Black History Month, observed during the month of February in the United States, is held annually to honor the accomplishments of black Americans in society.

Penn Athletics has had many influential black people walk through its gates. Let's travel back in time to recognize these members of our community who impacted not only Penn, but also the global community.

Eddie Bell, alongside teammate Bob Evans, was one of the first two black football players for the Red and Blue. Although touted as highly skilled on offense, Bell was named a two-time All-American and All-East player in 1951 and 1952 for his defensive abilities. Coach George Munger kept him almost solely on defense, and Bell went on to represent Penn in the 1953 College All-Star game. A multi-sport athlete, Bell was a sprinter on the track team in the spring and helped the Quakers win the Sprint Medley Championship of America at the 1951 Penn Relays.

After his graduation in 1952, Bell was a cornerback for the Philadelphia Eagles and a linebacker for the Hamilton Tiger Cats and New York Jets.

Franklin Field, where Bell played during his time at Penn, was host to one of the most significant moments in college football history. The game between Penn and Brown on Oct. 6, 1973 was the first ever matchup between two starting black quarterbacks. Martin Vaughn, a two-time record setting All-Ivy quarterback, led the Quakers to a 28-20 victory over the Bears, who were led by Dennis Coleman. Vaughn, the first black quarterback to start for Penn, threw for 200 yards and held numerous other program records for touchdown passes, passing yards, and total offense. The team captain in 1974, Vaughn was ranked fifth nationally in total offense in his final season for the Red and Blue.

Incidentally, sophomore Ryan Glover, the starting quarterback for the Quakers in the 2018 season, is the only starting black quarterback in the Ivy League.

Sophomore quarterback Ryan Glover

Comparatively, four black starting quarterbacks played in the conference between 1969 and 1974.

"Kids don’t get the same opportunities to play that position while growing up or maybe aren’t recruited because of subconscious biases regarding the importance of the position,” Glover said. “I think Penn is a really safe space and is full of diversity; we all play football as one big brotherhood. I found out that I was the only black quarterback at the end of last season and was surprised. At the end of the day, we are still playing football, so that statistic doesn’t factor into my play.”

The historic Palestra has also seen its fair share of heroes play in its hallowed halls.

David “Corky” Calhoun, a 1972 Wharton graduate, is regarded as one of the greatest all-around players in Big 5 history and played three seasons with the Quakers before being drafted in the first round of the 1972 NBA draft by the Phoenix Suns.

In his time at Penn, Calhoun scored 1,066 points, was named All-Big 5 and All-Ivy three years in a row, and won Big 5 MVP honors his senior year. The Quakers won the Ivy League title and made the NCAA Tournament each year he played and reached the East Regional Final in 1971 and 1972, finishing the season ranked second in The Associated Press' final 1972 poll.

Calhoun joined the Portland Trail Blazers as a free agent in 1976 and was a member of their 1977 NBA championship team. He ended his eight year NBA career, the longest of any Penn athlete, with the Indiana Pacers after choosing to work in marketing over a professional career in France.

John Edgar Wideman graduated from Penn in 1963 with Big 5 and All-Ivy accolades and led the Quakers to a 20-8 Ivy record and a Big 5 title. A Big 5 Hall of Famer and a two-time team captain, he also excelled immensely off the court.

Wideman was the second black person to become a Rhodes Scholar. A member of Phi Beta Kappa, he was also a Ben Franklin Scholar and was awarded the Thouron Award, a scholarship for a graduate exchange program between Penn and schools in the United Kingdom.

In 1967, he returned from Oxford to teach English at Penn, and in 1972, he left to pursue his writing career. He wasn’t one to shy away from social commentary in his work. "Philadelphia Fire" (1990), set in West Philly, is based on the troubled social and political environment that arose as a result of the bombing of the Afrocentric MOVE House in 1985, while "Two Cities" (1998) discusses the urban black community.

The only person to win the Faulkner Award twice, for "Sent For You" (1984) and "Philadelphia Fire", Wideman garnered a National Book Critics nominationfor his work "Brothers and Keepers," a nonfiction book about his brother’s conviction for murder.

Tony Price led the Red and Blue to an Ivy title, a Big 5 Championship, an East Regional Championship, and a Final Four appearance in 1979. The Ivy League and Big 5 Player of the Year during Penn’s greatest ever basketball season, Price played a huge role in pulling the Quakers through the tournament, scoring double digits in each game. He scored 27 points against Iona, 25 against North Carolina, 18 against Michigan State, and ended his career with 31 points against DePaul in the third-place game.

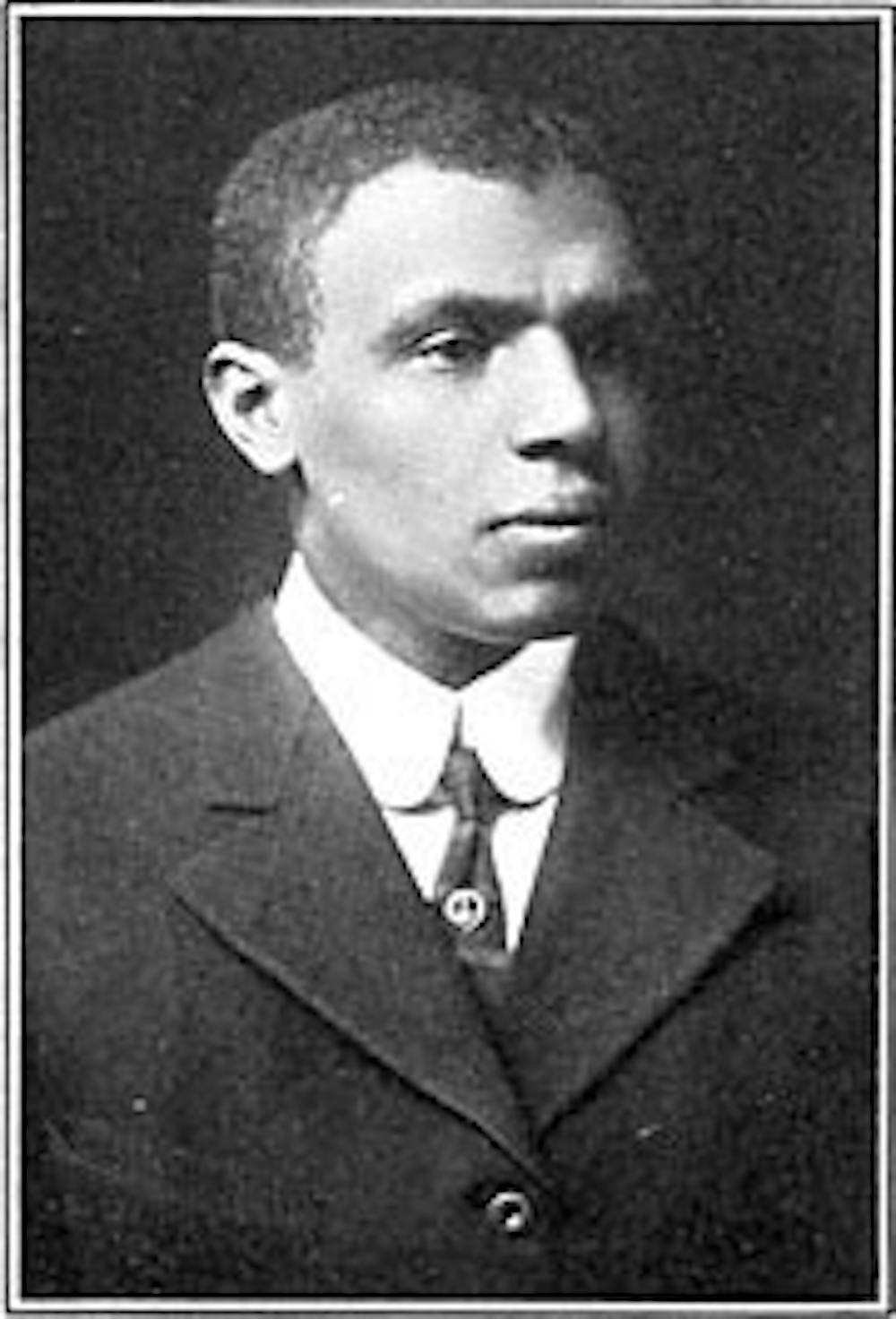

John Taylor Baxter (Track and Field) | Photo from University Archives and Record Center

During his career, Price won two Ivy League Championships and was a two-time All-Ivy selection. Voted into the Big 5 Hall of Fame in 1985, he was drafted as the seventh pick in the second round of the 1979 NBA draft by the Detroit Pistons. Waived by the Pistons, he ended up playing for the San Diego Clippers for the 1980-81 season before going on to work in the insurance industry for over 30 years.

John Baxter Taylor, born to former slaves in Washington D.C., was the first black person to win an Olympic gold medal.

He won the men’s 1600-meter relay alongside fellow Quakers William Hamilton and Nate Cartmell and advanced to the finals of the men’s 400 at the 1908 Olympics in London. A graduate of the School of Veterinary Medicine's Class of 1908, Taylor was a member of the track team from 1903-1905 and 1907-1908. With a stride of 8 feet, 6 inches, he set the world interscholastic record for the 440-yard dash, running it in 48.6 seconds. Tragically, Taylor succumbed to typhoid fever on Dec. 2, 1908 at the age of 26. Thousands of Penn students, alumni, and teammates attended his funeral.

Soon after Baxter came Willis Nelson Cummings, a Texas native, who was the first black captain of a varsity team at Penn and in the Ivy League. The track star was the junior and senior champion of the 1918 Middle Atlantic AAU Championships, the first to win both championships in the same year. One of two black people in the School of Dental Medicine's Class of 1919, he was the first black person to be admitted into Omicron Kappa Upsilon, the national dental honor society.

Cummings was at the receiving end of discrimination on multiple fronts. Some schools refused to let their athletes run against him, and the 1918 cross country team did not take a team photo as the administration did not want to show a black man as the captain. After his graduation, the records of most of his accomplishments at Penn disappeared. Cummings himself brought in his own scrapbook as evidence of his accomplishments, after which his name was restored in the official records. He went on to open the Dental Society of New York in Harlem to admit black and Jewish people as members.

Historically harmful practices have also manifested themselves in some modern institutions more covertly. Senior KJ Smith, a member of the men’s golf team, described some of the discriminatory practices that surround the sport.

“The Penn community has been extremely welcoming to me, but because of the nature of the game of golf, you can feel tensions of the past," he said. "I grew up in Atlanta, where you see black doctors, congressmen, and businessmen, and in the public sphere, you see a lot of black golfers. I didn’t bat an eye because I was not alone, because the course I grew up in and played at was predominantly black.”

“There is a huge difference between the public courses and private courses, in which you needed to have a membership,” Smith added. “I would need to get haircuts, as my natural hairstyle wouldn’t be acceptable. The way I dressed at public courses was very different than how one had to dress at private courses."

The legacy that these distinguished athletes have left on Penn Athletics will last for years to come, but there's still work to do to give them the recognition they deserve.

This is Part I of a two-part series on the history of black athletes at Penn. Part II will focus on notable female athletes.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate

Most Read

More Like This