I found out I was pregnant in a Starbucks bathroom, only a few weeks after starting my first year at Penn. I was 18, and I did everything to keep it a secret. Buying a test on campus risked fellow students seeing me, so I walked about 15 blocks downtown to the Rittenhouse CVS. After that, I headed into the Starbucks across the street, where I remained, hyperventilating, until my tears subsided enough to be able to walk outside again.

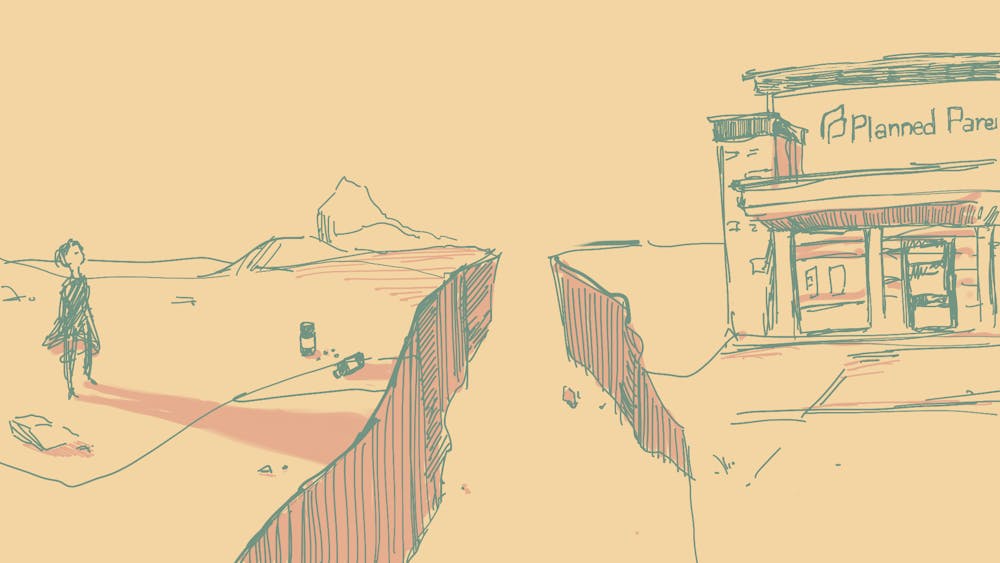

I knew right away that getting an abortion was the right decision. In fact, never did I dwell on any of the concerns that would soon be hammered into my head by the State of Pennsylvania nor the anti-abortion picketers I ignored outside the doors of Planned Parenthood at 12th and Locust. The bright future I strived — even competed — to achieve was in jeopardy now, so I had to do what was necessary to fix it.

Yet I still felt shame, which fueled my effort to keep quiet. Growing up, I was raised with a chilling fear of this day. Getting pregnant in high school or college was a non-option, never mind the choice to get an abortion.

At the time, my only strategy moving forward was a steely compartmentalization, though it was (and remains) unsustainable. The ability to connect with a community who understands the messy, contradictory nature of these feelings would have changed my mental health for the better.

I understand the roadblocks currently in place to get a safe abortion to be traumatic and unnecessary, and I am arguing in this piece that sharing our stories publicly can not only demonstrate how impossible it is to escape emotionally unscathed, but also help others who may be painfully processing their experiences in isolation.

Instead, the government made more emotional what I was trying to endure as clinical. At the first appointment, the nurse gathered me and the other patients to watch a mandatory video that emphasized the gravity of our decision and cited misrepresented facts about the percentage of us who would go on to regret this.

Afterwards, I needed to take a urine test, blood test, and undergo a transvaginal ultrasound before continuing on further. Looking back, I question the medical necessity of such invasive procedures, as the requirements vary so widely across jurisdictions. For example, the U.K. Government rapidly pivoted to allowing access to medical abortion pills by mail in the height of COVID-19, and doctors and medical health professionals advocated to keep the program in place as COVID-19 restrictions eased.

Abortion regulations in Pennsylvania have developed since 2010. Patients now must receive state-mandated counseling that includes information shifted to discourage the choice to have an abortion, and then wait 24 hours before the procedure or the medication is provided. This delay forces many to travel long distances to a clinic more than once and take extra time off work.

For my second appointment, I stayed at the clinic all day just to get two pills. Even more, the whole thing cost $800, which I was privileged enough to have in cash from my high school graduation money. Currently in Pennsylvania, health plans offered under the Affordable Care Act can only cover abortion if the patient’s life is endangered, or in cases of rape or incest.

Inequitable access to abortion in the United States is obviously nothing new.

The LA Times reported that University of California and California State University are set to provide abortion pills to students for about $50. Even some colleges outside California, including the University of Massachusetts Amherst and the University of Illinois Chicago, plan to make medical abortions more easily available to students.

I am not writing this to lay out why Penn should follow suit. It’s easy for me to say abortions should be cheaper and simpler to access. It’s harder for me to admit that I guarded a stigma about sharing my experience, even as the fragility of the right to choose became more evident. To tell an acquaintance might be over-sharing. To tell a colleague would be unprofessional.

I am writing this now because I am afraid a future employer may find this on Google. That fear was planted there by a process that is hostile and condescending by design. These regulations have an insidious impact on how people process their experiences of getting an abortion. While they are still in place, one power we have is not to let them silence us.

Six states mandate that patients look at their ultrasound and have the nurse describe the image to them prior to receiving an abortion.

Some patients may turn to see a stubborn collection of cells, while others may bite their lip to hold back tears. No matter the reaction, such measures are constructed to wear people down, to manipulate us. They only build upon the shame I grew up with.

There is serious work to be done in the wake of overturning Roe v. Wade — and perhaps we do await Penn providing $50 abortion pills in the future. In the meantime, let’s not move backwards. I hope speaking openly and coming forward about my experience having an abortion when I was at Penn helps other students navigate a similar terrain.

BRIDGET MCGEEHAN is a 2014 College graduate in English, living in London. Her email is bridgetcmcgeehan@gmail.com.