A new drug is saving lives while filling Penn’s coffers.

Lomitapide, marketed in the United States under the name Juxtapid, is a prescription drug that treats homozygous familial hypercholesterolemia, a rare genetic disorder in which the liver is unable to remove a type of bad cholesterol from the blood. Penn, which developed Juxtapid, has a licensing deal with Aegerion Pharmaceuticals, the company that makes and sells the drug.

The deal has so far proved financially successful for both parties. This June, Penn announced that it had sold part of its ownership of Juxtapid to an anonymous buyer for $55 million. Penn will also receive royalties of up to 10 percent on sales of Juxtapid.

The monetization of Juxtapid “contributed to a $127 million positive revenue variance” at Penn for the most recent fiscal year, which ended in June, according to coverage of the Board of Trustees’ September meeting in the Almanac.

Juxtapid joins three other drugs that are part of Penn’s portfolio. The licensing of drugs and other “biomedical activities” account for 75 to 80 percent of Penn’s licensing income. For the financial year of 2011, this total licensing income was $14.4 million, and the number is expected to increase “significantly” for the financial year of 2012, according to John Swartley, the executive director of the Center for Technology Transfer and the associate vice provost for research at Penn.

Penn requires all research to be published openly and conducted without conflict of interest issues. However, Penn is free to profit from any research it owns.

All this revenue is redirected into Penn “according to a specific formula,” Swartley said, who summarized the policy by saying, “inventors and their laboratories receive a significant share followed by the inventors’ school, department and the University Research Fund.” Therefore, the Design School is much less likely to benefit from Juxtapid’s success than the School of Medicine.

Aegerion Pharmaceuticals has also financially benefitted from the deal. Aegerion’s stock soared from $14.11 per share in October 2011 to $93.32 per share as of press time, more than a six-fold increase in a two year time span.

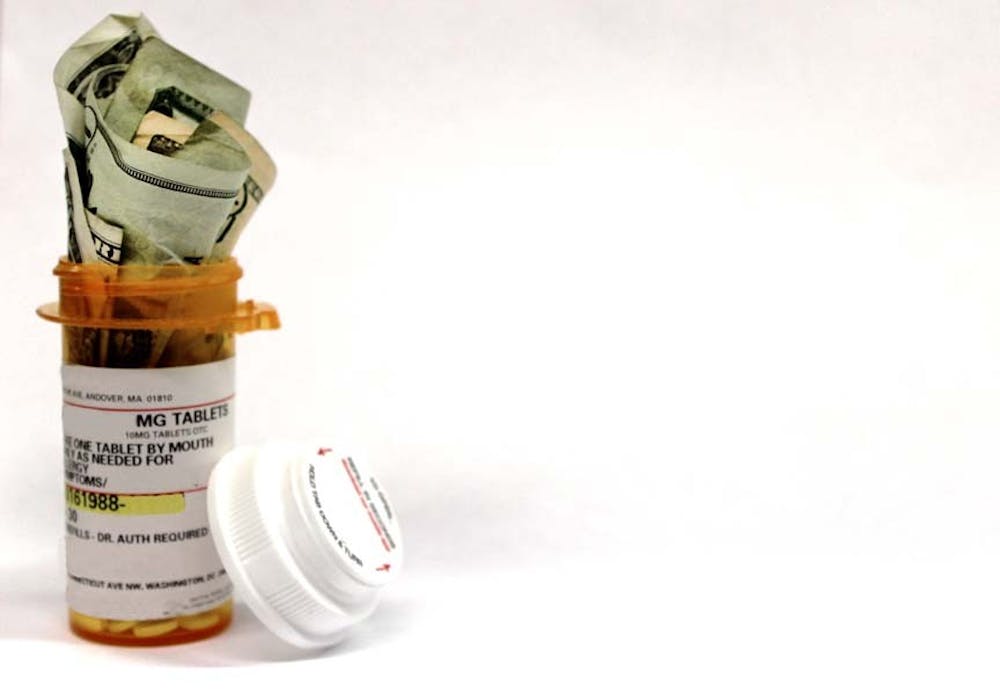

All this financial success comes at a steep cost. A yearly treatment of Juxtapid, which is a pill that is taken daily, costs $295,000.

Related: Penn Med collaboration could generate big revenue

Juxtapid may still be affordable to those who need it though. Currently, insurance providers Aetna and Independence Blue Cross cover the cost of Juxtapid. Aegerion also has a patient assistance program to aid those without insurance.

Daniel Rader, a physician and a professor at the Perelman School of Medicine who was the primary developer of Juxtapid at Penn, acknowledges the high cost of the drug.

“There’s no question, you look at that money and you say, that’s a lot of money per year to pay for a medicine,” he said.

Rader, who chairs the scientific advisory board at Aegerion, defends the high cost of Juxtapid due to its orphan drug status. Orphan drugs are a special classification of drugs by the Food and Drug Administration which treat rare diseases that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S.

Rader estimates that around 1 in 400,000 people in the US are affected by HoFH.

“It’s a pretty rare but pretty bad disease that actually results in high cholesterol as children. Untreated, they rarely live beyond age 23,” Rader says.

Research suggests that Juxtapid can double that projected lifespan, which makes it the best treatment for HoFH so far. In the past, patient had to be hooked up to IV machines every one to two weeks so that cholesterol could be flushed from their bloodstream, a procedure Rader called uncomfortable and time-consuming. This treatment had a similar price tag to Juxtapid.

Juxtapid’s development started when Bristol-Myers Squibb donated the rights to the drug to Penn. From there, Rader and a team of scientists in Penn Med worked to perfect the drug in clinical trials. In May 2006, Penn entered into a partnership with Aegerion, which helped fund Rader’s research.

The drug is currently under patent until 2015, but the company has requested a five-year extension on their patent. After the patent expires, other companies will be able to access the research and produce their own version of Juxtapid, which could lower the cost of the drug, according to Rader.

For now, Rader says the high cost is unfortunately unavoidable because “the big companies don’t want to develop drugs in the orphan space. It’s hard for them to make money off of them” to offset the research costs.

Arthur Caplan, a former professor of medical ethics at the Perelman School of Medicine who is now at New York University, says of the high cost of life-saving drugs, “Is it ethical? No, but it’s what the market will produce … The prices charged are mostly what the drug company can get away with.”

However, Caplan does not see Penn as a “the culprit in the pricing area,” although he does believe that “we haven’t had enough protest from medical organizations about prices.”

Instead, Caplan believes that the problem lies with the fact that the government does not regulate drug prices.

“One of the biggest moral failures in health care is that we haven’t really had an examination of prices.”

A previous version of this article identified John Swartley as the vice provost for research at Penn. He is the associate vice provost.

Additionally, Penn sold the $55 million stake in the drug to an anonymous buyer, not Aegerion.