Maybe it was a generator explosion, Erica Denhoff thought. She asked the policeman if it was safe to continue.

He said yes. They would tell her if it stopped being safe.

But a few miles later, there were more Boston police officers and more frantic people trying to reach their loved ones on the phone lines that would be down for hours.

Erica knew her father, mother and brother were waiting for her at Mile 24, near the final homestretch of the 26.2-mile trail.

The police finally told her she had to veer the course. “But my family’s there,” she said.

“We cleared up the area 20 minutes ago,” the officer responded.

***

Rick Reinhart didn’t have to ask — he knew what it was.

Related

4/17/13: Penn grads, student reflect on Boston aftermath

4/16/13: Community shares shock and stories from Boston Marathon

4/16/13: Alum journalists reflect on covering Boston explosions

Campus Resources

Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS)

215-898-7021

215-349-5490 (Nights and weekends. Ask for CAPS counselor on call.)

University Chaplain’s Office

215-898-8456

Student Health Service

215-746-3535

Office of the Vice Provost for University Life – Student Intervention Services

215-898-6081

Office of Student Affairs

215-898-6533

Not city noise, as many had speculated. Not a car backfire. Not fireworks.

“They were both explosions,” Rick said. “I was an active and reserve Army officer. And I recognized the sound of something exploding.”

Monday at 2:50 p.m., Reinhart, who earned a master’s degree from Penn Engineering in 1971, was less than a mile away from the finish line on Commonwealth Avenue, just before the point where runners make their final turn onto Boylston Street.

Almost right away, race officials halted the sea of runners, about 5,000 strung out along the streets.

After ambulances, fire trucks and police cars raced by, rumors began to circulate that a propane tank had blown up in a nearby restaurant, or perhaps it was a gas explosion.

But if Rick’s 28 years of military experience didn’t give it away, the plumes of smoke rising above the buildings did.

“I’m thinking to myself, ‘That was no gas explosion,’” he said. “It was just too percussive a sound for it to be anything but a [bomb] explosion.”

Rick wanted to call his wife but couldn’t. He was over 300 miles away from his Philadelphia home with no clothes, no money and no cell phone.

***

“We get there and it was such a happy occasion,” Joe Denhoff said. He and his wife had traveled up from Rhode Island to see their daughter, a 2008 College graduate, run. “People were upbeat, having fun …[the crowd] was motivating every runner that went by.”

His son, Chase, was looking at something on his smartphone. “Want to hear some breaking news?”

“Yeah, sure.”

At first, they thought it was a hoax because they saw and heard nothing from their vantage point at Coolidge Corner.

Next thing they knew, the police instructed everyone to leave the area, without any explanation.

“What about the runners?” Amy Denhoff asked an officer.

“Don’t worry about the runners.”

“I have to. My daughter is a runner.”

***

In 1996 and 2012, Judy Reinhart was in Boston with her husband, cheering him along from the bleachers as he ran in the nation’s most prestigious marathon event.

But this year she was watching from home. Rick was running a marathon for the 28th time and his third in Boston. Plus, her last two times there — one in frigid temperatures, the other in 90-degree heat — weren’t great experiences.

After a few hours, when the winners had already crossed the finish line, Judy turned off the TV, not expecting to see Rick.

Around 3 p.m. her goddaughter called, asking for her uncle. The next three hours were three of the longest in Judy’s life.

Phone calls started pouring in, and she kept answering. It was never her husband.

“People who called would keep asking me if I was all right and I would say, ‘No! I’m not all right!’” Judy said. “And then I’d start crying.”

Then, finally, she saw Rick on TV. Or at least she thought she did.

It was the now-iconic photo of the older man in a red singlet being knocked over by the blast at the finish line that she thought was Rick.

“I have never been so glad to see anybody on the ground alive and well in my whole life,” she said. “I could tell that this person was not seriously injured.”

It wasn’t Rick, but she didn’t know it at the time.

“I’m going to pretend that’s Rick because I hadn’t heard from him,” Judy told herself. “We all decided that was Rick and he was OK.”

***

This was Erica’s second Boston Marathon, and she was running for the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute with 550 other runners. Last year, Boston had been scorching hot — reaching almost 90 degrees Fahrenheit — on the historic Patriots’ Day. Erica had brought her phone with her. Fire departments had spray hoses in place to keep runners from dehydrating.

By the end of the race, her phone was waterlogged. She decided she wasn’t going to bring her phone this year.

When she hit Beacon Street, an officer told her to make a left. She made a right instead and ran to her house in Brookline, about 10 minutes away.

She didn’t have her key though. At a park near her house was a woman playing with her child.

“Can I borrow your phone?”

***

About an hour had passed since the race had been halted, and Rick still knew nothing.

“There we were, huddled together,” Rick said. “You’re all sweaty and suddenly you stop and you’re in a big crowd, so you can’t really do much of anything else.”

Around him, fellow competitors were experiencing muscle cramps. Others were throwing up. When marathoners finish a race, they’re supposed to keep moving — coming to a complete stop is the worst thing they can do.

Eventually, residents began coming out of their houses with boxes, trash bags and old clothes. It was a cool day in the mid-50s, but colder with the breeze, and runners were wearing but little attire.

“There were people in the crowd who were getting hypothermic,” Rick said.

He still hadn’t reached his wife. Eventually, officials instructed everyone to retrieve their belongings, which had been relocated nearby. Rick went, but his weren’t there. He tried his hotel — The Westin Copley Place, which is less than a block from the finish line — but no one was allowed in. It had been turned into a command center for law enforcement and federal officials.

Unable to get to his belongings, which included his phone, he found a nearby train station to wait in and stay warm.

“A kind woman there lent me her cell phone, and I called Judy at about 5:30 to tell her I was alive and well,” he said.

In the couple’s short conversation, Rick learned of the extent of the tragedy for the first time.

***

Maybe Erica had already run through and we missed her?

The Denhoffs were looking up and down the street for their daughter. Coolidge Corner had mainly been cleared out, besides a few stragglers. There were no more runners on the trail.

“This was probably the worst part — did she go by? Where is she? Did the police stop the runners?” Joe said. They couldn’t reach her by phone.

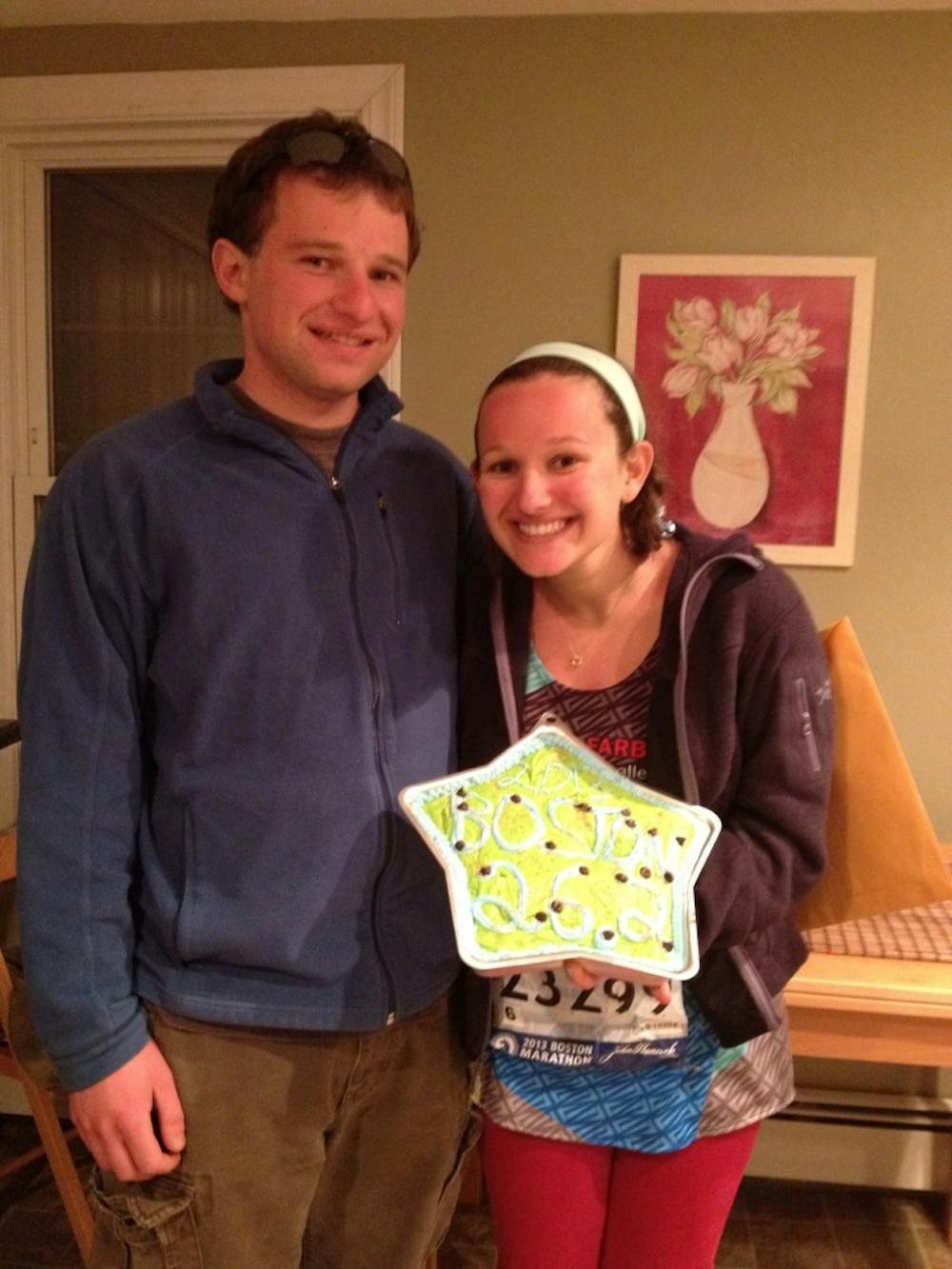

Amy’s cell phone lit up. It was a text from a number she didn’t recognize. Erica was home.

Chase ran to the house, about half a mile away, and found her sitting outside.

***

Rick reached home around 5:30 p.m. Tuesday. After a restless night where she “kept hearing explosions going off,” Judy would be able to sleep soundly at last.

“He’s here and that’s all that matters,” she said.

Rick has already qualified to run Boston next year, and he’s not averse to doing it again. Judy won’t tell him he can’t, but she’s not exactly keen on the idea.

“Boston is low on my list of great marathons,” she said. “I prefer Paris.”

***

“We started getting a multitude of phone calls from people we knew who were concerned,” Joe said. “About 50! I didn’t think I knew that many people cared about me.”

Amy immediately posted a photo of Erica on Facebook so that friends and family would know she was okay. “Social media works for us older people too,” she said.

On Tuesday, Erica went back to work at the Children’s Hospital in Boston. She saw many policemen with assault rifles and the general atmosphere was one of devastation.

“It’s very reminiscent of 9/11, reminiscent of that fear,” she added.

Erica will run Boston next year for Dana-Farber again. She and her colleagues have raised over $2.8 million this year alone. “Fear can’t overshadow the good we’ve done.”

In addition to the larger, more obvious ways, “this bombing affects people in little ways and will keep on affecting people,” she said. “Copley Square is one of the best places in the city — how are people going to go back to the blood-stained sidewalks?”

Related

4/17/13: Penn grads, student reflect on Boston aftermath

4/16/13: Community shares shock and stories from Boston Marathon

4/16/13: Alum journalists reflect on covering Boston explosions

Campus Resources

Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS)

215-898-7021

215-349-5490 (Nights and weekends. Ask for CAPS counselor on call.)

University Chaplain’s Office

215-898-8456

Student Health Service

215-746-3535

Office of the Vice Provost for University Life – Student Intervention Services

215-898-6081

Office of Student Affairs

215-898-6533