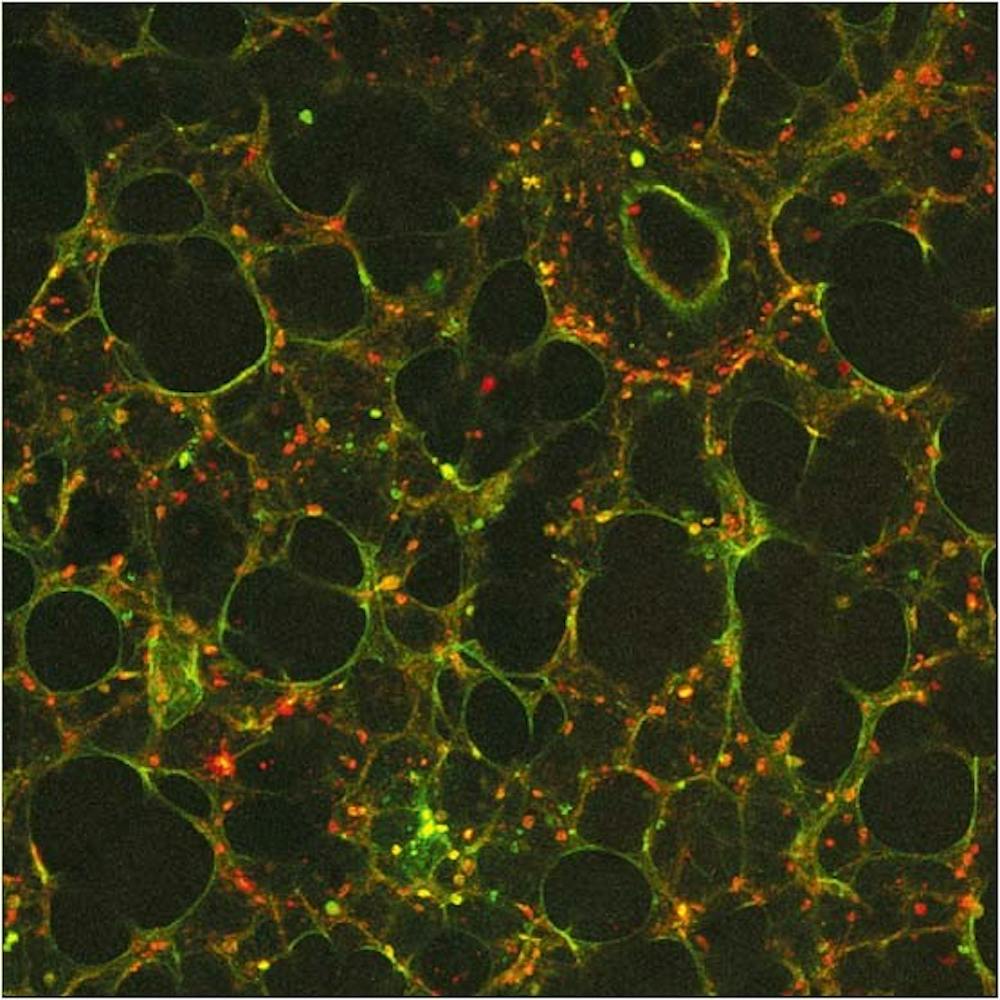

Confocal microscopy image of a region on an unstretched lung slice — Jessie Huang has discovered a new method of research that allows researchers to use lung slices as opposed to whole animals or cell cultures.

How far can your lungs stretch?

This is a real concern for intensive care patients on medical ventilators, machines which help patients breathe. However, in the course of keeping patients alive, ventilators can overstretch and injure the lungs, sometimes killing the patient.

Engineering senior Jessie Huang has created a new scientific method that will help scientists who are researching this phenomenon.

Huang recently won the 2013 Undergraduate Student Paper Award from the Philadelphia Engineering Foundation and the Engineers’ Club of Philadelphia for her paper titled “Rat Precision-Cut Lung Slices as a Model for Deformation-Induced Lung Injury Studies.” The paper details a new method for research about ventilator-induced lung injury or VILI.

Most researchers who study VILI look at either cells or whole rats with intact lungs. However, the cell model is not a good representation of the biological environment of the lungs, according to Huang.

Using a whole rat for each test solves this problem but introduces others. For instance, Huang says it’s a wasteful process.

Huang’s paper details how to use slices of lungs from rats as opposed to whole lungs from animals for VILI research.

“From one animal, you can get a lot of slices,” Huang said. “You have a lot more data points, and I think it’s a more efficient use of the animal.”

Bioengineering professor Susan Margulies, who is the principal investigator in the Injury Biomechanics lab, which studies how medical ventilators injure patients’ lungs, said “Jessie built a bridge. She used the slices of real lung, which has all the complexity of the many different tissue types and cell types but created a preparation … which allowed us to have more precise control over the physical environment.”

Huang first became interested in pulmonary health as a high school student in Ontario. She was part of Smoke-Free Ontario’s For Youth By Youth program and designed anti-smoking campaigns targeted at youth about the dangers of smoking.

During presentations, Huang recalled using pig lungs to show the effect of smoking on the lungs. Using a bicycle pump, Huang and the other presenters inflated a healthy pig lung and a pig lung coated in tar to mimic the effect of smoking. The tar-coated lung could not expand as much as the healthy one.

During her first year at Penn, Huang started working in the Injury Biomechanics lab. Like most freshman lab assistants, Huang initially did odd jobs like washing glassware, analyzing data, preparing custom cell cultures and caring for animals.

“Everyone starts out the same way … you wash dishes, and you wash glassware. You take care of the more mundane tasks,” she said. “I think it’s a good experience because if you want to become someone like Dr. Margulies … you need to know how a lab runs.”

Margulies said it was during this time that Huang’s love of research developed.

After a year in the lab, Huang started this project.

“It didn’t go smoothly at first … but she really enjoyed the problem solving,” Margulies said of the research.

In fact, it took several months just to figure out how to attach lung slices to the apparatus that would be used to stretch them.

To test the elasticity of the lung slices, Huang used an indenter, a machine that pushes on the slice at a specified frequency. She needed to adhere the slice to a membrane, which would hold it in place on the machine.

There was no simple answer to this question. After trying other methods, she decided to sew the lung slice to the membrane using surgical string called suture. However, she still needed to test patterns of stitching to find one that would not affect how the slice stretched.

Eventually, she settled on a pattern that looked like a ten-pointed star and was able to go forward with her research.

“It was a lot of needle work, and I’d never sewed before,” Huang said.

Haung had the support of Margulies and all who worked in the lab, but the paper was an independent effort. “You have to work by yourself a lot of the time — you have to be in charge, set the times when you are going to come in and have the motivation to get things done ,” Huang said.

After graduation, Huang plans get a doctoral degree in toxicology and environmental health science in a pharmacology or public health program. She would like to become a researcher.

“You can never have answers to everything,” she said. “There are always more problems and ways to help people.”

A previous version of this article stated that Huang worked in the Injury Biometrics Lab. She works in the Injury Biomechanics Lab.

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

DonatePlease note All comments are eligible for publication in The Daily Pennsylvanian.