In our age of misinformation and propaganda, understanding conflicts like Nagorno-Karabakh has never been more crucial for fostering informed global citizenship. The conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the Nagorno-Karabakh territory is as complex as it is deeply rooted.

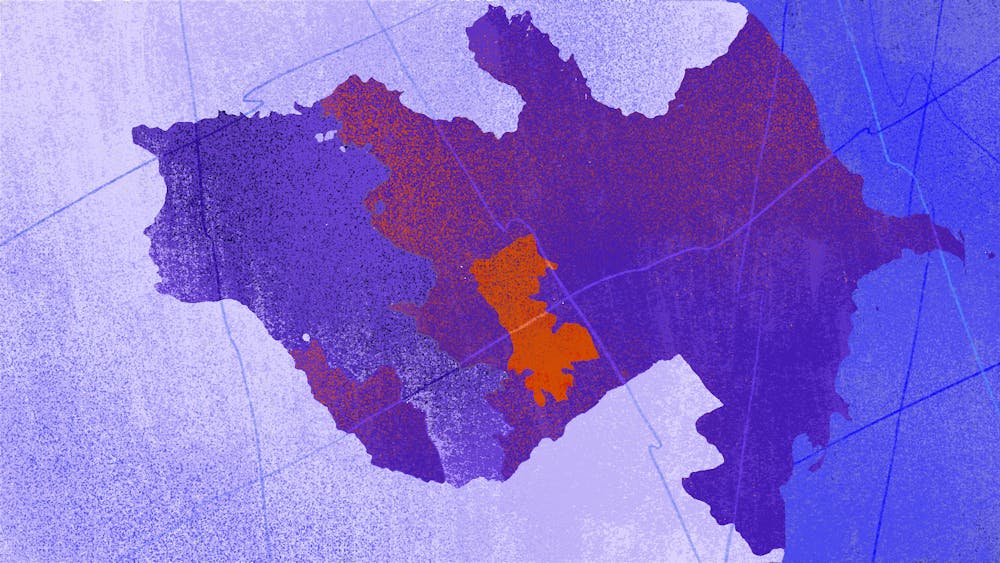

Before delving into any details, it is imperative to acknowledge one crucial fact: the internationally recognized status of the land as Azerbaijani territory.

While Karabakh holds historical and religious significance for Armenians, it serves as an equally integral part of Azerbaijani culture. Karabakh stands as a cradle of Azerbaijani heritage, having nurtured celebrated poets, musicians, and prominent historical figures such as Khurshidbanu Natavan, Bulbul, Molla Panah Vagif, and Uzeyir Hajibeyov. During Soviet times when Karabakh was undisputedly part of Azerbaijan’s Soviet Republic, Azerbaijanis and Armenians coexisted there, contributing to a vibrant cultural mosaic.

However, this long-standing harmony was shattered following Armenia's separatist claims to Karabakh, leading to the First Karabakh War and the occupation of one-fifth of Azerbaijani land. The aftermath of this saw the destruction of cities and civilian life, the emergence of Azerbaijani refugees, and attempts at the erasure of our cultural heritage. Between 600,000 to 800,000 Azerbaijanis were forcibly expelled, and 20,000 were killed. The memorial and monument of Natavan, for instance, was destroyed, her tomb looted, and her remains stolen. So, why did this occur?

Beginning in 1987, as the Soviet Union began to disintegrate, the Armenian separatist minority in Karabakh sought unification with Armenia through the sentiment of "miatsum." In 1991, an illegitimate referendum against both international and USSR law was conducted by this separatist group to sever Azerbaijan’s ties to Karabakh, despite a boycott by its Azerbaijani population. This move mirrored Russia's assertion of a Russian majority in Lugansk and Donetsk as a justification for annexation; however, the mere presence of an Armenian majority in Azerbaijani land does not inherently warrant the region's belonging to Armenia.

Nagorno-Karabakh thus remained, nonetheless, internationally acknowledged as part of Azerbaijan. As per its agreement with the Alma Ata Declaration of 1991, this fact was also recognized by Armenia itself.

The gravity of the situation led the international community, as represented by the United Nations, to release four U.N. Security Council Resolutions (822, 853, 874, and 884) and U.N. General Assembly resolutions 49/13 and 57/298, demanding the withdrawal of Armenian forces from the occupied territories, an appeal that Armenia consistently disregarded.

Among the darkest chapters in this conflict stands the Khojaly Massacre, one often denied by Armenia. Human Rights Watch labeled it as one of the most devastating incidents in the entire conflict, during which 613 civilians were killed and mutilated in the town of Khojaly by Armenian forces.

Throughout the conflict, many historical Azerbaijani monuments, museums, and archaeological sites were destroyed. At least 65 mosques in both Karabakh and East Zangezur were looted, desecrated, and turned into pigsties and cowsheds.

In 2019, against the backdrop of Armenia’s evolving and increasingly hardened stance to advance further into Azerbaijan, threats to seize more land by Armenia’s Ministry of Defense, Tonoyan, were made. He demanded a "new war for new territories." Armenia’s Prime Minister, Pashinyan, additionally declared “Karabakh is Armenia. The end," crushing room for potential negotiations and leading to the Second Karabakh War.

In the course of the Second Karabakh War in 2020, Armenia’s forces shelled densely populated areas using ballistic missiles and unguided artillery projectiles. Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International documented these multiple deliberate attacks in the cities of Barda and Ganja which claimed the lives of 91 civilians while leaving over 400 civilians hospitalized with serious injuries.

Azerbaijan, thrust once again into conflict, was able to reclaim a significant portion of its territory. Yet, the level of destruction by Armenian forces found on Azerbaijani land was unprecedented. Most evidently, the city of Aghdam, established in the 18th century and home to 40,000 residents before the war, has been dubbed the "Hiroshima of the Caucasus".

After the continuous refusal of Armenian forces to leave Azerbaijani land (as was agreed by the 2020 Trilateral Agreement) and constant military provocations, Azerbaijan took defensive measures which led to the complete capitulation of separatist military units on Sept. 19, 2023. This was a pivotal moment in its history, marking a full restoration of Azerbaijan’s occupied land since its independence.

Presently, approximately 2,000 Azerbaijanis have managed to return to their homes. However, this task is fraught with challenges, as vast territories lie marred by the presence of landmines and unexploded military ammunition.

In the aftermath of conflict, narratives often distort the truth, unfairly labeling Azerbaijan as the perpetrator of ethnic cleansing. Armenia has alleged a humanitarian crisis due to Azerbaijan’s creation of checkpoints in the Lachin Corridor that linked Karabakh to Armenia and which, ironically, facilitated Armenia's transportation of unauthorized, and often military, goods through it. However, an alternative for the supply of goods to Karabakh was created in the form of the Aghdam-Khankendi road within Azerbaijan itself. This route delivered aid from the Red Crescent Society and the International Committee of the Red Cross directly to Karabakh Armenians. Yet, the separatists' refusal of aid through this road, despite their prior demands for humanitarian assistance, reveals a political motive to challenge Azerbaijan's legitimate control over Karabakh. Azerbaijan, like any country, has the right to regulate its own territory and limit foreign intervention, especially from opposing forces; with my points listed above in mind, it has done so while ensuring the safety of its Karabakh Armenians.

It's vital to clarify the present reality: Karabakh Armenians may leave or return from Karabakh without fear of persecution, as verified by the U.N. Their recent mission found no evidence of violence against civilians or infrastructure destruction post-ceasefire. The legal definition of genocide encompasses violent attacks with intent to wholly or partially destroy a certain group. However, there is no evidence to support claims of violent attacks against civilians post-ceasefire nor any intent to annihilate the ethnic Armenian group: It has always been Azerbaijan’s goal to bring back Azerbaijani natives to their lands while also allowing for Armenian residents to remain as integrated, equal citizens.

Preventing a nation from finding a solution after the occupation of its territory through a smear campaign detracts from peace efforts. Having reclaimed our territory, we are not inclined to jeopardize these gains by invading Armenia or going against international law. Those choosing to leave Karabakh have refused supplies from Aghdam and spurned Azerbaijani citizenship in Azerbaijani territory out of nationalist tendency. This contrasts sharply with when Azerbaijanis faced killings and forced expulsion in the '90s from their own homes.

However, this transient state of affairs does not foretell Karabakh’s permanent fate.

After over three decades of warfare of defending our sovereign integrity, the Azerbaijani people yearn for respite. Addressing this collective desire for peace, President Aliyev articulated the need for collaborative efforts at the Second Azerbaijan National Urban Forum: “It's time really to sit together … and to work on the draft peace agreement.”

Azerbaijan stands as a testament to the coexistence of diverse ethnic communities, a vibrant tapestry that includes Turks, Russians, Talyshs, Lezgins, Jews, Kurds, Tats, Assyrians, Udis, Avars, Georgians, Tsakhurs, Ukrainians, Tatars, Talyshi, and many others, all with their unique cultures, languages, and religions. Together, we make up the people of Azerbaijan and call ourselves Azerbaijani citizens. This rich diversity exemplifies the potential for peace in the Caucasus.

It is a potential that I, and many Azerbaijanis, fervently believe in.

LALA MUSTAFA is a College sophomore studying International Relations and History from Baku, Azerbaijan. Her email is lmustafa@sas.upenn.edu.