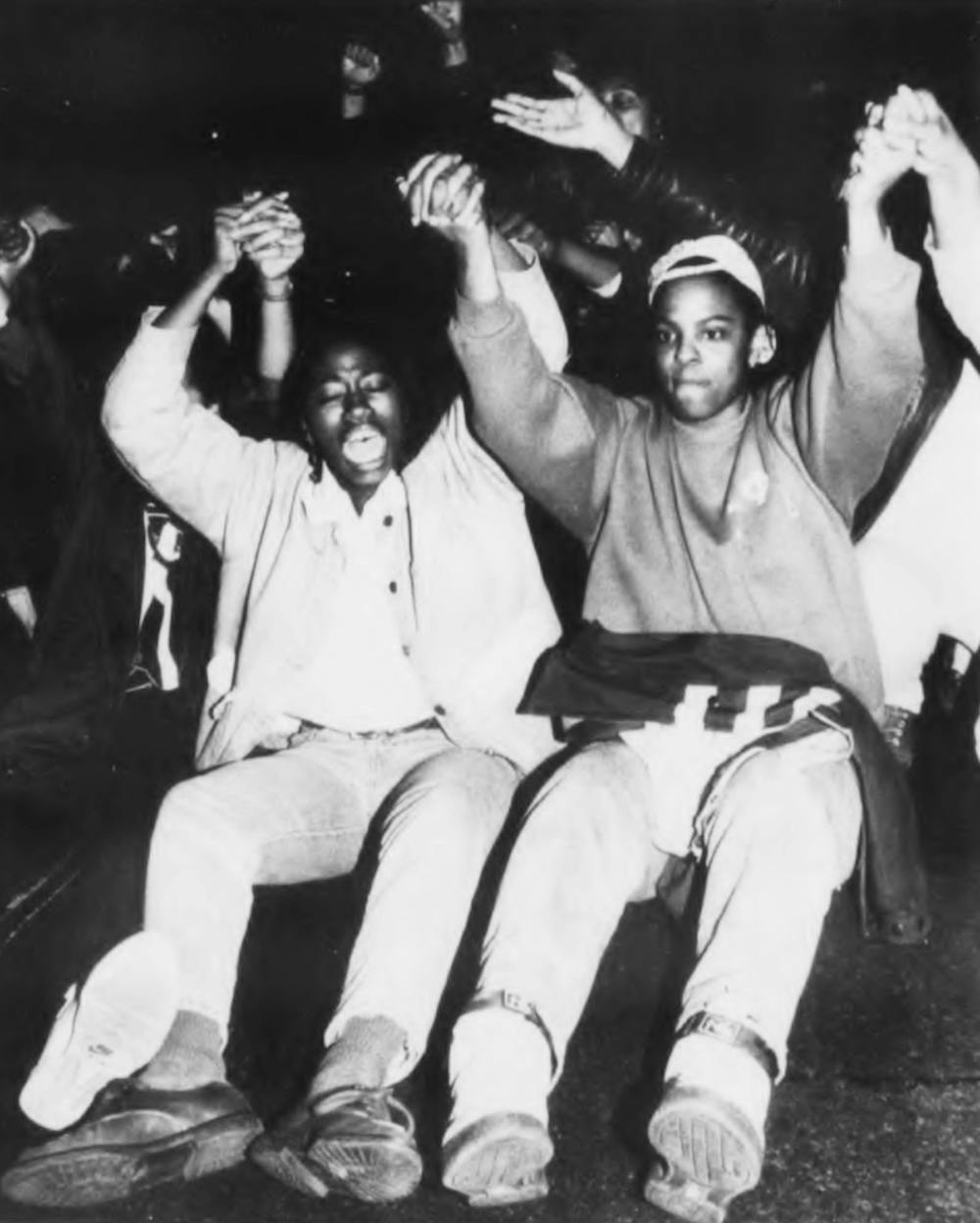

T h e crowd grew by the hundreds, accumulating outside of Penn President Sheldon Hackney’s campus house, the protesters chanting for him to come out and meet them face to face. It was April 1992, and students had stormed down Walnut Street alongside Philadelphia residents to call for an end to the racial discrimination that had plagued the country for centuries. Like countless others across the nation, the protest erupted after the brutal beating of a black man named Rodney King.

Hackney watched the crowd through the windows of his house with his chief of staff, Linda Wilson. Finally, he decided to walk outside.

“It looked threatening,” Wilson said in an interview this month. “All you could see was people. And Dr. Hackney just looked at them and said, ‘Well, I’m going to see what I can do.’”

Into the early hours of the next morning, Hackney listened to the frustrated students who had compiled a list of the many ways the University had made black students feel unwelcome. They urged Hackney to institute diversity training seminars for all Penn faculty members and police officers — what the students considered a small, but tangible step in the nationwide fight for racial tolerance.

Many Americans argue that racism is still a potent force in society and call for its eradication — a goal that history has shown is dishearteningly difficult to achieve. But for decades, Penn students have used the University as a starting point in the battle.

A legacy of protest

On the evening of Oct. 25, 1981, W.E.B. DuBois House receptionist Jackie Brown received at least eight threatening phone calls from someone who asked her if she “liked dead niggers.” Two days later, in a rally organized by Vice Provost for University Life Janis Somerville, an unprecedented 1,000 students, faculty members and administrators linked arms and formed a circle around DuBois, singing “We Shall Overcome.”

From the late 1960s through the 1980s, Penn served as a microcosm for the tumultuous race relations that engulfed the United States in the aftermath of the Civil Rights Movement. But the calls for peace by administrators and students that followed each incident over the years weren’t enough to end the discrimination that black students had faced.

A national leader in the fight for racial justice, W.E.B. DuBois worked at Penn while conducting research for his 1899 study “The Philadelphia Negro” and became one of the school’s first black faculty members. In his honor, Penn renamed a residence hall in 1973 to W.E.B. DuBois House and began a living-learning program that taught and discussed African-American history. The building, once called Low Rise North, is Penn’s only predominantly black residence hall.

Since the inception of DuBois House, residents have been the targets of racially motivated death threats, testing Penn’s ability to respond to widespread panic and protests over racial confrontations.

In a statement from Hackney and 21 other Penn officials at the time of the threatening phone calls, the University condemned racial harassment and called for tolerance. But a week later, The Daily Pennsylvanian received phone calls from someone threatening to kill the chair of the Undergraduate Assembly and the president of the Black Student League, who were both black students. The perpetrator was never discovered, and the administration did not take any further action to protect students from racial threats.

Black students launched one of their early protests over racial discrimination in 1979, after Kappa Sigma brothers wore Ku Klux Klan robes to a costume party. Campus tensions had already been high following an incident just a month earlier when Kappa Sigma brothers had accused the wrong black man — a Penn administrator — of stealing one of their bikes. They threatened the man, holding up a crutch as a weapon, before realizing the error.

In response to the incidents, about 75 black students marched to College Green and called for Penn to revoke Kappa Sigma’s recognition. The University met the demand in February of the following year, but the decision was reversed two and a half months later after outrage by Penn students who called it unfair retaliation.

Despite the setback and the perception that the University dragged its feet on addressing discrimination, the protesters have kept up the pressure.

“Students are still aware of larger inequities in society and they come from a tradition of resistance,” said Associate Vice Provost for Equity and Access William Gipson, who served as the University Chaplain from 1996 to 2007. “Everything from the slave insurrections to the work of Dr. King is part of that tradition.”

Tensions flared up again in February 1985, when Wharton lecturer Murray Dolfman called five black students “ex-slaves” in class and asked them to recite the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments from memory. Students organized a sit-in that interrupted Dolfman’s legal studies class and a 200-student occupation in Hackney’s office to protest “the administration’s lack of sensitivity to black students,” the DP reported at the time.

The University responded with a statement that stressed its commitment to a “strong and vital black presence at Penn.” Hackney demanded an apology from Dolfman, who was suspended for a semester, but critics were disappointed that the administration made no policy changes to prevent similar incidents in the future.

Provoking dialogue

The early 1990s saw a constant flow of racial harassment incidents at Penn, drawing even more criticism to the administration and stirring a national media frenzy.

The spark that lit the fire was just five words: “Shut up, you water buffalo.”

Then-freshman Eden Jacobowitz yelled the words out of his wind ow in January 1993 to a group of rowdy, mostly black sorority sisters. Perceiving the statement as a racial slur, Penn charged Jacobowitz in the student judicial office for violating the University’s racial harassment policy.

Jacobowitz remained adamant that “water buffalo” referred to a Hebrew slang word and contained no racial underpinnings. Jacobowitz, a 1995 College graduate, could not be reached for comment for this article.

Shortly after what became known as the “Water Buffalo incident,” self-described “members of the black community” stole 14,000 copies of the DP to protest an allegedly racist columnist and the DP’s alleged lack of appropriate minority coverage. The administration was slow to act in response to the thefts, leading to vicious attacks against Hackney in the national media for his supposed preference toward minority students and his failure to protect free speech on campus.

“The language police are at work on the campuses of our better schools,” NBC news anchor John Chancellor broadcast at the time. “The culture of victimization is hunting for quarry. American English is in danger of losing its muscle and energy. That’s what these bozos are doing to us.”

The ordeal, which began shortly after President Bill Clinton nominated Hackney to head the National Endowment for the Humanities, led to intense dialogue on campus about the administration’s policies concerning race.

“I remember having lots of conversations around the issue,” Leo Greenberg, a 1996 College graduate who lived down the hall from Jacobowitz during the Water Buffalo incident, said in an interview this month. “But then, in less diverse circles, I’m not sure whether it prompted more discussion or whether it just prompted more animosity.”

Before long, the conversation spiraled into chaos as television reporters camped out on campus and dubbed Penn as the prime example of political correctness run amok. The affair garnered interest from all corners of the country, including Clinton’s office.

“The White House was calling up and saying, ‘Can’t you put a lid on this thing? We don’t need this now, we’re trying to get your confirmation through,’” Wilson, Hackney’s chief of staff, said. “No, you couldn’t put a lid on it. You couldn’t make it stop. You couldn’t make it go away. It really took on a life of its own.”

The sorority sisters began receiving anonymous postcards: “Water buffalo have brains. You do not. Niggers do not have brains,” one read. “What an insult to the water buffalo. You are a black ass nigger,” said another. Ultimately, the women dropped the case against Jacobowitz, believing media bias would make a fair hearing impossible.

With campus hostility in the back of his mind, Greenberg wrote a political science paper in his sophomore year outlining the extent of racial segregation on campus and presented it to the UA. In 1994, 80.9 percent of DuBois students were African American — the highest percentage of any ethnic group in a single dorm — even though African Americans made up just 7 percent of the campus population. They constituted only 1.8 percent of the Quadrangle, the largest dormitory on campus.

Greenberg proposed that the University institute randomized first-year housing to address the segregation. What he didn’t know was that he had resurfaced a longstanding controversy that remains unsettled even today. From the time DuBois was formed, civil rights activists recognized that its living-learning program attracted an unrepresentative number of black students. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People even threatened to sue the University for promoting racial segregation.

“It just seemed sort of staggering that people were collecting homogeneously,” Greenberg said. “But then again, there’s two varying schools of thought ... it’s somewhat disenfranchising to minorities who have a valid interest to protect their identity.”

Even after the proliferation of organizations for minority students — like UMOJA and the Greenfield Intercultural Center — exactly half of DuBois residents self-identified as black in the fall of 2013, according to College House and Academic Services statistics. Black students still constitute only 7 percent of the Penn undergraduate population.

Coming to Penn for some black students is a “culture shock” that can make them feel unwelcome in spaces on campus with predominantly white students, said Wharton senior Nikki Hardison, political chair of UMOJA — the umbrella organization for black student groups.

“Sometimes there’s trepidation that we won’t be welcome into those spaces. That those spaces are non-minority spaces,” Hardison said. “You need to be able to have a place on campus where you can go and know that you will be understood and that you’re not being judged.”

‘The highest standard’

Since the turn of the millennium, the number of documented incidents of racial harassment at Penn has dropped, but students and administrators say that the fight to end discrimination on campus — as well as around the country — is far from over.

“I think it behooves us being one of the major universities — major research universities — to pay attention to unconscious bias,” said Gipson, the associate vice provost, who has been the faculty master in DuBois since 2006. “Even though we think we’re open-minded, we use bias, this survival tool, to make quick judgments about the situations we might be in. And there’s nothing inherently wrong about that, except when you see the impact of that bias in the context of racial hierarchies in this country.”

But how to ensure that minority students feel comfortable on campus and how to diminish “unconscious bias” remain hotly disputed. Periodic incidents of racial harassment continue to crop up, reminding students of the progress yet to be made.

In 2011, College of Liberal and Professional Studies student Christopher Abreu wrote an op-ed in the DP discouraging black students from attending Penn. He came to the conclusion, he wrote, when a group of drunk Penn students asked him where to find fried chicken and called him a “nigger.” The next day, 200 students, along with Penn President Amy Gutmann, gathered for a silent protest on College Green.

“Each of us has a responsibility to cultivate mutual respect in both word and deed, every hour of the day and every day of the year,” Gutmann wrote in a published letter to the DP the following day. “Is this a high standard? No. It is the highest standard, set because our community deserves nothing less.”

Protests, rallies and sit-ins continue to crop up every few years following racially charged incidents on campus and nationwide. The hope, organizers of such events have said, is to tackle the national issues of racial discrimination by first working on them on a smaller scale at places like Penn.

“At Penn, you’re able to pull from a very diverse group of intellectual individuals who have a stake in making sure there is change, because it’s the world they’re ultimately inheriting,” said College senior Kyle Webster, president of Onyx, a senior honor society for black student leaders. “So it’s almost like, ‘I’m going to face this problem tomorrow, so why not solve it today?’”

When a neighborhood watch coordinator shot and killed unarmed black teenager Trayvon Martin in 2012, 200 students and Philadelphia residents marched from DuBois to LOVE Park, hoping that raising awareness could help prevent similar incidents. But a similar incident came this summer, when Michael Brown, another unarmed black teenager, was shot and killed by a white police officer in Missouri.

This time, more than 120 students attended a town hall meeting in Irvine Auditorium to discuss how to combat racial discrimination at Penn, in Philadelphia and

around the country. Students proposed the creation and distribution of pamphlets outlining rights for individuals approached by police officers and advocated for legislation to minimize use of excessive force. But, as the test of time has convinced many student leaders, it may be a while before progress is made.

“In my four years here, if I see one change, that would be almost a miracle,” said Wharton senior Justin Malone, president of the Black Student League. “But at the end of the day, you keep fighting because you realize that if you stop, other people may stop, and that’s just only going make the move toward progress that much slower.”

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

DonatePlease note All comments are eligible for publication in The Daily Pennsylvanian.