The forefront of Civil War medicine was located right in Penn’s backyard.

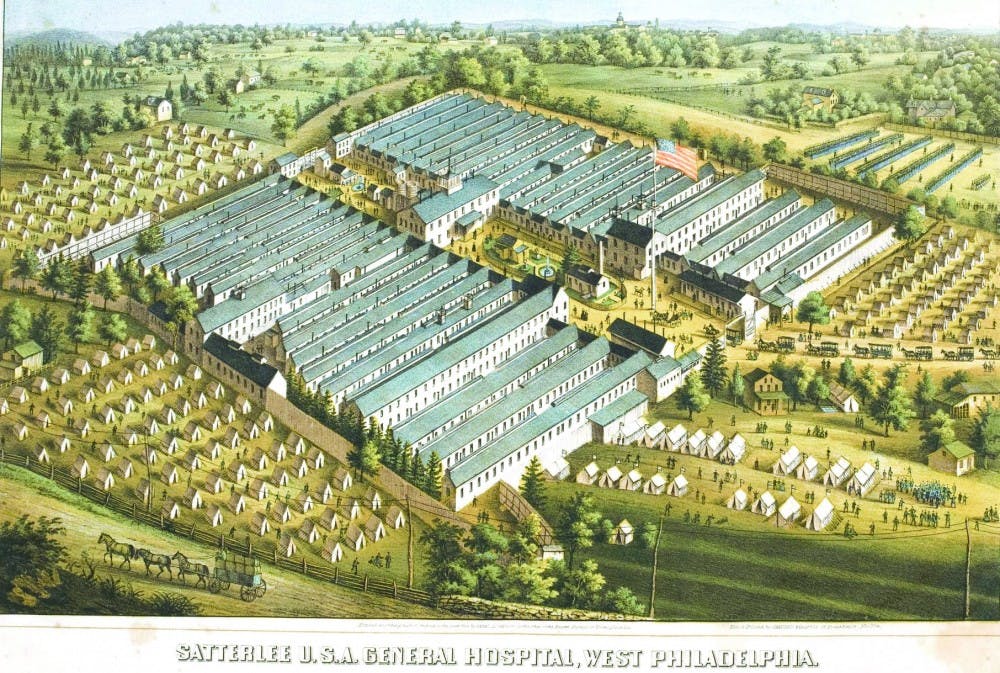

When it opened in 1862 — while the University was still at 9th and Chestnut streets — Satterlee Hospital had a total of 3,124 beds and open areas that could be tented outside to hold another 900 patients. The hospital stretched from approximately 42nd and Baltimore streets to 45th and Pine streets, which includes a portion of what is now Clark Park.

While a memorial currently stands at Clark Park, the two separate times that University City Historical Society purchased steel highway signs to put along Baltimore Avenue, the signs were stolen.

“It was a shame,” Michael Hardy, the former president of the UCHS, said, “because we really wanted to have another permanent marker of what once was here in University City.”

Hardy said that Satterlee is one example of “this area of the city being developed not just for residents,” but for helpful civic institutions like hospitals and orphanages.

In charge of the hospital was 1853 Penn Med graduate Isaac Hayes. Before he was appointed the director — or surgeon-in-charge — of the new hospital, Hayes had gone on two expeditions to explore the Arctic. By the time he had returned home, however, the nation had turned its attention to war.

Surgeon General William Hammond decided that Hayes needed a position even higher than Brigade Surgeon, which President Abraham Lincoln had personally recommended him for, and ordered Hayes to report to West Philadelphia to oversee construction of the hospital immediately.

“He had the fortitude to survive two Arctic expeditions and on top of that, he had the medical knowledge from his Penn education,” Adam Clements, a 2012 recipient of a Master’s in Public History from La Salle University, said.

Related

MULTIMEDIA: Civil War history at Penn

2/27/2013: Going undercover to ‘recover the priceless’

Duke University history professor Margaret Humphreys became interested in Satterlee as part of a larger book on Civil War medicine after reading copies of the West Philadelphia Hospital Register.

By looking at Satterlee, she said, “We get a glimpse of the modern hospital to come.”

This demonstrated itself in ways like doctors’ hierarchical organization, with the more experienced supervising the less experienced, according to Humphreys.

In addition, Humphreys added, during the war, medical schools from Philadelphia like Penn and Thomas Jefferson University brought their students to see interesting cases.

Satterlee “represents one example in a massive learning experience for American doctors and venue for the spread of medical knowledge of its time,” Humphreys said.

Clements, who now volunteers at Woodlands Cemetery, said he first became interested in Satterlee when he was living in a house overlooking Clark Park. When an assignment came up as he pursued his master’s degree asking him to write about any Philadelphia historical site, he was drawn to the hospital.

“Satterlee was a grand experiment,” Clements said. “Nothing like it has even been attempted in American warfare.”

While originally the Union thought it would handily rout the Confederacy in the war, these dreams were dashed in July of 1861 at the First Battle of Bull Run, where the Confederate troops handed the Union a resounding victory.

That winter, a realization set in that this would be a bloody, protracted war. The U.S. Sanitary Commission, set up during the war, realized that commonplace makeshift hospitals would not fit the bill. It was decided larger, more official hospitals needed to be built.

One of these, originally known as the West Philadelphia U.S. Army Hospital, became Satterlee Hospital, named after Richard Sherwood Satterlee, a medical purveyor during the war.

Satterlee’s doors opened on June 9, 1862, even though the hospital had not yet finished construction. Wounded soldiers came from as far away as Virginia, typically transported by boat. In the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg, Satterlee admitted over 4,000 patients.

A great amount of effort went into keeping sufficient ventilation and avoiding diseases typically associated with Civil War hospitals. This, along with proper medical care of battlefield wounds, resulted in there being only 110 deaths from October of 1862 to 1863, despite over 6,000 patients being admitted to Satterlee. This rate is much lower than many of its peer hospitals.

Providing an invaluable service to Hayes was the Sisters of Charity, a group of nuns who made it their duty to help devastated communities. According to Clements, the nuns’ presence was requested by Hayes, who did not share the squeamishness of some at having women in such a ghastly atmosphere.

There was a great emphasis on patients’ literacy, with the West Philadelphia Hospital Register published weekly. It was often filled with stories — typically written by patients in the hospital — of adventures on the battlefield. Satterlee also boasted a sizable library with over 1,200 books and 1,300 magazines, with local women acting as librarians.

Satterlee Hospital officially closed its doors on August 3, 1865, several months after General Robert E. Lee and the Confederacy surrendered at Appomattox Court House, and the land was sold to a local development company.

The area turned residential, with many duplexes. “Land values were on the rise, and there no more need for a Civil War hospital,” Clements said.

“It was a very intense, very temporary settlement of human beings. There were all those people, all those supplies and everything else there, and then it was just gone,” Director of the University Archives and Records Center Mark Lloyd said.Seven years after Satterlee closed its doors, Penn moved west across the Schuylkill to its current home.

Related

MULTIMEDIA: Civil War history at Penn

2/27/2013: Going undercover to ‘recover the priceless’