Sixty percent of the Quaker men’s fencing team come from just four states, and that isn’t just a coincidence.

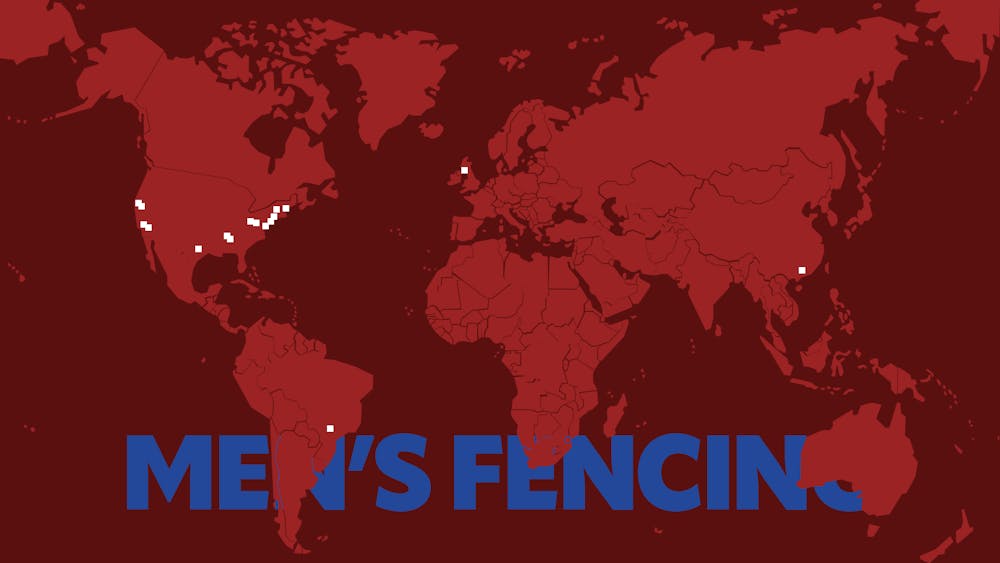

Most players on the team came to Penn from the most prestigious fencing clubs in their regions, and the 20-person squad features fencers from seven different states and four countries. As with their diverse backgrounds, many fencers had unique experiences as high school athletes.

Raymond Zhao, a junior from Atlanta, competed in Nellya Fencers Club throughout high school, which makes a shortlist of distinguished clubs in the United States.

“For the age groups between 1999 to 2001, [Nellya Fencers] churned out, for boys and girls, around 12 out of the top 15 fencers in the country,” Zhao said.

When Zhao was still an aspiring collegiate fencer, Nellya Fencers was the best option among an already limited selection. Outside of California and New York City — which each host several top-tier clubs — those looking to fence at a higher level naturally look toward the top club in their area.

USA Fencing only has around 40,000 registered members, and the sport becomes quite costly at a competitive level, which limits potential expansion. To stand out as a high school fencer, excelling within high school athletics is not enough. Joining a club is almost a necessity, and dues are expensive, with equipment and travel fees proving the same story.

With higher than normal barriers to entry, USA Fencing is already at a disadvantage to maximize youth potential. But another threat to the sport's expansion has been that fencing culture is not always focused around a love for the sport. As a high school fencer, Zhao recognized that the desire to attend elite universities underpinned a lot of his clubmates' motivations.

“To be honest, it’s a cash grab for a lot of coaches. People are obsessed with the notion of getting into Ivies from fencing, and then [the coaches] use their athletes really promotionally sometimes,” Zhao said.

This was also understood and often even promoted by the coaches, who marketed their services as a means of both reaching top aspirations within fencing, but also for improving chances to get into prestigious colleges.

Bryce Louie, a sophomore from Los Angeles, had a contrasting experience with his top-tier club. He, along with freshman Eric Yu, attended Los Angeles International Fencing Center, which had four first team All-Americans for the 2019-20 fencing season. But he didn’t view his experience as transactional or superficial to any degree.

“My fencing coach is my second father, and I’ve traveled the world with him. I would take a bullet for him — I love him that much,” Louie said. “Through our camps and training sessions we developed a relationship. My coach developed my character as a fencer and as a person.”

Louie lived in an urban, less affluent part of central Los Angeles, which was certainly an anomaly among most of his peers in the sport. He had to consistently commute upward of an hour to attend his training sessions. And it proved a rather unique experience for top fencers from New York City and California, who have the liberty of multiple clubs to choose from.

While the United States has a distinct, affluent fencing culture, most parts of Europe and the rest of the world are exceedingly different. Finn McMullan, a freshman from Northern Ireland, pursued fencing through a vastly separate experience from many of his American peers. Living outside of Belfast in a small town called Comber, McMullan began his fencing journey because of a natural affinity for swords.

“I live in a rural sort of area, on an old farmhouse," McMullan said. "I used to swing sticks at what I pretended to be invisible bad guys when I was quite small — maybe five, six, seven years old. Eventually, I asked my mom if I could do something with swords, so she Googled around and came up with fencing.”

There was no prominent culture or true fencing community in Northern Ireland, and while many of his peers were having near-daily practices at their top-tier fencing clubs, McMullan would practice three or four times a week in a local school gym.

“My fencing club, on an average night, would have maybe six to seven fencers, plus one to two coaches,” McMullan said.

But this was quite the norm for European fencing, and, outside of a few larger fencing institutions scattered throughout the continent, many of McMullan's peers had similar experiences.

“There are a lot of nice facilities available in the U.S. and in Europe, I see less of them," McMullan said. "Some clubs definitely have them; I know Paris has a club or two with a lot of those types of facilities. However, I think overall, Europe doesn’t have the same resources as Americans have with regards to facilities.”

While the Penn men’s fencing team comes from a wide array of different perspectives and experiences, they have gathered in Philadelphia to compete as the Red and Blue. And by fighting as a team for each other every single day, they’re bonded by something far greater than their places of origin.