Less than three weeks after teaching assistant Stephanie McKellop sparked national controversy for tweeting about using progressive stacking in the classroom, Penn Debate Society went head-to-head against the Penn Philomathean Society to debate whether the teaching method does more harm than good.

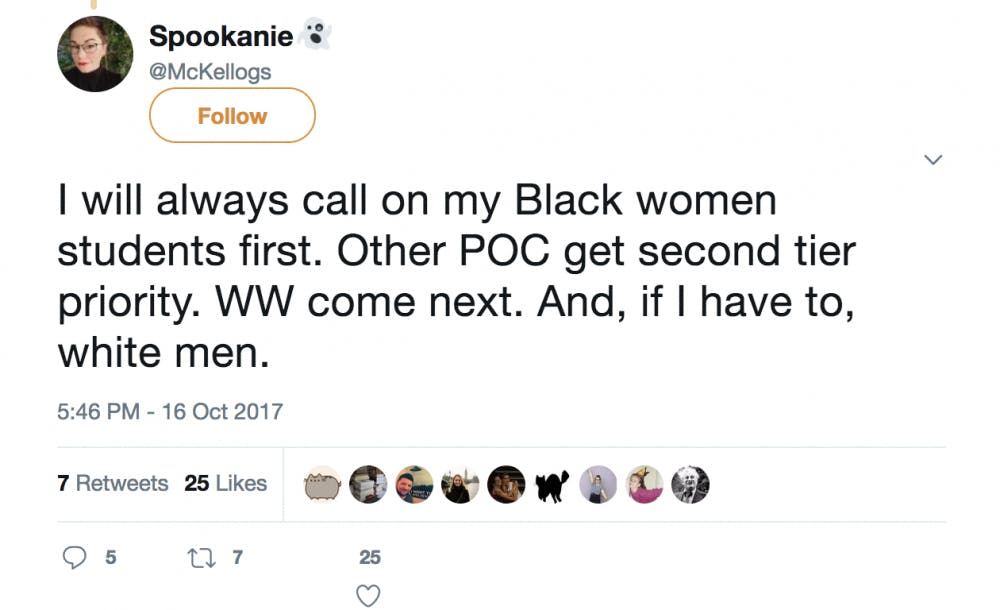

Progressive stacking refers to a teaching method that involves giving historically marginalized students priority in the classroom. In a tweet dated Oct. 16, McKellop wrote, "I will always call on my Black women students first. Other POC [People of Color] get second tier priority. WW [white women] come next. And, if I have to, white men."

In a parliamentary-style debate moderated by the Penn Political Union on Oct. 9, students argued whether it is appropriate for McKellop to use progressive stacking in her class. McKellop is a TA for the class History 345, “Sinners, Sex and Slaves: Race and Sex in Early America.”

PDS President and College junior Alex Johnson said the debate was intended to address the effectiveness of the method, not its intention.

“The debate is more about whether progressive stacking is actually an effective method of making sure people feel comfortable and feel prioritized in academic spaces, not whether if that comfort and that safety is a good thing at all,” Johnson said. “Both sides agree that it is a good thing.”

Two PDS members, including Johnson, argued against progressive stacking, while two Philomathean Society members argued in support of progressive stacking. The students were not assigned according to their personal views.

The PDS team argued each student’s privilege in a classroom cannot be immediately quantified based on their identity. False “oppression olympics” can lead to an arbitrary yet highly stratified system “that turns privilege into a system of points,” Johnson said. Minority students may feel they are heard only because of this system and not because of their individual merit.

“The opposition never gave us any reason as to why we should prioritize, for example, gender over race in terms of oppression, or why we should prioritize the experiences of a Latina woman over an Asian man,” PDS member and Wharton sophomore Stephanie Wu said.

The opposition argued that “academia is not a vacuum,” and that it is impossible to understand the modern effects of slavery and gender discrimination without stressing the lived experiences of minority students.

“You could be the most well-read student in the classroom, but you would not have the same understanding as someone who has experienced the modern manifestations of these institutions,” Philomathean Society member and Wharton and Engineering junior Prakash Mishra said.

The PDS team argued progressive stacking could make white male students feel excluded and prevent them from taking future classes on gender and race. The opposition responded that progressive stacking can increase empathy by placing white male students in a disadvantaged situation.

“It forces them to see that same discourse from a light of lower privilege, which is the only way you can get someone to understand what it means to not have privilege,” Mishra said.

The groups also debated whether asking minorities to speak first strengthens their voices in the classroom. The PDS team argued this could prevent minority students from correcting misinterpretations of those who would otherwise speak before them.

“If you have the last say, you get to define the conclusion that the discussion has come to and what the main takeaways are,” Wu said. “That can be extraordinarily powerful.”

The opposition rebutted that students who speak first often dominate the rest of the conversation. Asking minority students to speak last could lead to unwanted pressure and “put minorities on the defensive,” Mishra said.

During a question and answer session, students asked if progressive stacking was appropriate in specific cases, such as classes where white, male students are outnumbered or a class with a socially-anxious white student. Wharton sophomore Toni Oloko said he was interested in the balance between representing minorities’ voices and avoiding “oppression olympics.”

“There are people who support diversity and liberal values but at the same time don’t support the TA’s policy,” PDS member and College freshman Anish Welde said. “I think even though diversity and accepting many different perspectives can be an end goal in society, we have to realize that there are many ways of achieving this.”

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

Donate