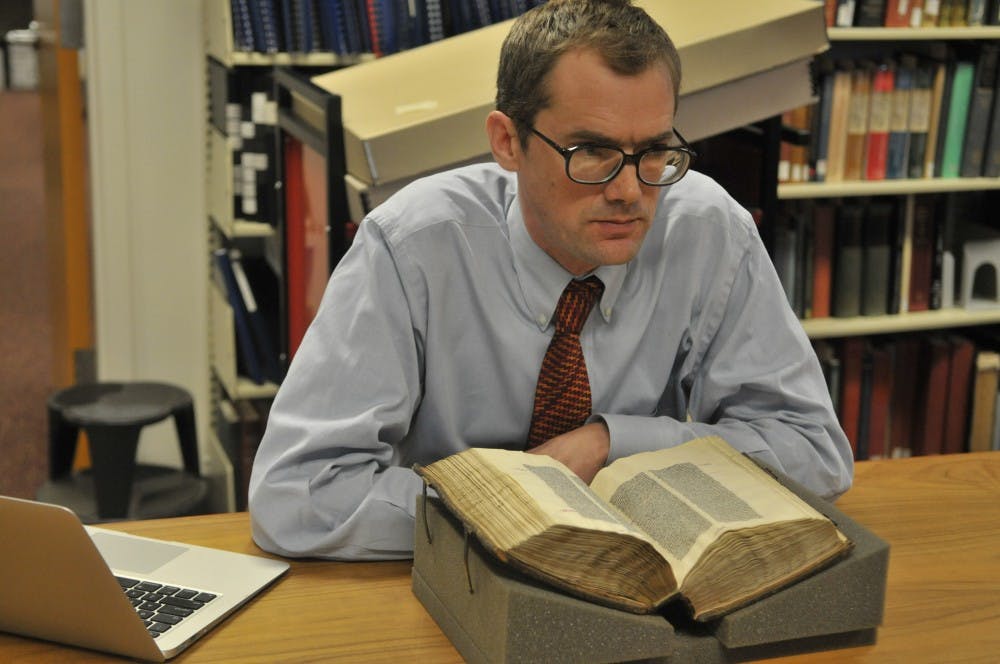

William Noel, the founding director of the Schoenberg Institute for Manuscript Studies at Van Pelt Library, inclines himself over a thirteenth-century Bible and unhooks the clasps that hold the pages together. He leafs through, uncovering neat little columns of blackletter writing meticulously inscribed by a monk some eight centuries ago.

“This book is an archaeological dig,” he said. “When you hold it, you hold the weight of history in your hands.” Medieval books were written on parchment or vellum — that is, paper made from the hides of animals. In this case, “You’re holding approximately 100 sheep.”

“It’s the mark of a life well-spent,” he added, alluding to the hours and hours of labor required to create a manuscript of this quality.

Noel, a plucky Brit who still recognizes the importance of a clean shirt and tie, arrived at Penn in September from the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore. Before that, he spent 12 years at Cambridge University, where he received his doctorate in art history in 1993. Noel grew up “sailing on the Essex marshes” and developed a love for medieval history early on when his father gave him “A Nursery History of England.” He recalled the stories of “Canute the Great and King Alfred and the cakes” — apparently a historical king of England who let cakes burn at some time or another.

“I fell in love with the romance of the Middle Ages,” he said, “and never really left it.”

Noel’s life took an unexpected turn, however, when a book called the Archimedes Palimpsest arrived on his desk at the Walters in 1999. “A palimpsest is a document where the original text has been scraped off and overwritten with another text,” Noel explained. “Depending on how thoroughly it’s been written over you can recover the text underneath.”

In this case, the book Noel received contained a hitherto unknown text by the Greek mathematician Archimedes, as well as two other unique ancient texts — all hidden beneath a thirteenth-century prayerbook.

Using several different wavebands of light, the conservators at the Walters were able to create “pseudocolor” images of the manuscript, making the ancient text clearly legible underneath. For the pages that had been painted over with forgeries, the team visited the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center to use their particle accelerator to image the text. All the data from the project were then published online under a Creative Commons license for anyone to use.

The Palimpsest Project brought Noel a great deal of media attention — which included a TED talk in 2012. In his talk, he criticized the copyright restrictions that museums and major universities place on their digital manuscript collections.

“The web of ancient manuscripts of the future isn’t going to be built by institutions,” he said. “It’s going to be built by users.” Noel’s dedication to “open-access data” has been steadfast — in his time at the Walters he created a vast online library of the museum’s manuscript collections accessible to anyone.

Noel has brought his ideas about the democratization of information to his new job as director of the Special Collections Center at Penn, which has already been in the process of digitizing manuscripts through the Schoenberg Center for Electronic Text and Image since 1996.

What Penn is doing, Noel said, is “rather radical — in my world.”

“The great danger to historic collections is not that they’re overused but that they’re becoming irrelevant,” he added. Digitizing them may be the solution.

Noel used an example he has used before: “Why do people go and see the Mona Lisa?” he said. “Because they already know what she looks like.”

“What historic collections have is largely unknown,” he said. “Rather than detracting from the importance of the original, the digital image can actually increase the aura of the original.”

The Rare Book and Manuscript Library’s reading room on the fifth floor of Van Pelt has seen a dramatic increase in the number of visitors in recent years, due largely to the availability of digital materials and an unprecedented hands-on policy for undergraduates. According to Noel, once people get the notion that this image they see on their computer screen “actually exists somewhere,” they want to see it in real life— and will feel especially compelled to do so once the library unveils its new sixth-floor reading room and conference space on April 19.

In short, the books won’t be going anywhere any time soon. As he sits in the reading room surrounded by invaluable and in many cases totally unique books, Noel makes sure to drive that point home.

“There are lots of things that originals can do that digital images can’t do,” he said. Likewise, “there are lots of things that digital images can do that original manuscripts can’t do. They can be everywhere all at once. You can blow them up to any size. You can write on digital images.”

He paused, adjusting his thick-framed glasses. “But don’t you dare write on my 13th-century manuscript.”

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

DonatePlease note All comments are eligible for publication in The Daily Pennsylvanian.