When a team at the Mütter Museum of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia opened an exhibit on the 1918 influenza pandemic in fall 2019, they had no idea just how relevant the exhibit would become just months later.

The exhibit, "Spit Spreads Death: The Influenza Pandemic of 1918-19 in Philadelphia," highlights how Philadelphia was impacted by the 1918 influenza pandemic, which began spreading in the city after a war bond parade on Sept. 28, 1918. With a death toll of nearly 16,000, the city became an influenza epicenter in the United States — which was home to about 675,000 deaths amid the global pandemic that infected nearly 500 million people worldwide.

The exhibit opened in the Museum last fall on Oct. 17, 2019, just over 101 years after the parade that led to Philadelphia's virus outbreak. Since shutting its doors to the public due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, it has reopened the exhibit with a virtual tour.

“We were just as surprised as anyone about the [COVID-19] pandemic for sure,” Museum Manager and Projects Manager Nancy Hill said. “But part of why we chose the topic was that we figured there'd always be some sort of public health issue in the press that people could relate this past historical experience to.”

The exhibit originally included hypothetical questions about how a pandemic would impact the modern world, Hill said. It features photographs, artifacts, and panels of quotes from Philadelphians who lived through the 1918 pandemic.

As this hypothetical grew into a reality, Hill and the Spit Spreads Death team created an addendum for the exhibit related to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Museum is now offering a 16-minute virtual tour, animations of Philadelphia’s influenza spread, and a map of Philadelphia’s 1918 pandemic landmarks.

One week into Penn's fall 1918 semester, Pennsylvania issued a statewide ban of large indoor gatherings and closed saloons and theaters. While the president of the Philadelphia Board of Health shut down the city's schools and churches, he allowed Penn's classes to remain in session.

Though Penn's campus was less impacted than other areas of Philadelphia during the 1918 flu pandemic, the University canceled a number of classes and student group events in an effort to prevent the spread of the virus.

RELATED:

Penn Museum to remove Morton Cranial Collection from public view after student opposition

Penn Museum at Home offers virtual, interactive programs during closure

The 1918 flu pandemic subsided much quicker than today's COVID-19 pandemic. Quarantine lasted roughly one month, and Philadelphia and Penn resumed operations soon after.

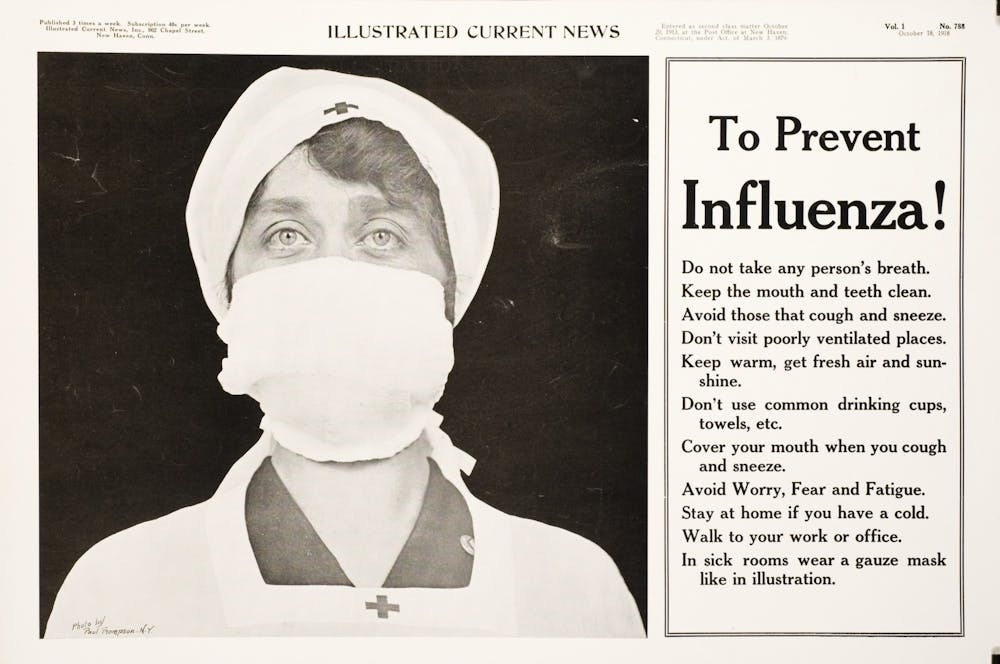

Hill said that drawing comparisons between the the 1918 pandemic and the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic is inevitable. Like today, she said masks were a preventative measure used 101 years ago.

The masks of the 1918 pandemic were made of gauze, were not highly effective, and Philadelphia did not institute a mask-wearing ordinance, as many other major cities including San Francisco did. Even so, Hill said the decision to wear a mask then was not as politicized as it is today.

“Group compliance was less of a personal liberties issue, and more of a kind of poverty and war support issue,” Hill said.

A sign at Philadelphia's Naval Aircraft Factory, where many had contracted influenza, in Oct. 1918. (Photo from the Mütter Museum of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia)

The 1918 influenza pandemic, caused by a strain of the H1N1 virus, disproportionately affected recent immigrants and first-generation Americans from areas such as Ireland, Italy, and Eastern Europe. Many of the recent immigrants lived in overcrowded row houses, where two or three families would share spaces meant for two or three people.

“Philadelphia was a very different place at the time,” Hill said. “It was an industrial powerhouse, and a lot of those industrial factories were making war industry supplies, so people couldn't work from home.”

Access to running water and sanitation also depended on financial standing during the 1918 pandemic. Hill said in some low-income areas, one outhouse was shared by an entire block. She added that today’s pandemic has revealed similar socioeconomic gaps in access to healthcare.

During the 1918 flu pandemic, large numbers of Black Americans died, while many doctors falsely believed that Black people were immune to influenza.

Today, Black Americans are dying from COVID-19 at three times the rate of white people nationwide. In Philadelphia, Black Americans make up just 40% of the population, yet they comprise 54% of Philadelphia's COVID-19 deaths. In April, false social media rumors surfaced that Black people were immune to COVID-19, echoing the sentiments of doctors from the 1918 flu pandemic.

Over 137,000 Americans have died from COVID-19 this year, compared to the 675,000 American deaths during the 1918 flu pandemic. However, COVID-19 cases are still on the rise in the United States, as many states still have not finished their first wave of infections while others have already begun to experience second waves.

Dr. Elizabeth Anderson, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Pennsylvania’s Hensley laboratory, wrote in an email to The Daily Pennsylvanian that people are "imprinted" with an immune response tailored to the influenza strain around them at young ages. Since different flu strains circulate over time, the antibody response imprint of someone born in 1950 looks very different to that of someone born in 1980, she wrote. This phenomenon is known as original antigenic sin.

Though Anderson wrote that there is a clear age cut-off at ages 65 or older for increased COVID-19 infection complications, she is interested in researching how original antigenic sin might apply to the current pandemic. Multiple seasonally circulating coronaviruses exist, but they are only distant relatives of COVID-19. More research is needed to determine if immune memory of these distant relatives might offer some kind of protection against COVID-19.

Hill said the COVID-19 pandemic has exposed a lack of scientific literacy in the general public, leading to a distrust of scientists who publicly change their stances upon receiving new information.

“People are not used to seeing science in real time,” Hill said. “They're used to reading about it in the past tense, so it's a little bit of something to wrap the head around.”

The Mütter Museum and its Spit Spreads Death exhibit will physically reopen on July 18. Only 50 people will be allowed in the building at a time, and the Museum will provide hand sanitizers to guests and require all visitors to wear masks.