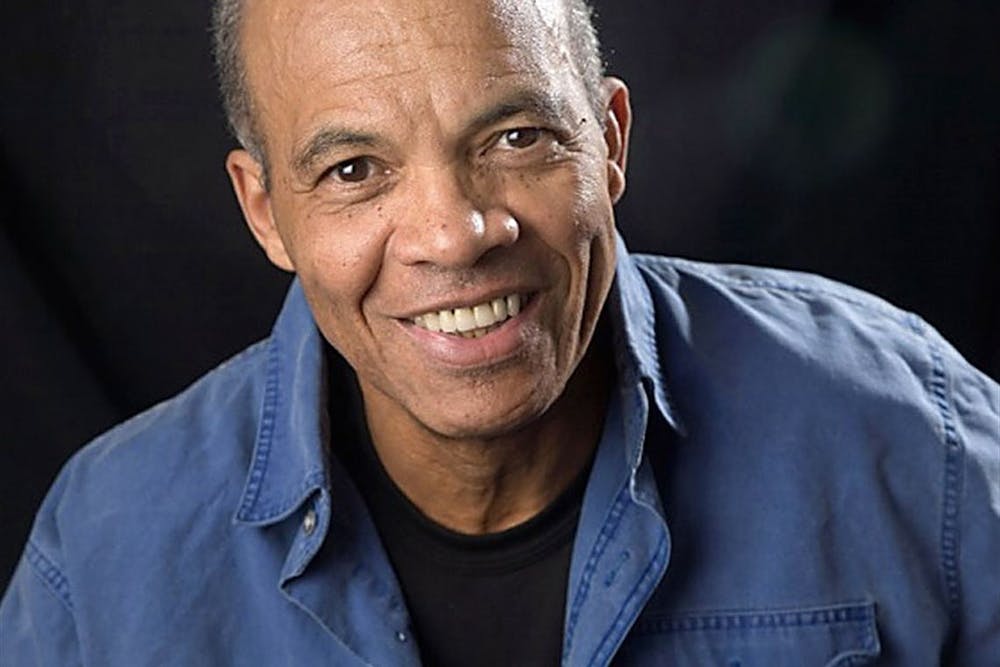

John Edgar Wideman broke barriers both during his time on Penn men’s basketball, as one of the few Black players on the team, and in his illustrious writing career that followed after he graduated.

The Pittsburgh native showed both academic and athletic promise from a young age. He was raised in the Black neighborhood of Homewood, and moved to Shadyside when he was 12. In high school, he was a star on his basketball team, served as student body president, and graduated as class valedictorian.

In 1959, Wideman received a Benjamin Franklin academic merit scholarship to attend Penn and was one of the few Black students in his class. In his memoir, Brothers and Keepers, he wrote about how he was motivated to excel in college by the thought of elevating himself out of poverty.

“I was running away from Pittsburgh, from poverty, from blackness,” Wideman wrote. “To get ahead, to make something of myself, college had seemed a logical, necessary step; my exile, my flight from home began with good grades, with good English, with setting myself apart long before I'd earned a scholarship and a train ticket over the mountains to Philadelphia.”

However, at Penn, Wideman grappled with an identity crisis. In addition to being one of the few Black students at the school, he was one of only two non-white athletes on basketball team. It's unknown whether Wideman was Penn’s first Black basketball player, but there are no Black players shown in any basketball team photos until he made varsity in 1961. He struggled with constantly being surrounded by whiteness and experienced alienating encounters with his white classmates.

The difficulty of assimilating and relating to his classmates took a toll on Wideman, and he even tried to drop out of Penn. However, basketball motivated him to continue. As he was about to board a train back to Pittsburgh, Wideman was stopped by his basketball coach, who convinced him to persevere.

Indeed, Wideman ended up excelling. He rose to the varsity team in his sophomore year. As an underclassman, he scored in the double figures several times during games. He became co-captain his junior year, and captain his senior year. As captain, Wideman led the team in scoring, and helped the Red and Blue to a 20-8 Ivy League record and a Big 5 Championship. Wideman's performance earned him first team All-Ivy status, and he was later enshrined in the Big 5 Hall of Fame.

Wideman was also recognized on campus for his writing, and was inducted into the Phi Beta Kappa national honor society. He graduated with a B.A. in English, and was the second Black person ever to be named a Rhodes Scholar, giving him national recognition. At Oxford, he studied 18th-century narrative technique. He became the first person in the world to win the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction twice.

RELATED:

Fighting racial injustice: From breaking color barriers to Black Lives Matter

Tracing Karl Racine's path from Penn men's basketball to D.C. Attorney General

However, as Wideman met tremendous success in his career, his family back home struggled. His brother was sentenced to life in prison in 1975 without the possibility of parole, though his sentence was commuted in 2019. Wideman's son was also sent to prison in 1986.

Wideman's literature focuses on his personal experiences, as well as the stories of his family that define his identity. The story of his brother's incarceration is a strong theme in his work. In his short story “The Beginning of Homewood,” Wideman intertwines his brother’s story with the story of his ancestors.

“I don’t have anybody living around me who has much of a sense of what I do,” Wideman told The New York Times. “That’s exactly what I like.”

Wideman has since taught at Penn and other institutions, and was one of Penn’s first Black tenured professors. Wideman, now 79, continues to write. He compares writing in his old age to playing basketball.

“By the time I finished playing basketball, I used to be, you know, the star, the go-to guy for whomever I played for,” Wideman told the New York times. “But at the end of the time on the playground, to make a layup, you know, to steal the ball once — it’s gravy. You don’t have to worry about carrying the team, your rep. You’re just out there, and anything you can get is good.”

Channeling the stories of his ancestors and his personal experiences as inspiration, Wideman has been able to persevere through struggles and share his Black experience with the world.