On the morning of Sunday, July 23, seven people were shot and two were stabbed in the span of four hours in Philadelphia, including a 22-year old man who was shot in the face.

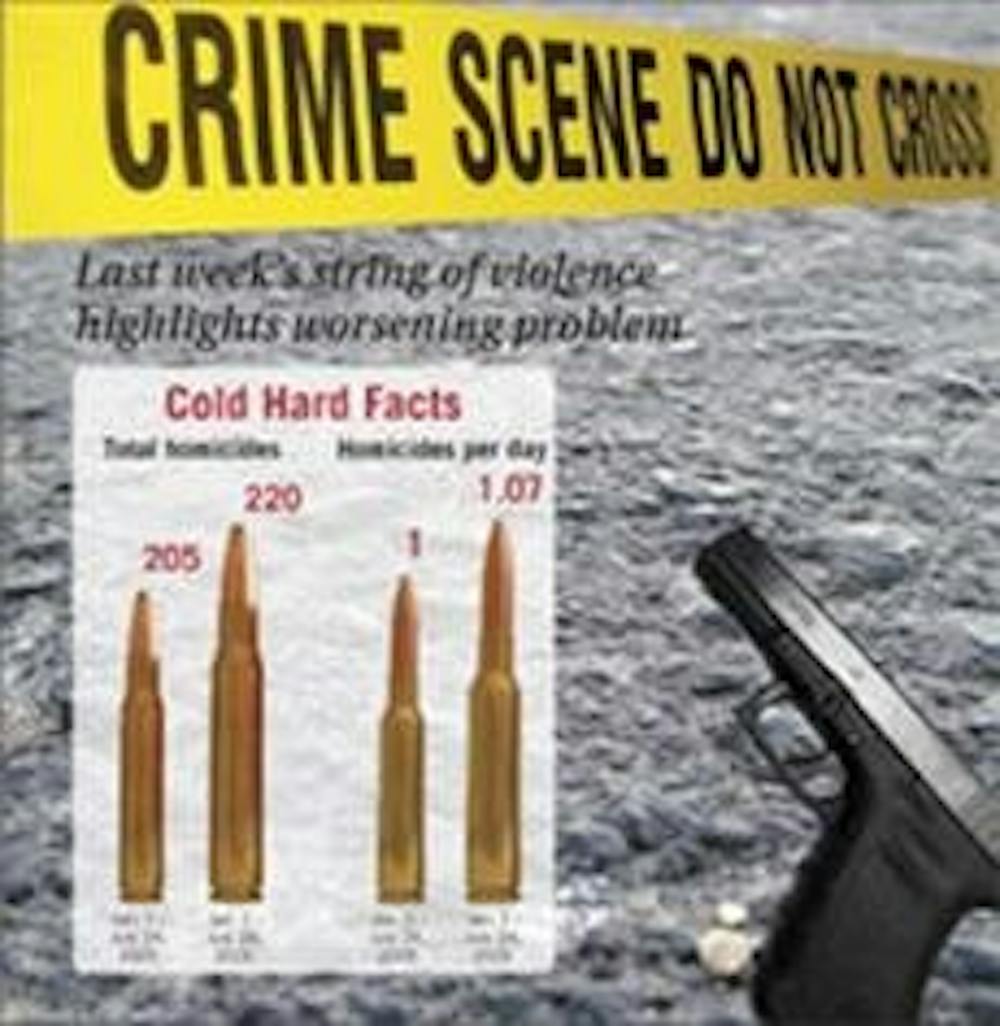

This spate of violence is only a small part of the city's gradual increase in crime, but it helps illustrate Philadelphia's newest grim statistic: the city's homicide rate has increased by 7% from this point last year.

As of Monday, July 24, Philadelphia registered 220 homicides, compared to 205 at the same point last year.

While cities such as Los Angeles and New York City have each reported double-digit reductions in murder rates, the increase in violence in Philadelphia has become the status quo. Between 2004 and 2005, Philadelphia experienced an increase of 12% in its numbers of homicides.

The cause behind this increase in crime is hotly debated, but the demographics behind Philadelphia's violence provide a glimpse into the problem.

The three most likely areas for a homicide to occur are the northern, western, and lower northeastern parts of the city, areas of Philadelphia that are afflicted by concentrated poverty.

According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, 80 percent of the homicide victims have been African-American and 89 percent have been male.

Handguns were the weapon of choice 82 percent of the time, and young adults, ages 18-24, make up the most numerous age group that are victims of gun violence.

"For Philadelphia, there's a large portion of its community living under extreme isolation," said Dr. Lawrence Sherman, director of Penn's Jerry Lee Center of Criminology. "Greater alienation of young black men in poverty areas are accounting for most of the increase in homicide."

Although the statistics may be telling of the typical victim of violent crime, they are not exclusive to young black males.

Examples abound of members of the community that become the unlikely victims of gun violence, such as Neshia Wright, a 27-year old mother of two who was struck by a stray bullet in the chest and died half an hour later.

Wright's case shows that gun violence has escalated into community-wide problems with numerous different causes and no obvious solution.

One of the explanations for the increase in crime is the economic depression that has hit inner-city neighborhoods since manufacturing jobs have left the city and a low-wage service economy has replaced it.

"The inner-city rests on three strategies for acquiring capital: low-wage jobs, welfare payments, and the irregular underground economy," said Dr. Elijah Anderson, a sociology professor and the author of the book Code of the Street. "Since the inner city has transitioned away from manufacturing, then residents must cope by using another strategy."

Others problems are social in nature, such as unemployed heads of households and an elevated high school drop out rate.

The availability of guns and the easy access to the drug trade also have become factors in the steady rise of crime in the city.

"A young person can get his hands on a gun before he can get a textbook," said Dorothy Johnson-Speight, founder and executive director of Philadelphia anti-violence group Mothers in Charge. "And we live in a culture that says that it's OK to have a gun; it's a message that's promoting a culture of violence."

In order to combat the violence, Pennsylvania governor Rendell pledge 170 state police officers to patrol Philadelphia highways, freeing up Philadelphia cops to hit the streets.

However, many inner-city residents do not trust the efforts of the Philadelphia Police Department, according to Anderson.

"When cops don't always come to emergency calls or when people see a criminal back on the street two weeks later, it undermines faith in the law or its agents," said Anderson. "There is a limited amount of faith in civil law, so street justice fills the void and street credibility becomes ever more important."

Despite the myriad number of causes, the number of solutions aren't as clear-cut.

"The best solution [for violence deterrence] is police searching people carrying concealed weapons in public," said Sherman. "It discourages people from carrying guns, giving them less opportunity to shoot, and homicide goes down."

Regardless of the solution, Johnson-Speight provides some insight into the shared commitment of Philadelphia and its residents.

"Whether it's working with a young person at risk with educational counciling, anyone can make a difference," she said. "The key is that everybody needs to do something."