It's comforting to imagine ourselves as heroes in the records of history, standing on the “right side” of moral battles. Many of us believe that, if given the chance, we would have marched during the Civil Rights Movement, rallied against Apartheid, or fought for suffrage. Yet, in the routine of our daily lives amidst contemporary injustices, one must ponder — would we really be any different?

Our education often champions a teleological narrative of history, in which we’re steadily progressing towards a better, more enlightened era. It’s a comforting thought, like a gentle pat on the back telling us to relax because things are on the right track.

But this notion is seriously flawed.

The same structures that enabled horrific atrocities in the past are still around, just dressed up in modern clothes. For instance, recent critiques by UN experts highlight how systemic racism within United States police and courts is not just lingering prejudice but an evolution of past injustices, deeply rooted in the era of slavery and Jim Crow laws.

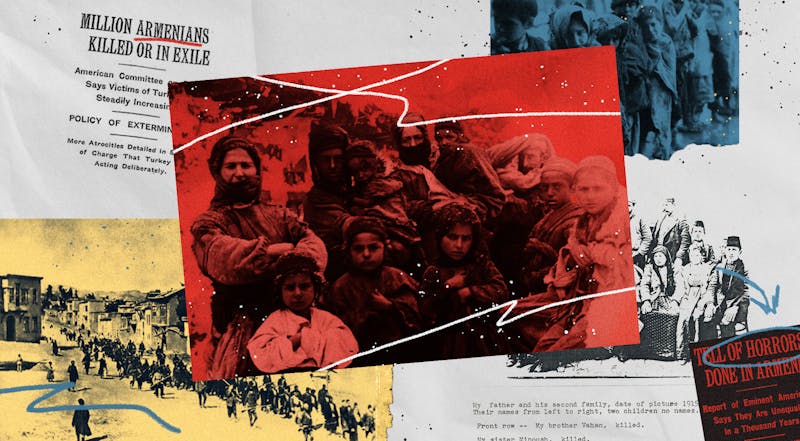

Globally speaking, our international track record — from failures to intervene in the Holocaust to more recent crises in Sudan’s Forgotten War, Myanmar’s ongoing Rohingya genocide, or Australia’s controversial refugee detainment camps — shows a disturbing pattern. The pledge of “never again” seems to have quietly turned into “again and again,” as the international community repeatedly fails to act decisively.

More pressingly, teleological storytelling risks misleading us into believing that the unfolding of human affairs is entirely preordained and inevitable. In reality, history is the slow accumulation of individual choices and actions. When we buy into the myth of inevitability, we risk absolving ourselves of the active role we must play in shaping our future.

The hesitancy to dive into the waters of activism is hardly a novel sentiment. After all, if the fires aren’t from our own backyards, we feel less urgency to douse them. This psychological and social distance tends to mute our rallying cries. However, activism that demands we alter our own beliefs or lifestyles isn't just uncomfortable — sometimes it seems downright impossible.

Psychologist Paul Slovic has given a name to this overwhelm: “psychic numbing.” This phenomenon describes how our empathy wanes as the number of victims in a tragedy swells. A sense of inefficacy tricks us into thinking our acts of kindness are drops in an ocean too vast to ever fill. It’s a cruel irony of human psychology: The more widespread the suffering, the less potent our individual efforts seem and the weaker our impulse to help becomes.

Perhaps even more alarmingly, there is an increasing fear of social or professional repercussions that significantly stifles our voices. It is deeply troubling to observe how pro-Palestinian students and professors across U.S. college campuses have to balance their advocacy with the looming threat of jeopardizing future career prospects. Consider Asna Tabassum, the University of Southern California’s class of 2024 valedictorian, who was barred from speaking at graduation because of a hate campaign in response to her pro-Palestinian stance. Adding to these concerns, more than 100 protesters were arrested at Columbia University last week. Even here at Penn, the University banned the activities of Penn Students Against the Occupation of Palestine and condoned police detainment of students for chalking "Let Gaza live" across Locust Walk.

This effect on student activism reveals a chilling crack in the foundation of our professed freedoms. If the cost of speaking out is the forfeiture of future opportunities, then surely we must question the integrity of our societal structures that respond with censorship. Are we fostering a culture where advocacy is only for those who can afford to be fearless, or worse, excludes certain people altogether?

We must acknowledge that inaction is a privilege fraught with profound consequences. The Milgram experiment from the 1960s illustrates this point. Designed to probe the psychology of genocide, the study revealed how ordinary people could be driven to commit horrifying acts by obeying authority. This demonstration of compliance underscores a broader truth: When we opt to stand by, whether due to psychic numbing, perceived inefficacy, or fear of repercussions, we risk becoming unwitting accomplices in perpetuating harm, echoing the dark chapters of history we so readily condemn.

Despite formidable barriers, there are uplifting instances of people surmounting these obstacles to drive meaningful change. The advent of social media has been particularly transformative, amplifying previously marginalized voices and their reach around the world. For instance, the Iran protests that began in September 2022 saw thousands, led predominantly by young women, take to the streets and social media to demand reform following the death of Mahsa Amini in police custody. Similarly, Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 led to worldwide antiwar protests, while the global climate protests in September 2023 marked one of the largest coordinated actions post-COVID-19 for climate advocacy.

Together, these movements reflect a global trend toward challenging the status quo and advocating for far-reaching societal changes.

As we contemplate our hypothetical heroism in past conflicts, it is crucial to scrutinize our current actions. Claiming potential activism in the past is easy self-assurance; the real test of our character is reflected in how we address today's injustices.

Otherwise, perhaps our imagined historical heroism is just that — an imagination.

LALA MUSTAFA is a College sophomore studying international relations and history from Baku, Azerbaijan. Her email address is lmustafa@sas.upenn.edu.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate