When Wharton professor Nina Strohminger asked undergraduate business students what they thought the average American worker’s salary was, her students had no idea their answers would be the subject of a viral conversation about privilege, income inequality, and elitism.

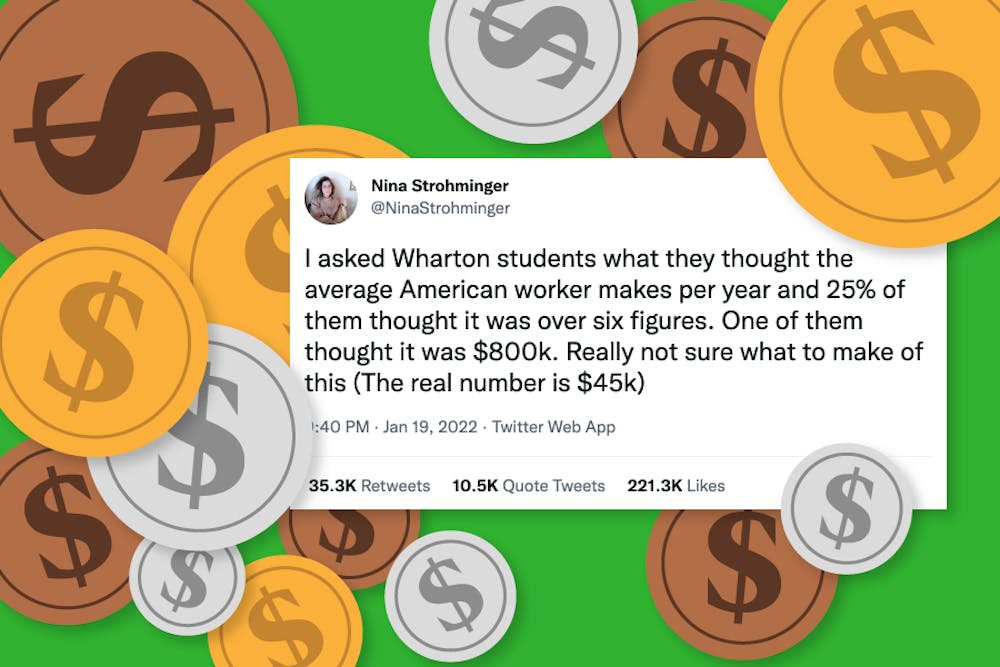

Strohminger polled students in her LGST 100: Ethics and Social Responsibility course, a required Wharton class for undergraduates, on Jan. 19. That evening, Strohminger posted on Twitter that she asked students what they thought the “average American worker" made per year, revealing that a quarter of students surveyed estimated over six figures.

Her tweet specifically mentioned that one student had posited that the average worker’s annual salary was $800,000 per year. The figure, however, is far lower: the average American worker only made $53,383 in 2020, according to the Social Security Administration, and the median annual salary that year was $34,612.

Overnight, Strohminger’s tweet garnered hundreds of thousands of likes and tens of thousands of retweets. LinkedIn published an article titled “Wharton students schooled by Twitter,” and MarketWatch's coverage spoke directly to Strohminger’s students: “No, Wharton students, the average U.S. worker does not make $800,000.”

One student, Wharton first-year Juan Lopez Ramos, a member of Strohminger’s course, however, claimed that the survey is not representative of Wharton students.

“She started class talking about how her tweet went viral and how the purpose was to show how people don't estimate [average income] correctly,” Lopez Ramos said. “But I think instead it showed how skewed income is for people who go to Wharton and Penn in general.”

Strohminger had sent a clarifying tweet the next morning, writing that the results from the survey were not unique to business students in Wharton.

“A lot of people want to conclude that this says something special about Wharton students — I’m not sure it does. People are notoriously bad at making this kind of estimate, thinking the gap between rich and poor is smaller than it is,” Strohminger tweeted on Jan. 20.

Respondents on Twitter also noted that at Penn, the median family income is much higher than the average across the U.S. The New York Times estimates that the median income of the family of a student who attends Penn is $195,500 per year — the third highest in the Ivy League behind Brown University and Dartmouth College. It also estimates that 71% of students at Penn come from the top 20% of households in America.

Lopez Ramos, who identifies as a first-generation and low-income student, said that the issue of income inequality is not unique to Wharton or Penn, and it is a problem across all elite universities in America.

“I feel like it carries everywhere, and it's not just a specific Penn thing,” he said. “I have friends at Yale [University] who say certain things that are very classist and elitist, but they don't really realize it because that's just how they grew up.”

Lopez Ramos also said that some students did not take the survey seriously which may have thrown off the results. He said that a student in the class had admitted to submitting the $800,000 figure as a joke, and another student admitted they had answered “$15 million.”

Strohminger did not respond to a request for comment.

College junior Laura Santos, who identifies as a FGLI student, said she was not surprised by the results of Strohminger’s survey.

“There’s no surprise that [Penn students are] out of touch with reality. People try to [say] ‘Oh, but this is an outlier,’” Santos said. “No, it's not. If you're low-income at Penn, you know that this is not an outlier.”

Less than half of undergraduate students at Penn receive any grant-based financial aid, according to Student Registration and Financial Services.

Santos said that she has received “insensitive” and “out of touch” comments from peers before about her financial situation. Santos, who said that she receives a generous financial aid package because she lost both her parents, remembered peers who told her she was “lucky” that her parents died.

Derek Nhieu, a junior in Wharton who also identifies as FGLI, said that he was concerned that Wharton students, who may go on to be business and political leaders, may not understand the experiences of low-income Americans.

“I'm particularly worried that if these are the people who are going to be making decisions for the average American, how are they going to be able to make effective decisions with that in mind, [considering] that they aren't fully understanding of what the average American is going through,” Nhieu said.