This summer, I am cataloging and digitizing some of the letters sent to Samuel George Morton, the founding father of race science, whose research bolstered the antebellum pro-slavery movement. My exposure to his collection of crania, housed in the Penn Museum’s Center for the Analysis of Archaeological Materials labs, has made it abundantly clear that the Museum keeping the crania of the Morton collection is racist, oppressive, and a violation of basic human rights.

When slavery was rampant in the American South, Morton was researching at Penn, an institution whose founders relied financially on slavery. Morton claimed that slavery was justified because cranial capacity reflected mental capacity, and his research showed that people of color, most drastically Black people, had a smaller cranial capacity than white people. He measured cranial volume by filling crania first with seeds, then with lead shot, and averaged the ranges of data to represent the cranial capacities of each entire race. By taking averages of cranial volume by race, Morton obscured the fact that all of the crania, regardless of race, shared similar volumes.

Morton’s cranial collection was shipped to him by a network of friends and colleagues scattered throughout the globe, often to curry favor with Morton and the Academy of Natural Sciences, where the collection resided. The crania were often stolen from graveyards and battlefields — from the land and people where they belong — sometimes in dozens.

After Morton’s death, the Academy held onto the collection of 918 crania for some years. In that time, the collection grew to 1,355. In 1966, the Penn Museum obtained the collection, and it now remains in its basement in “open storage.”

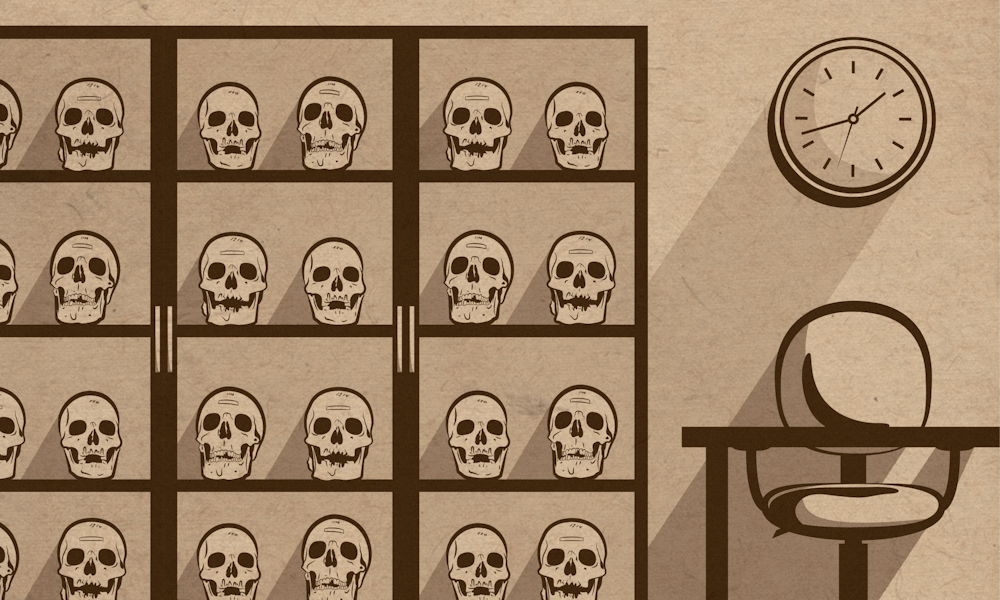

“Open storage” in this case means that about half of Morton’s collection is displayed openly in glass shelves in classroom CAAM 190 in the Penn Museum, and many crania in that room are visible from the hallway through the glass door. Fourteen separate introductory and advanced courses have been taught in the room in the past three years, including five in Fall ’19 and six in Spring ’20. Recitations are also held in that room, tests are proctored there, and high-school classes have visited, as well.

I spoke with rising College senior Susan Zare, an anthropology major and archaeology minor, who took three courses satisfying major requirements in that room. In the two upper-level courses, none of the crania were addressed. In the lower-division class, the collection was mentioned, but the presence of crania of Indigenous and enslaved people in the room wasn’t acknowledged. Further, no one ever explained why the crania had to be on display in a classroom. Zare added that she didn’t feel comfortable in that room, and would sit where the collection wasn’t visible, but her discomfort only made her want to learn more about the collection.

But who, precisely, makes up this collection? I say “who” because it shouldn’t be forgotten that these crania are human beings. Many were brutally exploited by colonialism when they were alive, and now they rest in a predominantly white institution. A person’s right to decide where they rest after death is not only a fundamental human right, but it is our agency.

Of the crania in the collection, 53 were enslaved people, most of which are on display in CAAM 190. Fifty one were abducted and sold into slavery in West Africa in their lifetime, broken and dehumanized in the Atlantic, and killed in the Caribbean. Then, they were decapitated post-mortem in Havana, Cuba. Much of the Morton collection consists of Indigenous crania from the Americas. These people are on display in the basement of a predominantly white institution, row upon row, in glass cabinets marked with numbers and labels such as “idiot,” “lunatic,” and “negro” directly on their foreheads.

The same enslaved Africans whose agency was ripped away from them in the most brutal way were used as scientific tools by Morton to promote enslavement and oppression. Not only have all these people been treated as objects, they have been misused as instruments to further the subjugation of their descendants. The agency of these people is their right. Their suffering has been ignored. And the ignorance most people on campus have about their history, about the people who remain trapped beneath their own feet, is atrocious.

The Penn Museum has no right or reason to keep human remains that bolstered racist science in its basement. Over the years, researchers have measured the collection to uphold Morton’s findings, used data of the crania online on the Open Research Scan Archive to conduct their own research, and professors have taken classes to see them in person — actions that have served as justifications outweighing the moral cost of retaining the crania and for the Museum to avoid repatriating most of the collection.

The Museum should follow the lead of Police Free Penn, one of the latest groups calling for the immediate repatriation and burial of the crania in the Morton collection, alongside the Penn and Slavery Project. In accordance with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, in 2008, the Museum already repatriated about 100 Native American crania from the collection. However, NAGPRA is limited to only federally-recognized tribes within United States borders. These repatriation efforts should be expanded to the entire collection. Further, ORSA should at the very least include a disclaimer acknowledging and disclosing the unethical origins of its data and delete rationalizing remarks about the effect of Morton’s racist science.

Until then, the crania should be moved out of CAAM 190 and into closed storage with the Indigenous crania subject to NAGPRA. These people belong with their descendants. They belong in their homelands. Finding those descendants will, no doubt, be a daunting task, but one that must be endeavored, nonetheless.

GABRIELA PORTILLO ALVARADO is a rising College sophomore from Sacramento, California, intending to study Health and Societies, Latin American/Latino Studies, and Hispanic Studies. Their email address is alvga@sas.upenn.edu.