implemented Sleep 101, an “interactive module designed to increase student awareness of the health and performance implications of sleep.” A 45-minute course, Sleep 101 features talks from sleep advocate Arianna Huffington and practical tips and strategies on optimizing sleep. As part of the wellness fair, “Happy Healthy Harvard,” sleep aids, such as eyemasks and ear plugs, were distributed to students. Harvard has set new goals of training proctors, tutors, and mental health liaisons in sleep cognizance.

According to Harvard, the preliminary results of Sleep 101 are promising. A 2017 study found students were “less likely to drive drowsy and pull ‘all-nighters’” after completing the course. For some, Sleep 101 has ended up as the target of many sleep-related jokes and memes. For many others, the course has helped in shifting overall attitudes towards sleep. Seeing the administration so willing to invest in changing students’ sleep habits is encouraging. The open discussion that’s attached to Sleep 101 helps develop a sleep-friendly environment.

SEE MORE FROM CHRISTY QIU:

Partying can be fun for some, but an overwhelming mess of booze and sweat for others

When picking the next batch of Quakers, focus on merit, not legacy

Offering courses on sleep can add to this open discussion and further portray faculty’s recognition of sleep issues around campus. One such course is “Time for Sleep: Impact of Sleep Deficiency and Circadian Disruption in our 24/7 Culture,” a freshman seminar at Harvard. Since this fall, Yale has started offering a similar seminar, “The Mystery of Sleep.” Stanford University established the world’s first undergraduate sleep science course, “Sleep and Dreams,” covering topics like dreams and sleep disorders. More importantly, it “empowers students to make educated decisions concerning sleep and alertness for the rest of their lives and shapes students' attitudes about the importance of sleep.”

Courses like these are immensely popular among undergraduates, but at Penn, they have yet to be introduced.

The importance of sleep has never been underscored in my classes. I have yet to receive a, “Rest up!” or “Remember to catch up on sleep!” from my professors. In one class, my professor asked how we perceived a certain female character in a scene where she laid restless in bed. One of my classmates responded with “pathetic,” and my professor along with some other classmates nodded in unison. I felt a pang of self-pity, as if my own sleep issues were being belittled. The class has since moved on to other pieces of literature, but “pathetic” echoes vividly in my memory. Issues surrounding sleep should instead be handled with care and compassion.

When the administration shows that it’s taking action on an issue, students can more easily understand the full scope of a problem and take action themselves. They know the physical and mental effects of sleep — it’s in the back of their heads. An extra push toward sleep empowerment can begin a dynamic wave of altering attitudes. Hopefully, in the future, when a new resident occupies my room, awake at 4 a.m. and looking out the window, the obliquely shaped windows of Hill aren’t brightly lit, but comfortingly dark.

CHRISTY QIU is a College freshman from Arcadia, Calif. studying architecture. Her email address is christyq@sas.upenn.edu.