The website babe.net published a story two weeks ago on sexual assault allegations that detailed a date and subsequent sexual encounter between a woman (who went by the pseudonym Grace for the purposes of the story) and the comedian Aziz Ansari.

It’s a detailed account of how the two met at a 2017 Emmy Awards after-party, traded numbers, and eventually went out in New York City. They had dinner at a restaurant and later returned to Ansari’s apartment, where Grace alleges that Ansari aggressively tried to hook up with her, even after she asked him to “chill.” When he persisted, Grace told him, “I don’t want to feel forced because then I’ll hate you, and I’d rather not hate you.”

Ansari didn’t take the hint and the encounter continued.

Most of the response to Grace’s account has centered on whether or not her interaction with Ansari was truly sexual assault or just an awkward date and bad sex. There were scores of opinion pieces published, and impassioned Twitter threads from both sides. Comedian and political pundit Bill Maher declared that #MeToo was now McCarthyism.

Watching the internet erupt, I felt an overwhelming sense of sadness. Grace’s story was a heartbreaking read, not just because I was a huge fan of Aziz Ansari, but because it was achingly familiar.

Throughout my high school and college years, I’ve listened helplessly as friends and acquaintances have described encounters with their own Azizs, and I’ve cried to them when I had my own. It’s an ugly tapestry of close-calls and unwanted sexual encounters.

Litigating whether Grace’s encounter fell under the vague definition of sexual assault felt like it was missing the point. Grace’s own identification of the encounter as sexual assault comes at the end of the piece, after she talked it over with friends because she “wanted validation that it was actually bad.”

It became clear to me that there is no consensus of what the term sexual assault means, and its usage becomes an easy way to stop or deliberately confuse conversation about how we as a society approach sex, and how our attitudes about sexual relations are broken.

The meat of Grace’s story — an uncomfortable sexual encounter that left her feeling confused and taken advantage of, where she felt like her boundaries were crossed and her voice was silenced — was lost in an argument about semantics, where everyone had a hand in defining and explaining what happened to Grace except her.

We’re obsessed with defining women’s sexual experiences for them. We want clear definitions because they make for easy solutions. If we let nuance into our conversations surrounding sexual assault and rape culture, then we’re suddenly faced with the reality that our most basic societal script for sexual encounters is based on antiquated ideas of female virtue and toxic masculinity.

According to the 2015 Association of American Universities Campus Climate Survey, by senior year, nearly a third of Penn’s female undergraduate population will experience sexual assault. In the survey, which spanned 27 institutions, the most common reason women cited for not reporting their sexual assaults was that they did not believe the incident was serious enough.

Now, just weeks ago, a new public survey has highlighted sexual harassment committed by Penn faculty and victims’ frequent frustrations with the administration's response. To the majority of people in the Penn community, none of this will come as a surprise

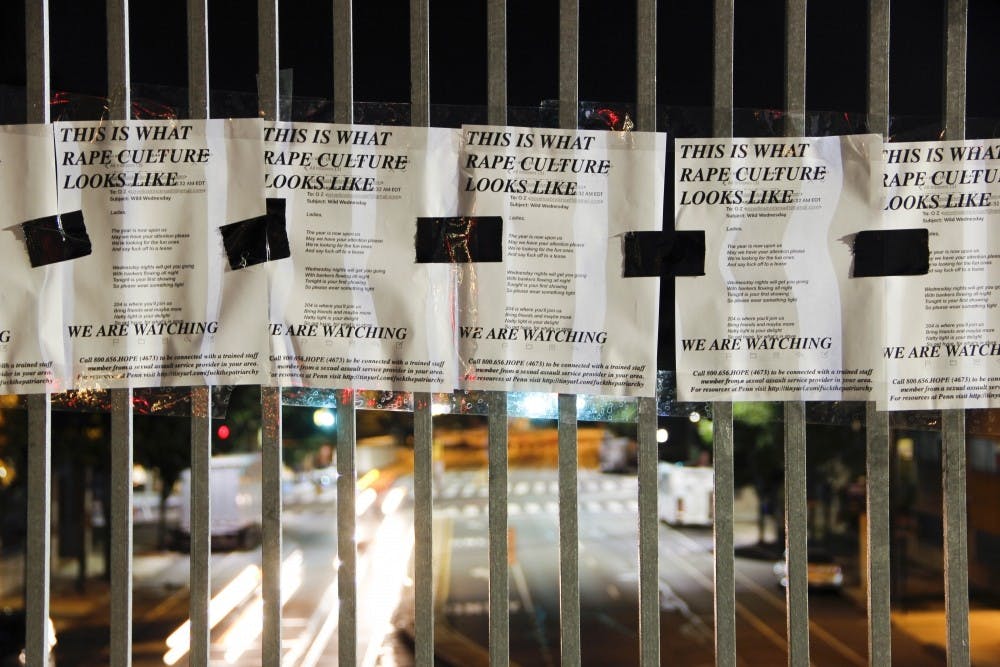

In 2016, members of the off-campus fraternity, OZ, infamously sent a sexually suggestive email to Penn freshmen. When faced with this scandal, Penn’s administration made a show of concern and appointed a task force whose eventual recommendations were that parties and alcohol were to blame. Instead of listening to survivors (or even Penn’s student community at large), the task force instituted a series of rules that only served to give more social power to fraternities and incentivize a move toward more off-campus socializing, putting potential victims out of reach of the Penn Police Department and its sexual assault resources.

The national events of the past few weeks have left me more hopeful that we can change some of the fundamental issues that lie at the heart of rape culture and campus sexual assault. But none of that will happen if we don’t listen to women, and really listen, when they are highlighting experiences where they felt uncomfortable or violated. Here at Penn, we still have a lot of work to do.

REBECCA ALIFIMOFF is a College sophomore from Fort Wayne, Ind. studying history. Her email address is ralif@sas.upenn.edu. Her column usually appears every other Wednesday.