Clasping the rectangular bronze medal with his left hand — his good hand — as the blistering Paris sun beat down on his skin, George Orton felt sick to his stomach. Literally.

The Penn grad had just finished third in the 400-meter hurdles in the 1900 Olympics. A good finish by any standard, but he didn’t travel across the Atlantic Ocean by boat to settle for anything less than first place.

While he would later have a tremendous impact on Philadelphia and Penn Athletics, he was currently focused on a single goal.

He was determined to take home the gold in the 2,500-meter steeplechase, but he had a couple of problems: He was battling a dreadful intestinal virus, and the race was in just 45 minutes.

With barely any time to cool down from the hurdles, Orton toed the starting line at the old Croix-Catelan Stadium and waited for the deafening sound of the starter pistol.

Seven minutes and thirty-four seconds later, Orton powered through as the winner, the world-record holder, and the first disabled person to ever win an Olympic event — a fall from a tree at age 3 had left him unable to walk until he was 10 and permanently damaged his right arm, a disability that he managed to hide for most of his life.

He also became the first Canadian to win an Olympic medal. But, unfortunately for Orton, in a move that he would become all too familiar with, his medal was retroactively miscredited to the USA because he ran with Penn’s Olympic delegation. The mistake would not be corrected until noticed by a historian over 70 years later.

This was typical for Orton, as his accomplishments often went overlooked not only in Canada, but have now been largely forgotten by Philadelphians, and his legacy has not been honored.

RELATED:

125 years of Franklin Field: The birthplace of Penn Relays

Breaking the Ice: Why doesn't Penn have varsity ice hockey, men's volleyball?

Although the Strathroy, Ontario native held seven national titles, the Canadian press barely acknowledged his existence, and virtually nobody in Canada knew about his medal.

“He’s part of a history that predates the glory days of professional sports,” said Mark Hebscher, author of "The Greatest Athlete (You’ve Never Heard Of): Canada’s First Olympic Gold Medallist," the first and only book to date written on George Orton.

“If he had been around today, he definitely would have been an absolute superstar.”

Fresh off a victory in the races at the Chicago World’s Fair, Orton came to Penn in 1893 to pursue graduate degrees and began to make a name for himself in the states as he took on Philadelphia as a second home.

As captain of the Quakers’ track team, he was a seven-time All-American. While completing his Ph.D. in philosophy, he ran in the first Penn Relays in 1895, an event for which he would later become the director, becoming the natural successor to Frank B. Ellis.

Although he was well known and respected in his time, he is not memorialized at all at Franklin Field, a venue whose towering reputation he helped build, as he set numerous records, coached Penn track, and oversaw the Penn Relays as the event became one of the premiere track meets in the world.

But his contributions to Philadelphia athletics went beyond track and field.

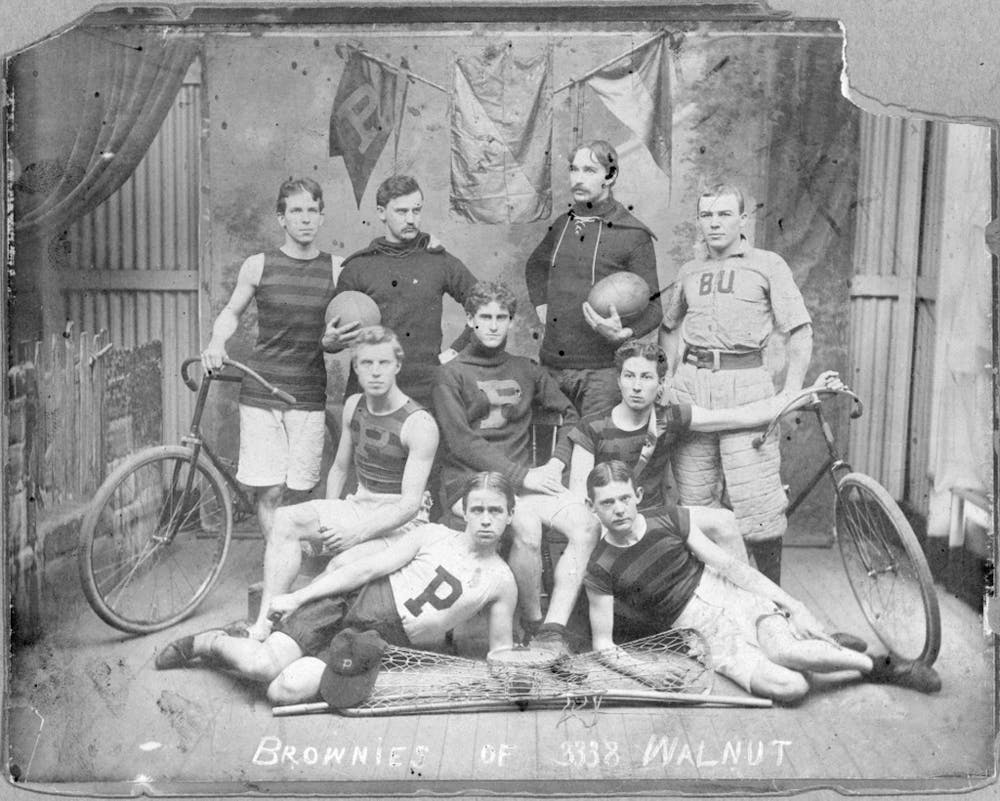

As a Canadian, Orton was an avid hockey fan. In the 1890s, most Philadelphians had never heard of the sport before — let alone played it. Orton, however, was a prolific player despite his disability, so in 1896, he brought the sport to his new city and founded Penn ice hockey and captained its first team.

Seeing that the school did not have a proper facility, he oversaw the construction of the first indoor ice rink in Philadelphia, West Park Ice Palace on 52nd and Jefferson, and the popularity of the sport grew from there.

When Philadelphians reflect on their hockey heroes, George Orton rarely comes to mind. Many will mention Bobby Clarke, Bill Barber, or Bernie Parent, but those stars may have never shined if not for the man who was known in his time as “The Father of Philadelphia Hockey.”

After his athletics career ended, Orton authored several books on cross country, helping to revolutionize training methods for years to come. In his free time, he also wrote a book on the history of Penn Athletics.

He served as the city’s athletic commissioner, founded the Children's Playground Association in Philadelphia, and was headmaster at Banks Preparatory School, where he used his ability to speak nine languages to teach language arts.

He was also an early adopter of basketball in Philadelphia, has been credited with igniting the Philadelphia-New York sports rivalry, and was the first high-profile proponent of putting numbers on college uniforms to make it easier for fans to see.

And he was the manager of Municipal Stadium — later JFK Stadium — and was responsible for bringing the Army-Navy game to Philadelphia, an important event that still regularly attracts sitting U.S. presidents.

Although most of his greatest contributions came nearly a century ago, they still have a great impact on the current Philadelphia sports landscape. But, today, he’s totally forgotten.

There are virtually no plaques, statues, or namesakes to be found honoring him in a city filled with memorializations. One of his only commemorations in the city is his spot in the Philadelphia Sports Hall of Fame, but he wasn’t inducted until 2016, and the website uses a picture of his brother instead of him.

His memory has not been treated much better in his native land.

On the 120th anniversary of his Olympic triumph just last week, the Canadian Olympic Association honored him with a now-deleted tweet that also used a picture of another man. On the same day, The Globe and Mail, one of Canada’s most read and reputable newspapers, printed an article about him filled with multiple factual errors, including saying that he was from the wrong home town.

“This poor guy has been misidentified, misunderstood, and ended up in history’s dustbin,” said Hebscher. “Man, you have to feel for someone like that, who had those kind of accomplishments but just has been completely ignored, overlooked, and forgotten.”

Looking to set the record straight on Orton, Hebscher was inspired to write his book because of how the athlete had been mistreated by history.

Despite his accomplishments, the legend of the Canada native has been mostly lost to time. Although George Orton lacks the name recognition of others, his success was undeniable and his impact was dramatic.