“Abortion is good.” “Abortion is bad.” “Hate speech is not free speech.” “Freedom of speech is an imperative.” “We need guns for self-defense.” “Reasonable societies ban guns.” None of these statements are true. Not really, anyway.

It seems to me that, at both the national and individual level, the prevailing political outlook for many people is not “my position is … ” but rather, “the objective moral truth is … ” This is hurting our discourse and ability to work together.

As a philosophy and political science major with a focus in political thought, I’ve spent more than my fair share of time considering vague concepts like goodness, morality, and justice. While many disciplines always teach you to learn, one of the deepest benefits of my education has been teaching myself to unlearn. Unlearning that our natural outlook is the objectively best one. This unlearning is something I think we could use more of in our discourse.

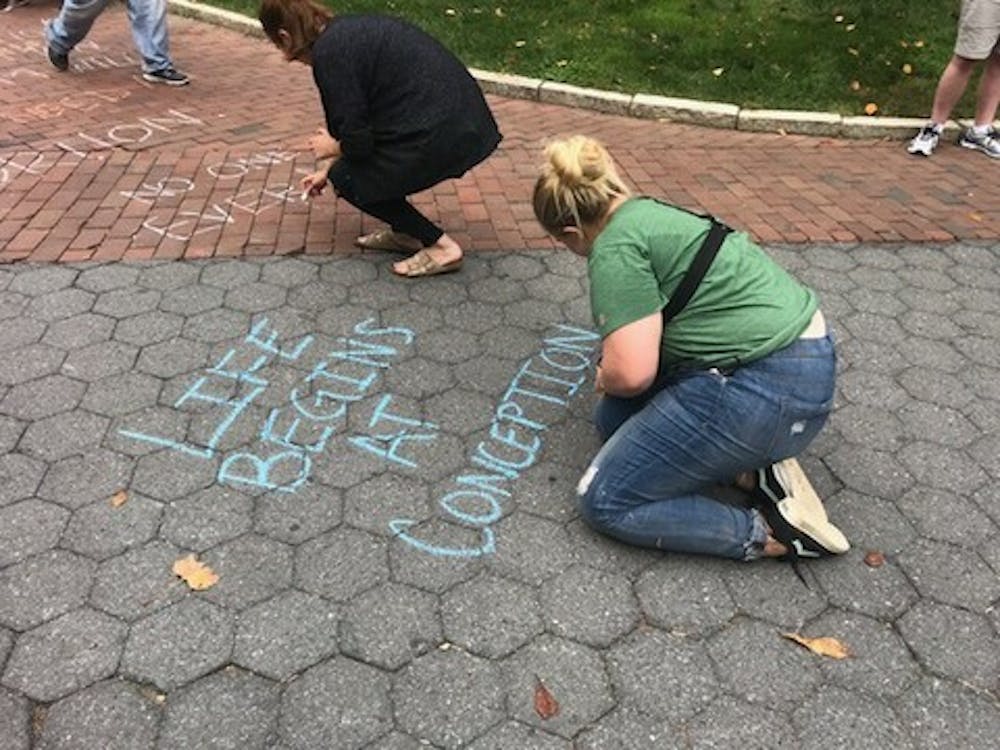

Last year there was a contentious “debate” on abortion between abortion-rights and anti-abortion groups on campus in the form of a chalk fight on Locust. Every day, one group would scribble out or deface the other’s messages, and the pattern would continue.

In a 34th Street feature on the incident, 2017 Wharton graduate Andrea Pascual said, “This was just completely trying to invalidate a stance different from your own.”

More recently, some of the responses I saw (and continue to see) to Penn Law professor Amy Wax’s Philadelphia Inquirer op-ed demonstrate the idea that we think people with fundamentally different views are attacking us.

Maintaining an unwavering conviction that there is an objective truth to which philosophical political outlook one "ought" to have implies that we can just take that position and then calculate what is "good," "just," etc. like we would solve a math problem. But then, how can we grapple with the idea that people disagree?

SEE MORE FROM DYLAN REIM:

You don't need Penn's permission to go the Super Bowl victory parade

In the case of the chalking at Penn, we could just cross out the ideas of anyone we disagree with. They’re wrong. They’re bad people and they know it. We need to block them out, right? We could write ambiguous condemnations of Amy Wax without actually worrying about why or how we disagree with her. We could write “why is she still employed here??” in a Facebook article comment section. She is bad. She doesn’t belong here, right?

Instead of furiously giving up and cursing the air as to why and how so much of society could be so, so misled from the proper outlook, take a breath and realize none of us holds the truth in our hands. "Caring about people" might look very different to you than it does to someone else, but these differences are the result of the same human spirit. A lot of our fundamental opinions aren't generated because we haven't read the right statistic yet or haven't attended the rally that changes it all for us. These differences stem from different philosophical outlooks about what constitutes these vague things like "good" and "fair" and "just," and those outlooks can't be explained away with a passive-aggressive tag on an article we liked.

According to a series of University of Virginia studies, liberals and conservatives actually rely on different sets of moral foundations. On a psychological level, people across the aisle assign moral value differently — with no clear cause. No one is avoiding goodness — we’re just sorting through different ideas of what goodness is.

I wish I could say that morality is like science. I’d love to suggest we run tests and wait for the people in white lab coats to tell us how things are supposed to work. But no matter how desperately we want it to be true, no matter how many tears we shed when Trump was elected, no matter how closely we cling to our originalist Constitutional interpretation, that isn’t the case.

Sure, it will be frustrating to disagree so fundamentally that any compromise will be a heavy concession on both sides. But, we should never declare the very essence of those we disagree with as wrong, and should never be so vain as to believe we have the ultimate truth in the bag. I think going forward with that in mind will make us better in our moments of both conflict and cooperation.

DYLAN REIM is a College senior from Princeton, N.J. studying philosophy and political science. His email address is dreim@sas.upenn.edu.