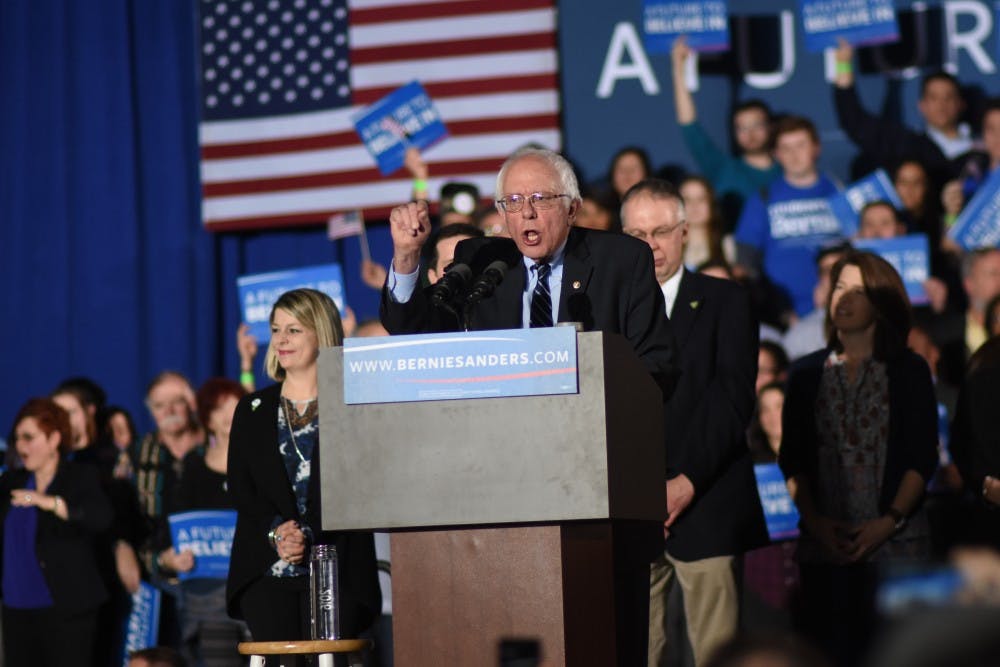

In the past months, Sen. Bernard Sanders (I-Vt.) has gained more political momentum in the Democratic presidential primary race than political pundits and the American public alike would have ever expected. The self-proclaimed democratic socialist has transformed himself into a legitimate rival to former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton by tapping into a disenfranchised electorate and calling for a political revolution.

While he has gained support for his consistent political convictions and sincere rhetoric, political opponents and critics have consistently questioned the political, financial and administrative viability of his proposed policies. Sanders has built his presidential campaign platform around the call to reduce income inequality, regulate Wall Street and increase access to health care and education.

Although the Vermont senator constantly cites other developed countries that have implemented the sort of left-wing social policies he advocates for, Penn experts are not so sure about the viability of implementing his public policy.

Wall Street Reform:

One of the cornerstones of Sanders’ platform is his call to reform Wall Street by breaking up the “too big to fail" financial institutions and putting a limit to systematic trading speculation. According to Sanders, three of the four largest financial institutions are 80 percent larger today than they were before the $700 billion taxpayer-funded bailout during the 2008-09 financial recession.

Most prominently, the presidential hopeful would reinstate the Depression era Glass-Steagall Act, which draws a line between investment and commercial banking. He would also set a cap on the size of financial institutions after ordering federal regulators to break them up.

Sanders would impose a 0.5 percent fee on stock trades, 0.1 percent fee on bonds and 0.005 percent fee on derivatives, per a CNN Money report. This new tax on Wall Street trading would raise up to $300 billion a year and would go towards funding tuition at public universities, according to a report authored by Sanders’ policy director, Warren Gunnels.

Many political observers have criticized Sen. Sanders’ regulatory plans as politically unfeasible if it meant passing his proposed legislation through Congress.

RELATED:

Bernie Sanders plays both preacher and therapist for N.H. crowd

Senator Sanders proposes making four-year colleges tuition free

“For most of those structural changes, he will depend on his legislative acumen to be able to drive these home. It is hard to see how he gets from point A to point B," said Peter Conti-Brown, an assistant professor of legal studies and business ethics. "Not only would he need to have Democratic majorities in both houses of Congress in order to succeed. You would need to have the kind of Democratic majorities that would be invulnerable to Republican challenges in the next elections."

Conti-Brown pointed out that one way Sanders could push his agenda is by appointing key allies in the Federal Reserve, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and other banking regulatory agencies. Although Sanders would still need legislation to reinstate a bill similar to the Glass-Steagall Act, appointment power at the executive level could produce new regulatory rules.

One of the more controversial debates among economists is how the economy and the financial sector would be affected if the largest financial institutions were to be broken up.

“Those that have supported Senator Sanders say it would unleash an enormous amount of economic productivity and that it would remove the drag on the economy that the big financial system has," Conti-Brown, who specializes in financial regulation research, said. “Opponents say that it would do the very opposite, that it would hurt companies ability to engage in capital formation to get the money they need and do the projects they want to do.”

There has also been much disagreement among experts on how much revenue a tax on financial transactions would generate. While Sanders’ team holds that it would generate $300 billion a year, a recent Tax Policy Center report found that it would only raise about $51 billion a year.

When crafting their numbers, Sanders’ team might have underestimated the amount of financial trades the tax would discourage, Conti-Brown said, thereby affecting their revenue estimate.

Single Payer Health Care:

Sanders is also committed to the implementation of a universal health care system. While he recognizes the successes of the Affordable Care Act, the candidate has proposed a single payer health care system to provide comprehensive coverage for all citizens.

Under the senator’s health care plan, patients would no longer need to worry about the health care provider they go to or about paying co-payments and deductibles, according to the platform on his website. Moreover, his plan would allegedly save patients and businesses over $6 trillion in the next decade and would cost an estimated $1.38 trillion per year.

To fund such a system, Sanders proposed an aggressive tax plan that would charge employers a 6.2 percent income-based health care premium and households 2.2 percent. The Vermont senator would also implement a more progressive tax system, limit tax deductions for the rich, implement an estate tax and tax capital gains and dividends.

Like the rest of the senator’s plans, his proposal for a universal health care system has received criticism because of how much it would expand the federal government, the challenges of administering such an expansive policy and how much it would actually cost.

Most recently, a report by Kenneth Thorpe, a respected health economist from Emory University, suggested that Sanders' plan would increase the size of the federal government by 50 percent and would cost almost double what the senator asserts.

Although Sanders consistently cites developed European countries with universal health care systems, certain critics question the administrative complexities of such a policy in a more populated country like the United States.

“Administratively, it is hard whenever you are doing something for 310 million people," said Ezekiel J. Emanuel, Penn's vice provost for global initiatives. "Changing things is difficult enough in Medicare, where you have 50 million people. When you have the whole country making a change, affecting everyone in the United States, it is a very different calculus there."

Emanuel, who is also chair of the Department of Medical Ethics and Health Policy at Penn, worked in the White House as special advisor for health policy when President Barack Obama’s administration was getting the Affordable Care Act passed in Congress.

The health care policy expert noted that Sanders' policy would eliminate the insurance market currently in place, mark the end of insurance companies and, probably, abolish Medicaid. Regardless of the policy’s complexities, Emanuel is certain that universal health care would be politically unfeasible.

“It is not going to get passed [in Congress]. We had no votes to spare for the Affordable Care Act," he said. "This is a more radical position. It is just not going to pass. There is no discussion here."

Making College Tuition Free:

To address the pitfalls of higher education in the United States and develop the best-educated workforce, Sanders has proposed making public colleges and universities tuition free.

Citing other developed countries which have done the same, Sanders plans on paying for this policy by imposing a tax of a fraction of a percent on Wall Street speculators. The proposed tax would allegedly generate the $75 billion a year necessary to fund his free tuition plan and assist college students with refinancing their student debt.

In the senator’s “College for All” plan, the federal government would pay $2 in matching funds for every dollar states spend on making tuition free at public colleges and universities, according to a CNN Money report.

Like the rest of his policies, skeptics doubt how palatable such a plan will be in Congress.

“At this point in time, I think [Sanders’ plan] would be dead in arrival. If he gets elected, he has to work with a Republican Congress, which is intent [on] reducing government expenditures, not expanding them," Joni Finney, professor of practice at Penn’s Graduate School of Education, said.

Even if such a legislation were to be enacted by Congress, Finney noted, there are still massive challenges and consequences of making public colleges and universities tuition free. Most markedly, Sanders would face the hurdle of centralizing a higher education system that is mostly run by state governments.

“It is really important to understand that states set public tuition and not the federal government,” Finney, who is also the director of the Institute for Research on Higher Education, said. “So Sanders will find himself in a position where he has to negotiate this 50 different times with 50 different states, which have 50 different types of higher education systems."

Finney said how, currently, state budgets aren’t allowed to incur budget deficits, yet implementing such an expensive higher education plan would probably require them to do so. Moreover, fully subsidized tuition at public colleges would pose competitive challenges for private, nonprofit academic institutions who currently charge high tuition rates.

“It would have a very negative effect on private institutions that are not selective. They would have a very hard time balancing their budgets and recruiting students,” she said. “It would draw more people into the public sector and increase the costs of the public sector."