Since their erection in 1969, the high rises have weathered generations of undergraduates and decades of rumors about demolition. Harrison College House’s renovations — which were completed this summer — prove that the high rises are here to stay.

Penn alumna Cheryl Brown, who lived in Harrison from 1982 to 1986, recalled that most students believed the high rises were temporary residences. At the time, they were not part of Penn’s college housing system and did not enjoy the popularity they do today.

According to University Archivist Mark Lloyd, before the high rises, the Quad and Hill College House were Penn’s only on-campus undergraduate residences. The entire architectural visage of the campus was starkly different. It was smaller — both in acreage and height — more traditional and much less interconnected.

In response to surges in student enrollment after World War II, the high rises — cradled within the superblock between 38th, 40th, Walnut and Spruce streets — were created to increase on-campus housing, aiming to “convert Penn from a university that was primarily commuter to primarily residential,” Lloyd said.

Given the decay of the Philadelphian economy at the time, building apartments for 2,400 beds was not a matter of scrounging for change under mattresses. The enterprise was costly and used funding from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Lloyd confirmed that it was not until 2008 that Penn gained complete ownership of the high rises.

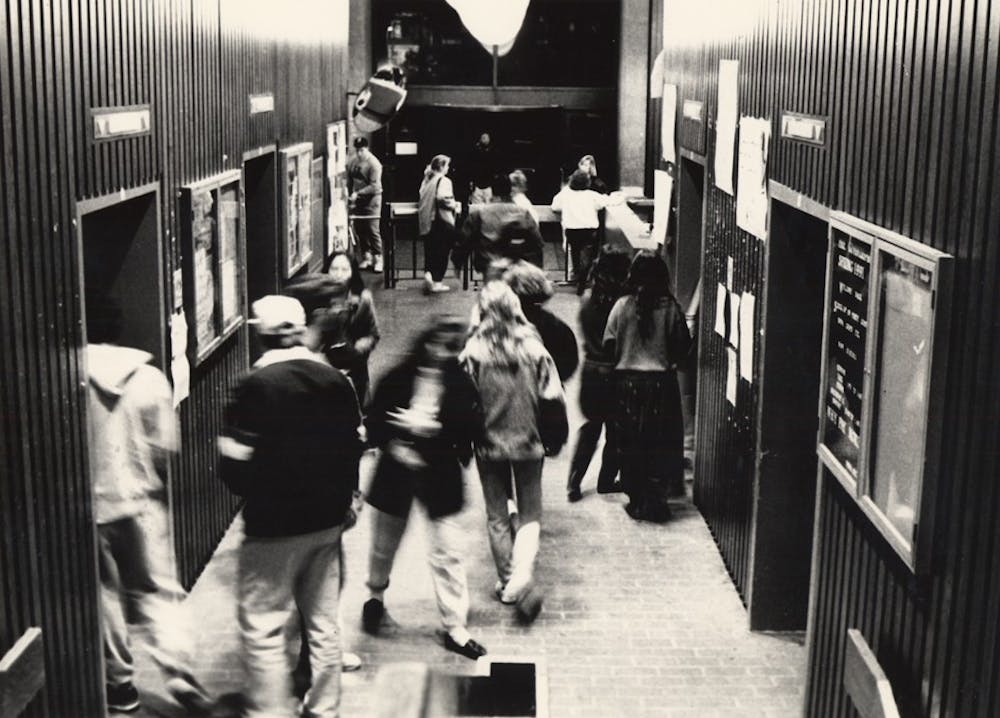

Living in the high rises

The first students moved in during the fall of 1970.

Lisa Rosenberger, a Penn alumna who lived in Harnwell College House from 1972 to 1974, said that she was happy about her living situation. The high rises provided an appreciated escape from dorm life and on-campus dining. Above all, she noted, it provided a safer alternative to off-campus housing in West Philadelphia.

“Our parents didn’t want us to live off campus. Back in those days, West Philadelphia was wilder than it is now — a lot more,” Rosenberger recalled, adding that Penn’s rapid expansion exacerbated local tensions.

David Brownlee, a History of Art professor at Penn and former director of College Houses and Academic Services, co-authored a book called Building America’s First University about Penn’s construction.

Sister Mary Ann Craig, a former neighborhood resident, said in Brownlee’s book that Penn’s expansion “not only depressed property values but also [created] a sense of disconnection from the responsibility to take root and seriously plan our lives together as neighbors.”According to the book, students also complained about a lack of community, which manifested itself in the high rises. The decline of the high rises’ popularity reached an all-time low in the 1990s, when “dormitories had so many vacancies that rooms were being rented to Drexel students,” according to the book.

Judith Rodin — then president of the University — responded by instituting a college-wide housing system in 1998, aiming to “move beyond the patchwork of college houses that existed at the time,” Lloyd said. Evidently, the superblock of the 1970s became a central piece of Penn’s fabric.

Renovating to Reintegrate

The first four years of the most recent renovations — which began in 2002 — targeted the building exteriors, repairing cement fissures while transforming aesthetics. Walls were repainted and the floor-to-ceiling windows were installed.

Just before completion of the projects in 2005, a series of pipe bursts left residents of Harnwell without access to hot water or electricity for several days.

Thus, renovating the interior systems of the high rises became “a priority of the campaign,” said Douglas Berger, executive director of Business Services. The six-year long, $100 million project — funded mostly by donors — upgraded mechanical and electrical systems, renovated flooring and furniture, new facilities and most noticeably, more efficient elevators.

“It was quite an accomplishment,” said Business Services spokeswoman Barbara Lea-Kruger, commenting on the cooperation and coordination necessary for the project.

“Each summer, we have to start as soon as [students] move out and finish before they come back … each part of the team had to know exactly what they were doing so that the team after them can build upon their finished products,” Lea-Kruger said.

At times, however, efficiency compromised accuracy. On one particular occasion, a student walked into his apartment and asked, “Where is my bathroom?” In their haste, the construction team had sealed off the doorway to his bathroom, Berger explained.

Looking Forward

This September, the renovation of Harrison’s last elevator checked off the final box on a long list of high-rise projects.

Looking ahead, Facilities and Real Estate Services is in the midst of planning for next summer’s renovations on Sansom East and discussing the possibility of a new college house on Hill Field.

Editor's Note: The article has been updated from its print version to reflect that Kings Court and English College Houses will not be renovated next summer.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

DonatePlease note All comments are eligible for publication in The Daily Pennsylvanian.