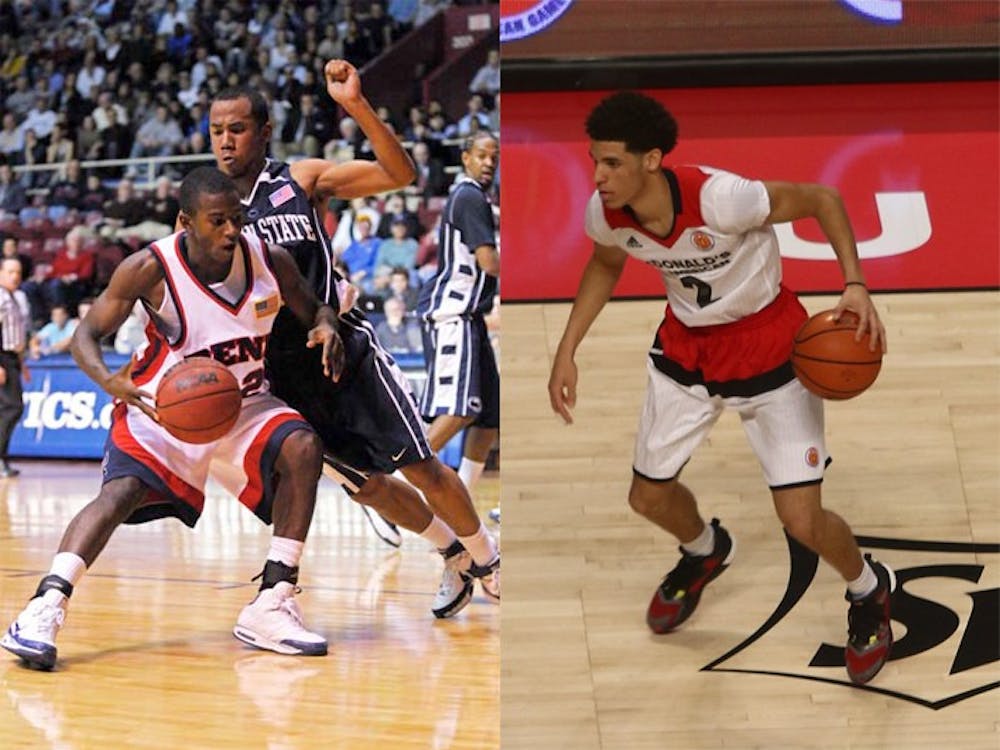

Years before Lonzo Ball began making a name for himself, Harrison Gaines led the Ivy League in assist to turnover ratio as a freshman. File Photo | The Daily Pennsylvanian; TonyTheTiger / CC 4.0

If you follow basketball at all, then it’s probably safe to assume that you’ve heard of Los Angeles Lakers guard Lonzo Ball and his outspoken father, LaVar Ball. After all, it’s pretty hard to not hear about them when they are doing stuff like this and this.

A better question, though, is have you heard of Lonzo’s agent and former Penn basketball player, Harrison Gaines?

It’s perfectly understandable if you haven’t. Gaines has not played for the Quakers since 2009 and until the world saw Lonzo shake hands with Gaines right after being drafted on June 22, very few probably even realized that Lonzo’s agent wasn’t his dad. That’s pretty remarkable for someone who is so closely connected to one of the world’s most famous athletic families — a family that will soon have its own reality television series.

In the days following the NBA Draft, a Sports Illustrated profile helped unshed some of the mystery of Gaines. It describes how the 28-year-old Gaines, despite not having a single client playing in the NBA, was able to win over the Ball family. And while the article does discuss Gaines’ decisions to come to Penn and ultimately to transfer to UC Riverside after just two years with the Red and Blue, much still remained unclear about his time in University City.

Unclear it shall remain no more.

. . .

Even as a freshman, Gaines showed the makings of a future sports agent.

“I’ll tell you what he would do,” former Penn guard and Gaines’ freshman year roommate Tyler Bernardini recalls. “In the dorm rooms, I would buy my sodas, and he would take them, but he would always leave a dollar.”

For Bernardini, that kind of behavior was unusual. He was used to friends taking his sodas, but the idea of actually being paid back for the sodas was completely foreign.

In hindsight, though, Bernardini’s memories of Gaines don’t seem all that surprising. Isn’t that the exact kind of financial responsibility you would hope and expect to see from someone who now has a fiduciary duty to a player worth tens of millions of dollars? Probably, but for Bernardini, the story says something even simpler than that.

“That just shows you the kind of guy he was,” Bernardini says. “He’s a guy that just is genuine, and even if he took it, he’d never do something without making sure it was just a dude trying to go about it in the right way.”

On the court too, Gaines quickly proved himself as one of the team’s hardest workers.

“He was the one guy who was always in the gym working out, playing and trying to get better every single day, and I think that kind of rubbed off on a lot of us on the team,” former Penn guard Remy Cofield, another teammate and close friend of Gaines, remembers.

And that shouldn’t be taken as hyperbole. For Gaines, there truly was no such thing as a day off. Even on weekend nights, while the rest of campus was enjoying the latter half of Penn’s “work hard, play hard” culture, Gaines could be found getting shots up in the gym.

“I remember like walking past the Quad or walking past all the frats on like a Friday night, and we’d be in like the Palestra or Weightman Hall — we really liked that just for some reason — so a lot of nights we’d spend up there just the two of us, just working out or playing one-on-one,” says Bernardini.

All the hard work paid off for Gaines once the 2007-2008 season finally rolled around. Despite his youth, the rookie quickly proved himself to then-coach Glen Miller. That year, the team finished with a mediocre Ivy League record of 8-6, but it also seemed to have found its point guard of the future in Gaines. As a freshman, Gaines led the entire conference in assist-to-turnover ratio.

Gaines was excited for the team to continue progressing the next season, but the Quakers took a step backwards, struggling mightily as the team finished second-to-last in Ivy standings. Worse yet, Gaines suddenly felt as if his role on the team was in jeopardy. He managed to increase his scoring average to 9.9 points per game, but the message from coach Miller was clear. New freshman Zack Rosen was the point guard of the future, and Gaines’ job was to complement Rosen off the ball. That didn’t sit well with Gaines, so he decided to transfer.

In his March 2009 announcement that he would be transferring from Penn, Gaines explained how he was hoping to find a school that would provide better “long-term satisfaction.” More specifically, he stated, “I need to attend a school where I have confidence in the basketball team’s leaders.”

Less than a year later, Penn fired Miller after an 0-7 start to the season.

The school Gaines ended up deciding on was UC Riverside, which was much closer to his family’s home in Victorville, California — just an hour’s drive away. From a basketball perspective, though, things did not get much better for Gaines. After sitting out a year due to NCAA transfer rules, he struggled to carve out minutes in his final two years of eligibility. He finished his career at Riverside with averages of just over three points and one assist per game.

Still, Gaines has no second thoughts about his decision to leave Penn.

“You know what, I don’t regret the transfer to the Riverside,” Gaines says. “When I look back to it, now I’m 28, when I look back on decisions from back then, each stop shaped and helped to get me where I am today. If I stayed at Penn for four years and graduated from there, do I end up at 28 is in the position I’m in? Maybe, maybe not.”

At the same time, Gaines harbors no ill will towards Penn. He still values the time he spent at Penn in more ways than one.

As a player, Gaines remembers the battles his team fought in the Palestra fondly. Some of his favorite games came against Cornell, which won the Ivy League in both of Gaines’ seasons at Penn. And just for those keeping score at home, Cornell’s coach at the time was none other than current Penn coach Steve Donahue.

Off the court, Gaines continues to utilize many of the connections he made during his time in University City, like Cofield, who now works in the front office of the Boston Celtics.

“He represents a client [Lonzo Ball] right now for the Lakers,” Cofield says. “You know, I would talk to him in the spring and everything, trying to get his client to come and work out for us, so yeah, it’s been good.”

Since the Celtics held the No. 1 draft pick until trading down two picks to the Philadelphia 76ers’ — who happen to be owned by another Penn alum in Josh Harris — the relationship between Gaines and Cofield had the potential to change the entire future of the NBA.

Ultimately, of course, Lonzo was drafted second overall by the Lakers, but that has done little to discourage Cofield from wanting to work with Gaines again in the future.

“He’s definitely going to have more clients, and I’m definitely going to have more conversations with him about those guys as well,” Cofield adds.

On top of all Penn did to expand Gaines’ professional network, he still stays in touch with several former classmates and teammates as friends, like Cofield and Bernardini. Not to mention, his wife is also a Penn alum.

So while the question of what could have been for Gaines if he stayed at Penn will always be there, he’s found peace with his relationship to the university, which at least on the surface, seems pretty complex.

In Gaines’ own words: “I loved Penn. Always have, always will.”

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate