When junior Colin Donnelly suffered his fifth concussion, he knew it might be time to end his days playing football.

It happened early in his sophomore season during a JV football game and came just weeks after his fourth.

Given Donnelly’s history of head injuries, football trainers sent him to see a neurologist for further examination.

“I took the test a week after that last concussion,” Donnelly recalled. “[The doctor] thought my testing was a little inconsistent.”

With the uncertainty surrounding head injuries, his doctor advised Donnelly to stop playing so that he could successfully take advantage of his rigorous Ivy League education.

For Colin, stepping down from the team was a “no-brainer.” Whether he would have been cleared to ever play again by the doctors, he doesn’t know. But he decided to hang up the cleats. His coaches were supportive.

However, ending his collegiate football career didn’t halt the effects of his concussion. For weeks after the hit, Donnelly struggled with schoolwork — a challenging hurdle for a Wharton sophomore.

“Doing work was hard,” he said. “I would get headaches when I would focus, when I would read. Class was pretty much the same thing.”

Colin added that in the weeks after his concussion, he had trouble recalling what he’d just read or heard in class. At the advice of his doctors, he avoided school for an entire week, watching as the work piled up.

“My short term memory was just foggy until I recovered,” he said.

According to Kathy Lawler, director of neuropsychological resources at Penn, Donnelly’s situation is typical of most individuals who suffer head trauma.

“You’ll be fine if you don’t do anything, but the minute you go to do something like read for an hour, you get a headache,” she said. “People who have concussions will say, ‘The things that I used to take for granted — reading a chapter in a book — it takes so much effort, I’m so slow’”

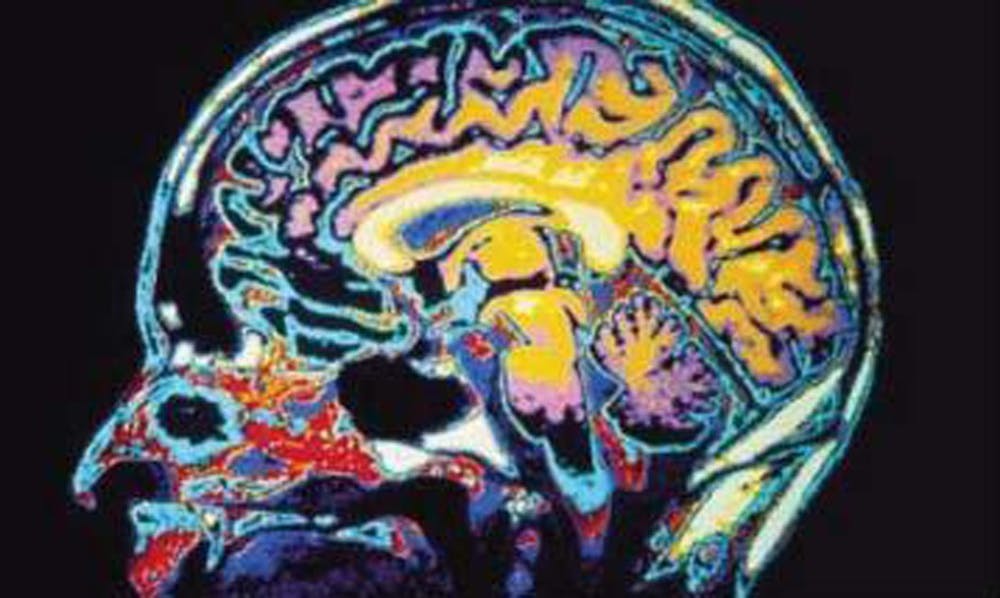

According to Lawler, functional neuro-imaging experiments show that more of the brain is used to accomplish easy tasks in the days after a concussion. Basic activities simply require more energy.

Like an ankle sprain, the best cure is rest. Mental exertion — like the daily college grind — can prolong the symptoms of a concussion.

“Sometimes I feel like what I’m doing is damage control,” said Lawler, who sees a variety of athletes come through her office every year.

Luckily for student athletes like Donnelly, the combination of Penn’s Division I football program, world-class neuroscience department and academic advisers means that support is available to help student athletes manage the lingering consequences of head trauma.

“We have a really good team approach,” Lawler said. “So I think we have very good resources.”

With a medical note from his trainer, Colin was able to postpone the one test he had during that critical week after his concussion. His housemates, also athletes, have had similar accommodations after recent bouts with head injuries.

“The professors are really understanding about it,” Donnelly said.

According to Alice Nagle, associate director of Student Disabilities Services at Penn, only one or two students come to her office each semester after suffering a concussion. Most seek out an academic adviser in their respective school instead. Colin and his housemates received help from their Wharton advisers.

“I felt that as an athlete, I was responsible in dealing with my classes to the best of my ability,” Donnelly said. He wasn’t aware of Penn’s disability resources, though the business school academic advisers were helpful for him.

“There are mechanisms in place, and I think that when we know someone has a concussion, we do a really good job medically and academically and psychologically helping them manage,” Lawler said.

But for the resources to be utilized, the doctors first have to see and diagnose patients. Before that becomes the norm, Lawler added, athletes must be educated about head injuries. She’s hopeful awareness will continue to grow.

“Penn has really developed over the past five to six years, really improved their education and recognition of concussions,” she added.

Without football, even a Wharton workload couldn’t fill Donnelly’s time once he recovered. Last spring he walked onto the track team, and he hopes to compete in the decathlon for the Quakers.

For now, he continues to spend his days at Franklin Field — just off the gridiron turf and onto the hard track.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

DonatePlease note All comments are eligible for publication in The Daily Pennsylvanian.