Think political discourse is ruder than ever? According to a recent Penn study, Congress disagrees.

The Annenberg Public Policy Center released its fifth report on civility in Congress last week. It based its research off of a congressional rule called “words taken down.”

Every time a speaker uses inappropriate words on the floor of the House of Representatives, a representative can move for the words to be “taken down.” Normal debate stops as the chair deliberates whether the words were indeed inappropriate. If so, the member is banned from speaking for the rest of the day.

When Annenberg’s report started in 1997, “they were going through and using THOMAS” — Congress’ online record database — “to find ‘taking down’ incidences and recording details about it,” explained College and Wharton junior Laura Yu, who conducted the research for the project. A quick keyword search on THOMAS could find you every instance the phrase “words taken down” was uttered in Congress’ history.

Researchers wrote down who actually said the phrase, what inappropriate words were uttered and whom the words were directed to.

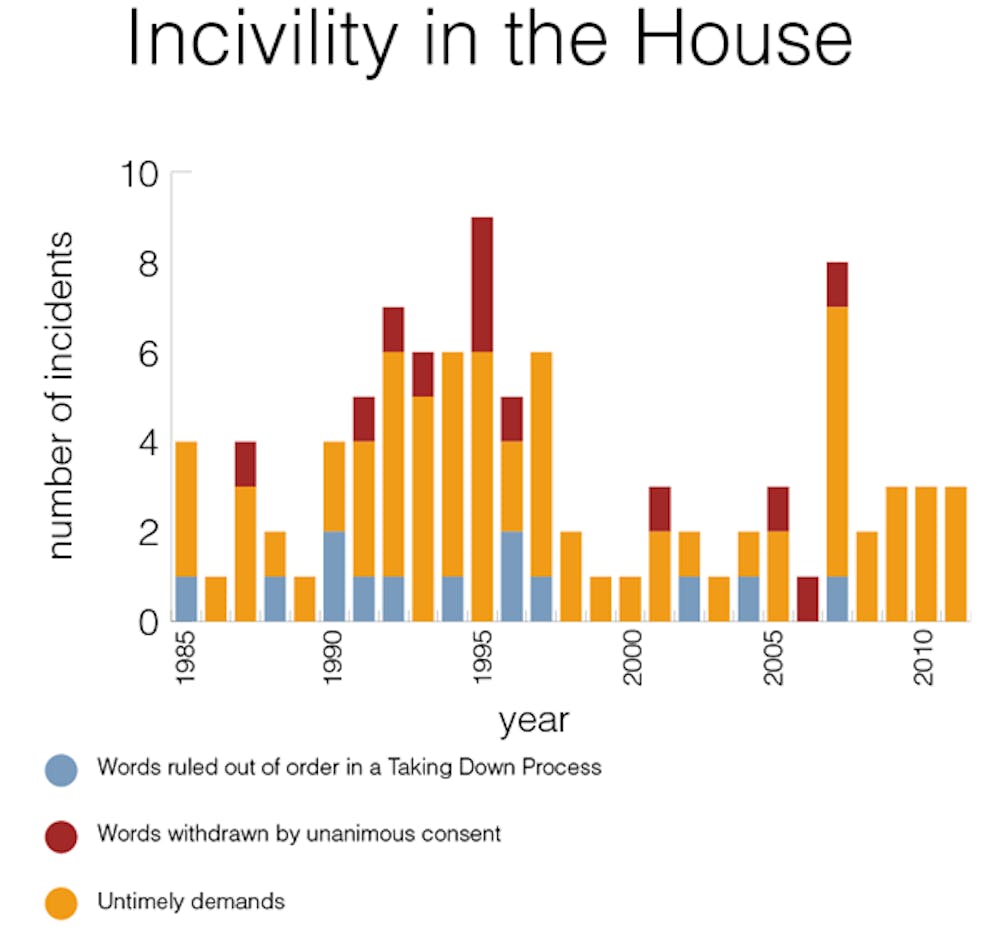

The report compares the number of times words were taken down across different congressional sessions and determines whether Congress was more or less “civil” that year.

The current 112th Congress “has not produced the sorts of incivility that disrupted the first session of the 104th,” said Communications professor Kathleen Hall Jamieson, also the director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center and author of the report.

The 104th session in 1995 was the first time Republicans held a majority in 40 years. It saw a record eight “words taken down” that year. By comparison, the current 112th session is the first Republican majority rule since 2007, but it has seen only three instances of recorded incivility. The report predicts that, since 2012 is an election year, a lot of campaign rhetoric will spill into Congressional sessions, making way for a more uncivil session later in the year.

Yu noticed that June and July are when the greatest number of words are taken down. “It’s right before the August recess,” she said, explaining that a lot of big, contentious issues — health care, for example — get pushed back in the agenda until Congress is forced to debate the issues in June and July. This inevitably leads to more contentious dialogue.

A wide variety of words have been taken down since 1935, the earliest year considered in the report. The report quotes Rep. Mo Brooks (R-Ala.) referring to “socialist members of this body” on the House floor. Another representative was ruled out of order in 1963 for making up an unwelcome nickname for Don “Pinko” Edwards. More recently, former Rep. Anthony Weiner (D-N.Y.) was asked to take his words down after he called the Republican Party “a wholly owned subsidiary of the insurance industry” in February 2010.

Some criticizers have argued that counting words taken down doesn’t accurately measure civility.

“This reasoning fails to take into account that our national political dialogue has become so coarse that ‘uncivil’ rhetoric barely causes anyone to think anymore,” wrote political expert Ilona Nickels in a letter to the editor to The Washington Post. In addition, Nickels argued that “as citizens of a society more accepting of crudeness, members of Congress have developed thicker skins. Rather than object to insults, they are more likely to return them in kind.”

Despite those criticisms, Jamieson leans on the quantitative nature of the words-taken-down criteria. “The taking down process is the only reliable cross-time measure of discourse that the House itself has ruled out of order. Our report is not about incivility in general in the House, but incivility captured by this measure,” Jamieson responded.

Yu, who is currently studying in Washington with the Washington Semester Program, agrees with Jamieson. “If there’s a better [way to measure incivility], no one’s found it yet. A lot of people will tell you that Congress is a lot more uncivil than before, but this is the only research that I’ve seen … that looks at it quantitatively.”

And the report shows promising statistics. “People always say [the incivility] is so terrible now, but there’s been periods throughout history where I think it’s been just as terrible,” Yu said.