College applicants poring over acceptance rates and comparing their SAT scores to schools’ averages may have been looking at incorrect data for more than a decade.

Emory University announced the results of a three month investigation Aug. 17, which identified that the school had misreported data on admitted classes for at least 11 years.

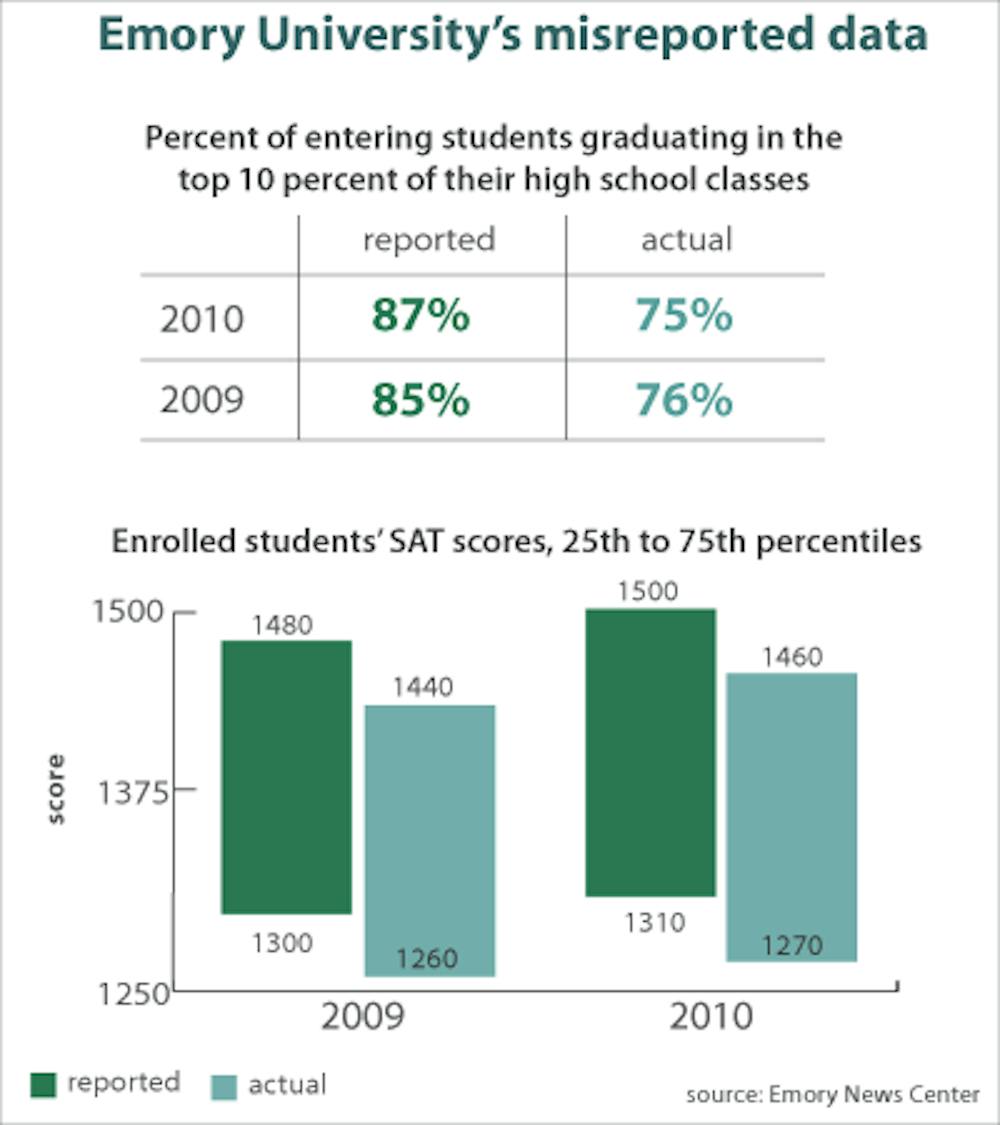

Emory inflated its admitted classes’ SAT and ACT scores by reporting admitted students’ scores as enrolled students’ scores. The school also reported inflated percentages of enrolled students who graduated in the top 10 percent of their high school classes.

“As an institution that challenges itself, in the words of our vision statement, to be ‘ethically engaged,’ Emory has not been well served by representatives of the university in this history of misreporting,” Emory President James Wagner said in a statement. “I am deeply disappointed.”

The news comes in light of Claremont McKenna College’s acknowledgement earlier this year that the school had been overstating data on its enrolled students’ class rank and SAT scores, as well as the percentage of applicants who were admitted to the school.

“You have to do everything you can to make sure that you’re shining the best light on your institution — for the real data,” Penn’s Dean of Admissions Eric Furda said. “What you can’t do is try to change data to make your class look better.”

The misreported data from both Emory and Claremont McKenna was included in various data sets and publications, and was misrepresented in rankings of colleges and universities. Some have argued that the news of purposely inflated admissions data raises questions about the role of rankings in college admissions.

“It’s a big question that has to do with why people are obsessed with the data,” President of Hernandez College Consulting Michele Hernandez said. “I’m sure more people have manipulated data — this is just the one we’ve caught.”

Hernandez also stressed that while the two schools reported incorrect data, schools are able to report misleading data as ostensibly accurate. For example, she said, Harvard University’s acceptance rate of under 6 percent is artificially lowered by a high number of students accepted from the waitlist but not included in the initial admission rate.

Furda gave an example about a school’s percentage of international students, explaining that different schools may define “international” in vastly different ways. He and Hernandez agreed that ranking systems should standardize these — and other — measures of a school that may be open to interpretation.

“Wherever there can be, without it becoming administratively unmanageable, be very clear about what you’re asking for so there can be consistency,” Furda said.

Emory has since revised its data and reported it correctly, in time for the upcoming release of U.S. News and World Report’s annual college rankings on Wednesday. But with the public’s reliance on various rankings of schools, some argue that incentives to manipulate data will remain.

“Unfortunately, higher education has become a business,” said Maria Morales-Kent, a former Penn admissions officer and director of college counseling at the Thatcher School in Ojai, Calif. “People are selling a product, and in selling a product they’re putting a lot of pressure on people to make that product better. It’s more a reflection of the climate we’re in. And that’s a real shame.”

The Daily Pennsylvanian is an independent, student-run newspaper. Please consider making a donation to support the coverage that shapes the University. Your generosity ensures a future of strong journalism at Penn.

DonatePlease note All comments are eligible for publication in The Daily Pennsylvanian.