What length would you go to retrieve your father's stolen remains?

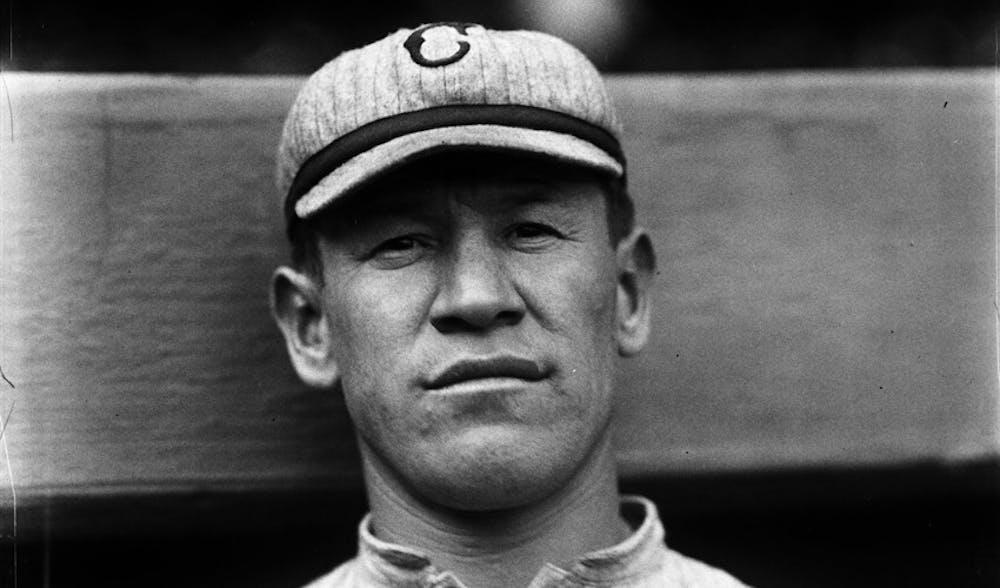

This Thursday, the Penn Museum will host the performance of "My Father's Bones," a play about the efforts of the sons of famous Olympic athlete Jim Thorpe to reclaim their father's body ever since it was sold to a museum in the 1950's.

Jim Thorpe had wanted his children to give him a proper burial according to the traditions of his Sac and Fox tribe, which involves four ceremonies and then a burial. In the middle of the fourth one, Thorpe's widow, who was not Native American, suddenly walked into the room with a state trooper and took her husband's coffin.

Play author Suzan Harjo said that Thorpe's widow "shopped his body around" before eventually selling it to a town in Pennsylvania, which made it into a highway attraction.

Despite legal battles that continue even to this day, Thorpe's sons have been unable to regain possession of their father's body and bury it in traditional Sac and Fox fashion.

Harjo is an internationally known advocate for Native American rights and was the 2014 recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom. She, along with other Native American advocates and curators from the Penn Museum, will speak in a panel discussion immediately following the production about steps Native American people have taken over the past few decades to prevent such stories.

One thing to be mentioned on the panel is the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. This bill requires conversation between the owners of stolen and exhumed Native American bodies and their families.

Though the NAGPRA could potentially take away attractions from museums, the Penn Museum was in support of its passage in 1990.

"We didn't focus on the punitive side, we focused on the policy side," Director of the Penn Cultural Heritage Center and panel speaker Richard Leventhal said.

This law is different insofar that instead of fining or taking disciplinary action against museums that own exhumed remains, the two sides must meet to discuss their own solution.

"It's going to work the way people decide it's going to work," Harjo said.

"The law has been flexible enough to allow for a lot of communication, discussion, and development," Leventhal said. He added the goal is not to punish, but to teach both each side about the goals of the other and allow for a peaceful, mutually beneficial agreement.

Related: Controversy about Alaskan Artifacts at Penn Museum