The AIDS Memorial is a digital archival project that features portraits of famous and everyday LGBTQ+ identifying — mostly gay men — who died during the peak of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, from approximately 1981 to the early 1990s. Yet, perusing this Instagram account (one of Anderson Cooper’s favorites, I might add) feels more like touring a museum exhibit than scrolling through a social media timeline. The mostly black-and-white photographs are brought to life by vivid anecdotes and intimate tributes penned by the friends, family, and former significant others of those commemorated.

The collection tells the story of a time when HIV was a mystery to researchers. Given the advent of today’s life-saving treatments for HIV, many millennials like myself can hardly fathom the uncharted course of the early epidemic that the AIDS Memorial documents. The night that I stumbled across the gallery, I spent two hours in awe that the faces staring back at me had paved the way for today’s global movement to find a cure for AIDS. Before logging out, I even scrolled down the entire timeline once more. Then, suddenly, my racing thumb came to a screeching halt.

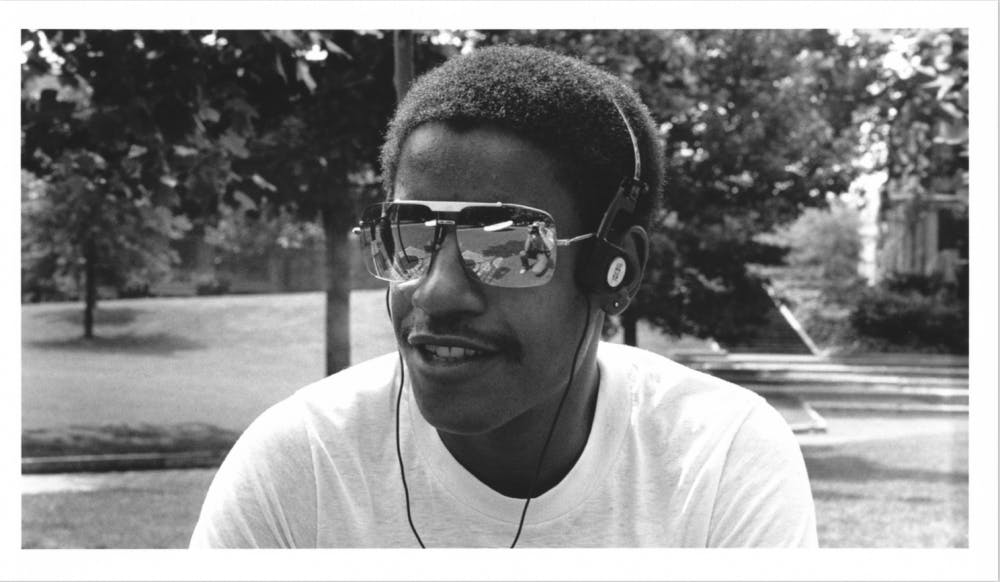

In the backdrop of a black-and-white photo from the early 1980s, I recognized a place that I affectionately call my second home. The caption reads: “This is Paul Whitedy who worked at the [University of Pennsylvania] library, where I met him. Four years from this photograph, he would die of AIDS. He would be my first friend to die from AIDS, but I wouldn’t know that for a few years after his death. Friends disappear all the time in gay life, and at the time, AIDS was a private shame to many families.” Arthur Bruso, an artist and curator, penned the tribute and submitted Whitedy’s portrait, which he had taken during his years as a graduate student.

During my own tenure as a graduate student at the University, I had passed by the exact location of the photo, right outside of Van Pelt Library, almost daily. Once, I had even posed for a picture on a bench in the very same spot where Paul is sitting. It was that eerie similarity between the capture of Paul and myself that had startled me.

Reflecting upon my time as a queer, Black Penn student, I stared at Whitedy’s portrait, amazed. I intuited the part of his truth that his cheerful countenance masked. I contemplated how disempowering it must have been to face the same challenges I did, during a time when the campus community was even more homogeneous and less inclusive, and when the stigma of HIV and AIDS was at its worst.

In 2016, I graduated from Penn, having earned the Award for Excellence in Promoting Diversity and Inclusion. But no accolade for social justice could erase the memories of being heckled with homophobic and racist slurs by men looking down at me from the balconies of fraternities on Locust Walk; or, conversely, feeling underrepresented and sometimes ignored in both the Black and LGBTQ+ communities. While these very same disempowering experiences compelled me to forge my own path and cultivate a sense of belonging for myself, I still felt the pangs of invisibility and exclusion.

Studying Whitedy’s portrait, I wondered, “How much more strength did it take for him to affirm his worth, especially in the face of the flagrant stigma and overwhelming grief that characterized the early days of the HIV/AIDS epidemic?”

In a recent conversation with Derek Lamont Walker, a friend, activist, and survivor of the early part of the AIDS epidemic, Walker recounted, “It was as if all of my friends and I were in a large sealed room that someone tossed a hand grenade in, and myself and a few others were the only survivors. Having experienced such concentrated suffering and loss, it is a wonder that all of us survivors have not gone mad.” Like Walker, most gay men who came of age during the 1980s and 1990s can name dozens of gay friends who died of AIDS.

Many survivors’ stories evoke the imagery of bodies "dropping like flies" to illustrate the bewildering rate at which gay men seemed to suddenly fall ill and then disappear from gay social life. They remember the way in which the epidemic coincided with the emergence of gayborhoods in cities like New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco, leading the media to perpetuate the misconception that HIV/AIDS was a “gay disease.” They remember friends who spent months and years hospitalized, without a single visit from relatives who abandoned them. They remember checking the obituary section of local and national newspapers quite regularly.

To this day, the generational trauma still reverberates within the gay community, with today’s young gay men lacking elders and mentors because of the “lost generation.” And just as gay Black men like Whitedy were at the highest risk during the 1980s and 1990s, the HIV/AIDS epidemic still disproportionately impacts today’s younger generation of gay Black men, with the rate of diagnosis among gay Black men being one in two. Even in the Ivy League, this racial disparity exists — which is exactly why the the University of Pennsylvania should feel obligated to commemorate Paul Whitedy.

Whitedy’s presence is a reminder that the University of Pennsylvania is simply a microcosm of larger society, albeit a a community that strives more than most others to stand for equity. Contrary to popular belief, the campus bubble does not shield everyone from our country’s continued legacy of structural inequity. While the ivory tower may afford one unmatched professional and scholarly opportunities, no academic institution, regardless of how elite or well-resourced it is, can separate itself entirely from the outside world. No one expects gay, HIV-positive Black people, like Whitedy, to be denizens of the Ivy League. But they are there, and they always have been.

Araya Baker is a counselor educator, suicidologist, and policy analyst. Baker holds a M.Phil.Ed. in Professional Counseling from the University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Education and an Ed.M. in Human Development & Psychology from the Harvard Graduate School of Education. You can follow Baker’s work at arayabaker.com.