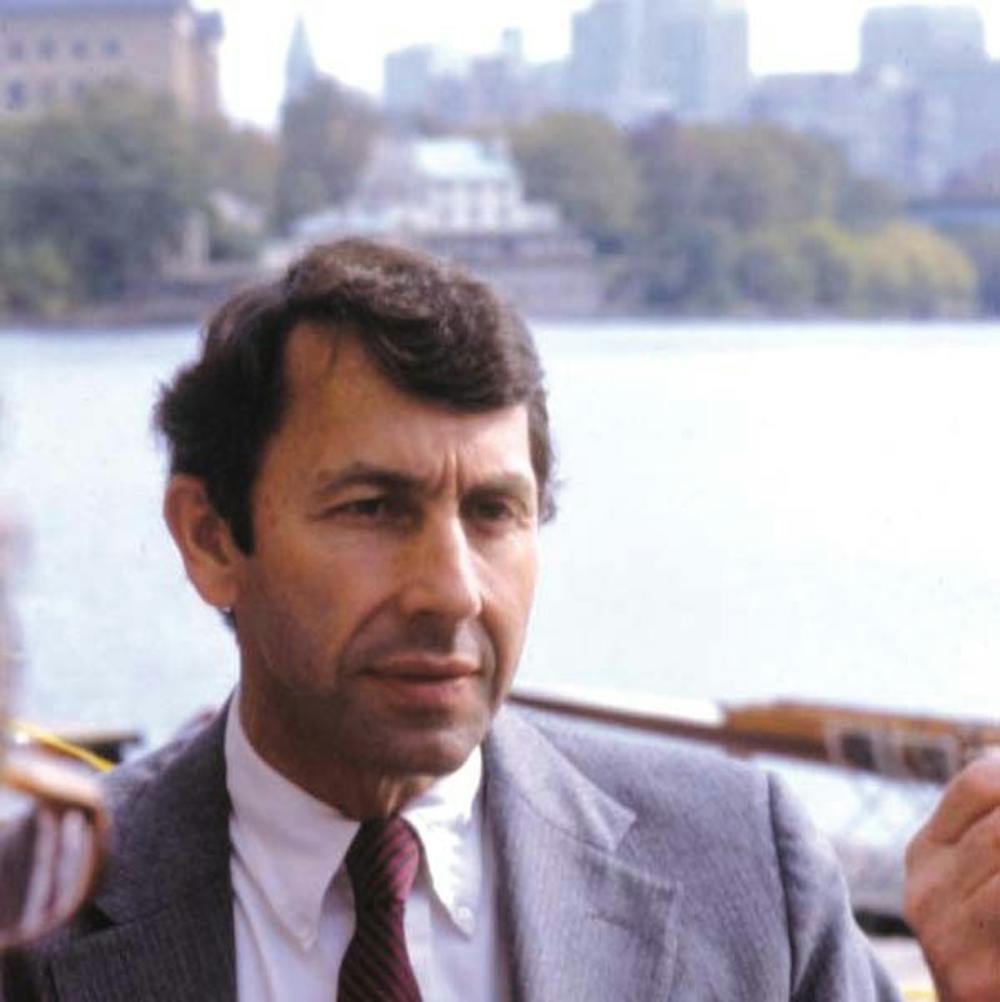

Former University President Sheldon Hackney died of Lou Gehrig’s disease in his home in Martha’s Vineyard.

Credit: Courtesy of University ArchivesSoon after Ed Rendell was sworn in as mayor of Philadelphia in 1992, then-Penn president Sheldon Hackney went to see him in City Hall, a bold plan in hand.

Hackney, who took office in 1981, had spent much of his presidency trying to repair the University’s unsettled relationship with its West Philadelphia neighbors. Penn, in its push to expand westward before Hackney came on board, had angered much of the surrounding community, some of which had been displaced by the University’s growth.

Penn’s future, Hackney told Rendell and David Cohen, the mayor’s then-chief of staff, no longer laid west of 40th Street. It laid to the east.

The plan was ambitious at the time — “probably a bit unrealistic,” Cohen, now the chair of Penn’s Board of Trustees, recalled — but the pieces were in place for the University to extend its reaches toward the Schuylkill River.

Most now credit the administrations of Judith Rodin and Amy Gutmann with planting the seed for Penn’s eastward expansion, but it was Hackney, former colleagues say, who first had the idea to connect the University with Center City.

“Sheldon had this idea way before anybody else was even thinking about it,” Cohen said of Hackney, who died at his Martha’s Vineyard home last Thursday following a brief battle with Lou Gehrig’s disease. “It’s a very good example of the vision that he demonstrated, the willingness to dream that he brought to his presidency.”

RELATED: Under Hackney, a university met a community

One of Penn’s earliest forays east of 34th Street came in 2007, when it finalized a deal with the U.S. Postal Service to purchase the 14-acre parking lot that would later become Penn Park. The deal, which also included an old post office building and a truck terminal annex, cost the University $51 million; four years later, in the fall of 2011, Penn Park opened.

In the early 1990s, when Rendell listened to Hackney present his long-range plan, the former mayor responded with a question: Was the Postal Service even selling?

“Not at the moment,” a smiling Hackney said during the meeting, according to Cohen, “but we never know what might happen.”

“Sheldon realized that, on so many levels, you couldn’t do a project like this without the help of the city,” said Rendell, a 1965 College graduate and former Pennsylvania governor. At the time of the meeting, Rendell said, Hackney was looking to lay the groundwork for a public-private partnership between Penn and Philadelphia.

“His plans were pretty consistent with what I’d envisioned — finding a way to get more of our universities connected with the city, and in particular trying to link Penn more closely with Center City,” Rendell said.

RELATED: Remembering Sheldon Hackney

Hackney brought a map with him to the meeting, in order to show the mayor and his chief of staff what Penn’s campus might look like years down the road. Hackney, who left Penn the following year, knew that the goal of expanding eastward would likely never come to fruition under his presidency, but he nonetheless wanted people at Penn to start thinking about it as part of the University’s future.

“He was a big-picture person,” Mark Frazier Lloyd, director of the University Archives and Records Center, said. Lloyd was appointed by Hackney. “He had the sort of long-range vision beyond just his own presidency that you want the leader of any major institution to have.”

The little-known story of Hackney’s pitch to Rendell and Cohen, Executive Vice President Craig Carnaroli said, is also a sign that the former president recognized what lasting damage could be done if the University continued expanding westward. Purchasing land to the east, Carnaroli said, was an ideal way to avoid re-aggravating any of Penn’s problems in West Philadelphia, while at the same time continuing to increase the size of the campus.

Today, much of Penn’s expansion to the eastern side of the Schuylkill River, one of the top priorities inside College Hall, is taking place at the South Bank. Penn purchased the South Bank property, which is located on the southern bank of the Schuylkill at the intersection of 34th Street and Grays Ferry Avenue, from the DuPont Company in 2010. In the future, the University envisions the South Bank playing a major role in expanding its technological innovation ventures — particularly by opening the door to partnerships with startup companies that are looking to find space and grow.

Earlier this semester, Gutmann announced plans to create a “Pennovation Center,” a site that will be a hub for innovation and research, at the South Bank.

A new college house on Hill Field , as well as the Singh Center for Nanotechnology on the 3200 block of Walnut Street, are also parts of the University’s plans to expand to the east. The Singh Center will open later this semester, and the Hill college house is expected to open in the fall of 2016.

“Sheldon was really the foundation for all of these projects,” Cohen said, “and you can’t do anything without the foundation.”

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

DonatePlease note All comments are eligible for publication in The Daily Pennsylvanian.